by Richard King

That John Martyn has died aged 60, not 28 or 74, seems entirely appropriate.

Ornery to the last he has left this life at a truculent age. Sixty is not really that old, there was still the lingering promise of something tantalising and remarkable yet within his grasp.

Had he died before he turned twenty-nine, Martyn would have left a recorded legacy as burnished as that of his friend Nick Drake, or as revered as Tim Buckley’s whose journeys into the soul baring snowstorms of libidinal folk-funk Martyn frequently out-peaked. As it was, Martyn’s record making was more often than not put on ice, re-booted and made over. The second half of his career took place at that sad stage door: the push and pull between record company and manager amiably slugging it out over the wayward talent.

The 80s and 90s nearly buried him. Grace & Danger was famously considered too harrowing by Chris Blackwell to release, though perhaps inevitably, it sold well. Thereafter the records were more about the angle, the crossover push: Piece by Piece featured the first ever CD single in the title track. Glasgow Walker and Church With One Bell were nice enough ideas on paper, both attempts at positioning him as the godfather of coffee table chill out, cover-versions, Portishead and all.

Meanwhile Martyn would annually take his turn through the theatres and civic halls; a one-man tsunami with a bandaged hand, midi’d up band and a breaking voice. Like the Fairports he knew a very British kind of road. Displaced by the punks as they were turning thirty, the Witchseason generation foresaw a career of six-week UK tours, happy to add frisson to the diaries of the newly mortgaged with their worries, their kids, their Red Stripe and their red seal. Defined, or is it cursed, as bearded evening music for Radio 2

But forget all that.

Let’s dwell instead in the amazing space of the peerless run of albums from Stormbringer to One World. Seven albums in seven years, no wonder he was fried. Two of the most underrated are Sunday’s Child and Inside Out. Both mix reels, lullabies and laments and channel them via Pharaoh Sanders, benign aggression and scat psychosis. In the midst of these aural gales lies Spencer The Rover, a trad arr. so finely judged and dew laden it proves Martyn was connected to something that had fallen all the way down the well, right to the very bottom.

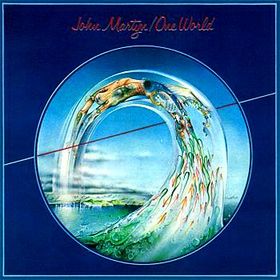

If you only know the smoker’s ambience of Solid Air, submerge yourself in One World, as aquatic, hot-flushed, leery and blissed out a disc as any ever sent to tape. The kind of sound Byrne & Eno might produce if they were the sort of men who regularly got into fights with drug dealers over women and money.

The tracks glisten in a thick, bacchanalian haze of sweet smoke and airy menace, it’s no wonder Lee Perry, an expert it’s fair to assume in such situations, turned up to the sessions.

But if you really want the sound of quick tempers, find if you can, the semi-bootleg Live at Leeds. Martyn formed a trio with Danny Thompson on double bass and England’s Elvin Jones, John Stevens, on singing hi-hats. They join Martyn’s echoplexed guitar and bad moon howling to make musical alchemy so loose, free and wild they make Can sound square. All three were, just as usual, self-confessed madmen at this point. What they cook up, in between filthy banter and on-stage horseplay, is music of the deepest, darkest most beautifully redemptive hue.

A geezer’s geezer, rough diamond, not exactly a saint….all the rest of it. Rehabilitaed by awards and on the verge of playing out a role as avuncular troubadour, people obviously wanted Martyn to see for himself how highly he was regarded. It’s hard to tell if he cared.

Listen instead to the beautiful mess he’s left behind. His was the real thing: Cosmic British music as elemental, star-crossed, abstract and deep rooted as anything produced on these imperfect shores.

Bless the weather.