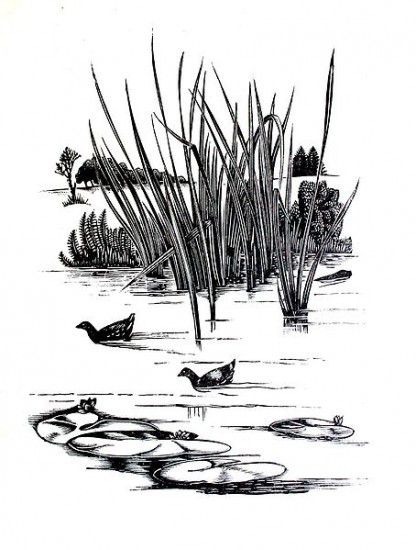

A year or so ago, when our book, ‘Caught by the River – A Collection of Words on Water‘, was at the design stage, thoughts turned to illustration. I had recently picked up a copy of ‘Sweet Thames Runs Softly‘ by Robert Gibbings (at the recommendation of Tom Fort in his book, ‘Downstream’) and I was knocked out by the engravings used within. ‘Look. This is what we need, something like this. In fact, could we not use these?‘. We did some research and were shocked that someone as talented (and once so famous) as Gibbings had fallen so far off of the radar but we bought up all the books we could find and realised that by taking something from each of them we had found exactly what we were looking for.

Our editor was Mathew Clayton, he made contact with Gibbings’ estate and a deal was struck. Here, Mathew puts Gibbings and his work into context.

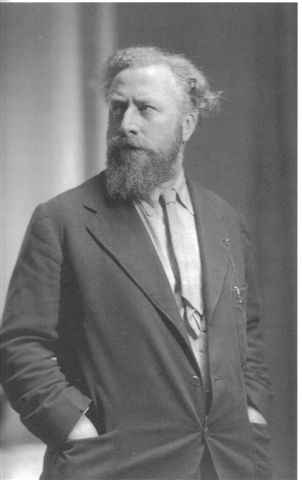

In July 1939, just before the start of the second world war, Robert Gibbings launched a flat bottom boat called Willow, that he had built in the workshops at Reading University where he worked, into the Thames. Over the next few weeks he meandered downstream. During the day he sketched the wildlife and enjoyed the hospitality of the many riverside pubs, at night he slept under canvas in the boat. The resulting book about this journey, Sweet Thames Runs Softly, the title taken from a 16th Century poem by Edward Spenser that is also quoted by TS Eliot in the Wasteland, was published by JM Dent in 1940, and became a bestseller. Its simple pastoral charm offered a picture of England that many feared we were about to lose. The book’s success catapulted Gibbings onto the public stage, he became one of the first natural history presenters on the BBC (David Attenborough has said he was an inspiration) and he wrote further bestselling books. By the time he died in 1958 Sweet Thames Runs Softly had been reprinted 11 times. Yet mention the name today and you are likely to be met with a blank stare. And whilst it is true his writing has not aged well the engravings that accompanied the prose still look wonderful; clear, simple, sharp evocations of the natural world and landscape.

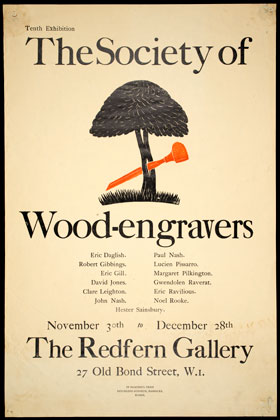

Gibbings was born in Cork, Ireland in 1889 but he moved to England to study art, first at the Slade and then at St Martin’s where Noel Rooke taught him wood engraving.  His expertise in this area led him in 1920 to help set up the Society of Wood Engravers. The society and its annual exhibitions provided a showcase for a whole generation of British artists people like Eric Gill, Philip Hagreen, David Jones, John and Paul Nash, Gwen Raverat and Eric Ravilious. The creative endeavours of this extraordinarily talented group were not limited to engraving; they designed bookplates, book covers, posters, logos, and typefaces, they wrote books and they published magazines. Influenced by the teachings of William Morris and his believe in the functionality of art, they didn’t feel that commercial design was beneath them. This down to earth approach to the business of being an artist was explained by Gill, ‘The artist is not a different kind of person, but every person is a different kind of artist’.

His expertise in this area led him in 1920 to help set up the Society of Wood Engravers. The society and its annual exhibitions provided a showcase for a whole generation of British artists people like Eric Gill, Philip Hagreen, David Jones, John and Paul Nash, Gwen Raverat and Eric Ravilious. The creative endeavours of this extraordinarily talented group were not limited to engraving; they designed bookplates, book covers, posters, logos, and typefaces, they wrote books and they published magazines. Influenced by the teachings of William Morris and his believe in the functionality of art, they didn’t feel that commercial design was beneath them. This down to earth approach to the business of being an artist was explained by Gill, ‘The artist is not a different kind of person, but every person is a different kind of artist’.

Whilst his writing bought Gibbings fame it is his work at the Golden Cockerel Press a small fine edition publisher, bought with borrowed money, that is seen as his artistic high water mark. In particular the edition of the Four Gospels that he published in collaboration with Eric Gill is considered by many to be the finest example of 20th Century private press bookmaking. With a print run of just 500 copies they sell today for over £10,000. His collaboration with Gill though was a little more intimate than most relationships in the publishing world. As Gill records in his diary on November 30, 1925, ‘Bath after supper and dancing (nude). R & M fucking one another after, M. holding me the while’ (R is Robert Gibbings, M is his wife Moira, the second M is Gill’s wife Mary). Gibbings was described by one of his friends as being, ‘a great nudist’ and much of the work at the Golden Cockerel was conducted without the encumbrance of clothes.

The Wall Street Crash in 1929 and the subsequent recession badly hit the fine edition book market and Gibbings was forced to sell the Golden Cockerel Press. This was a difficult period for Gibbings, his wife left him moving to South Africa with three of his children and at one point he was forced to live in a garden hut with his remaining son Patrick. He was not down for long though, he remarried and began travelling including two years living in Polynesia. In Bermuda he experimented with drawing underwater and the resulting book Blue Angels and Whales, published by Penguin, set him on the path that was to lead to Sweet Thames.

For many years Gibbings and his associates in the Society of Wood Engraving were out of fashion. Their preoccupation with the British landscape, the charm of their pictures, their reliance on craft, the importance they put on drawing and the line – even their unashamed engagement with the world of graphic design meant that people didn’t believe they were important. But frankly who gives a fuck what art critics think is important. Just take a look at Gwen Raverat’s pencil sketch of her dying husband Jaques – all of life is there – pain, love, comfort, hope and despair all encapsulated in a few pencil lines.

Just take a look at Gwen Raverat’s pencil sketch of her dying husband Jaques – all of life is there – pain, love, comfort, hope and despair all encapsulated in a few pencil lines.

In October 1957 his second book about the Thames was published, Till I End My Song, he died three months later in his cottage at Long Wittenham on the banks of the river he loved.