by Jon Berry

A quarter of a century has passed since the body of Richard Brautigan was found on the floor of a remote farm in California. Dental records were needed to positively identify him – the body had lain in late-summer heat for weeks, and no-one could be sure how long. It was an inglorious end, brought about by a solitary bullet, and announcements in the west-coast press were savagely indifferent.

Just another log-cabin demise, another long-forgotten hippy. Hardly newsworthy in the era that gave us Reaganomics and MTV.

Twenty-five years later, we are no closer to placing Richard Gary Brautigan (1935-1984) in anything like his deserved place, but his collected works are gradually appearing in reprints and limited runs and his spirit is there to be found in lo-fi Americana, if you look closely enough. Brautigan’s America is long-gone; poets and actors don’t gather in the desert to get drunk and fire shotguns at the night sky anymore, and the intricacies of men and women and their relationships – about which Brautigan wrote obtusely but brilliantly – are now articulated by the coffee-shop banality of Friends. In spite of this, or perhaps because of it, a return visit to Brautigan’s world is long overdue.

It was a fisherman who told me about Brautigan, and he did so with more than a sense of mischief. This fisherman knew of my weakness for American trout writers – frontier poet types like Gierach and McGuane – and suggested I pick up a copy of Trout Fishing In America, by some guy called Brautigan.

‘You’ll like him, he’s quirky’ said my friend, smiling.

When I found a copy – and that took some doing – I expected familiar big sky stories of Adams hatches on the Roaring Fork, road trips in battered pick-ups and men spitting tobacco and drinking camp coffee, bitching about ex-wives and duff leader knots.

Surreal tales of trout streams stored in sheds and water-borne semen floating downstream came somewhat as a surprise. My fisherman friend had one over on me, but I did enjoy the book, and decided to read a few more.

In the twenty-or-so years since I read Brautigan for the first time, I have occasionally wondered how many came to his writing thinking that Trout Fishing In America was an angling manual. Many more will have found him in recent years through Paxman’s mischievous inclusion of an extract from Trout Fishing… in his anthology, Fish, Fishing and the Meaning of Life.

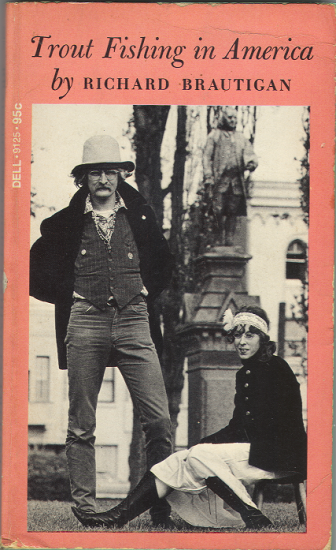

Those who discovered Brautigan first time around were, I suspect, the hippies and acid-heads of Haight-Ashbury, the undergraduates and their bearded lecturers, the disenfranchised and disenchanted. Brautigan’s 1967 novel may not have described how to drift an Adams, but it was an underground hit, credited with bridging the beat poets with the west-coast counter-culture. It launched a career that had, up to that point, been prolific but commercially unsuccessful. More novels followed, as well as collections of poetry and short stories, but by the ‘eighties he had become – to critics at least – an irrelevance, a reminder of long-haired whimsy ill-befitting the era of Gordon Gecko.

That era, too, is thankfully over. Brautigan can be read without the trappings of hipness or the burden of critical scorn – nobody really cares about dead hippies anymore, and so his words stand on merit alone. His novels, especially, reveal a unique and vulnerable voice. Surreal, autobiographical, whimsical and pithy – Brautigan could be all of them within a page. Moreover – like Dali, Zappa and Hitler – the man knew the power of a kick-ass moustache.

Newcomers to Brautigan might look first to the aforementioned Trout Fishing… and then, perhaps, Revenge of the Lawn. Treats like A Confederate General from Big Sur can come later. Those already familiar with his work may not know of the posthumous release of An Unfortunate Woman in 2000, a dark autobiographical novel written in the eighteen months before his death. It reveals a man no longer at ease with his own head – but the book reads beautifully all the same.

Another fishing friend – Ed the Rod-builder – gave me a final Brautigan book last month. It’s a biography penned by his daughter, Ianthe, and celebrates a flawed and troubled man who found peace only in words. Those words, beneath the trademark weirdness, tell of earth and sky and water, of the joys and perils of excess, of the logic to be found in absurdity, of the minute dramas in nature and ultimately of the fragile relationship between man and his world – the very stuff of CBTR.

He might just have enjoyed himself around here.