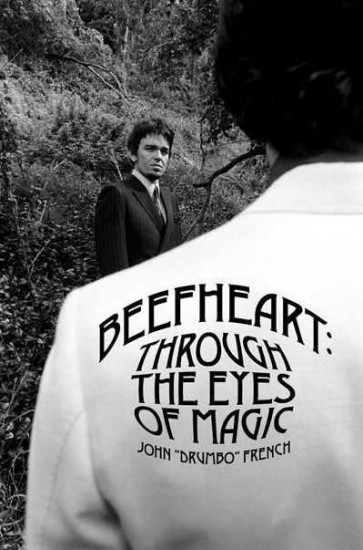

Captain Beefheart: Through The Eyes Of Magic – John ‘Drumbo’ French (Proper Music Publishing).

review by Jon Berry.

Sometime in the eighties I arrived at Canterbury University with a handful of modest A-Levels, a newly-pierced left ear and every intention of devoting the next three years to studying Modern Political History. Perhaps unwisely, I walked on to campus on that first afternoon wearing a T-shirt with Captain Beefheart’s face on it, and was accosted within minutes by a long-hair who pointed at me and laughed manically – ‘yeah, the Captain, excellent choice, come and get wasted…’

I was new and naïve and did as I was told. The music of Beefheart and the Magic Band was well-known to me, but the lysergic routes by which it had been conceived were not, until that unnaturally bright October afternoon. My interest in modern history survived the chemical onslaught, but I did learn a few other things of value that day – not least that Trout Mask Replica made no more sense than it had before, and that wearing a particular t-shirt could get a fresh-faced undergrad in to a whole heap of trouble.

I was saved from the long-hairs by the arrival of the Madchester sound later in my first year, but my love of Beefheart has survived to this day. And so, when this new biography arrived – all 860 pages of it, and written by the drummer who lasted longer than anyone else in Beefheart’s line-up – I was delighted. John ‘Drumbo’ French was the man behind the kit when Don Van Vliet created his finest albums, from Safe As Milk and Clear Spot to the seminal Trout Mask Replica, and few could claim to have been as close to Vliet during these lunatic times, or to have been so thoroughly exposed to the Captain’s quasi-cultist leadership of the group.

Through The Eyes Of Magic is not an easy read; previous work on Beefheart has tended towards hagiography, or has copped-out and adopted the ‘misunderstood genius’ line, but French has delved deeper, using extensive interviews with former bandmates and contemporaries as well as his own (admittedly faulty) memories to construct a first-hand, loosely chronological narrative. There’s clearly a great deal of resentment simmering in French’s words, and the author devotes considerable time to Beefheart’s tyrannical mind-games, and yet there is huge generosity here too; the author remains proud of the band’s work, impressed by the mind of the man who led them and well aware that Vliet’s behaviour might well have been seen differently by others at the time. There’s humour too – particularly when Zappa and Magic Band member Artie Tripp contributes. French’s track notes offer a thorough appendix, and a highly-personal account of the chaos in which each song was constructed.

French writes openly and freely, and ignores the established blueprints of rock biography. There’s repetition and some clunky editing to contend with, but this matters little and allows the book to flow with integrity – we get the unique perspective of the drummer in his own words, without any of the irritating fairy-dust of music journalism. French wisely avoids looking outside the group, or offering an interpretation of the sixties counter-culture beyond the claustrophobic world of the Magic Band; this is an insider’s view rather than a social history, and it is clear from the words of the contributors that Beefheart was their whole world at the time. The book’s format – extensive interviews with notes and recollections added by the author – takes some getting used to. But for the obsessive fan, this is no obstacle. If you can your head around Trout Mask, you can get it around anything. As a definitive account, I recommend it to all Beefheart fans – long-haired or otherwise.