by Robert St John

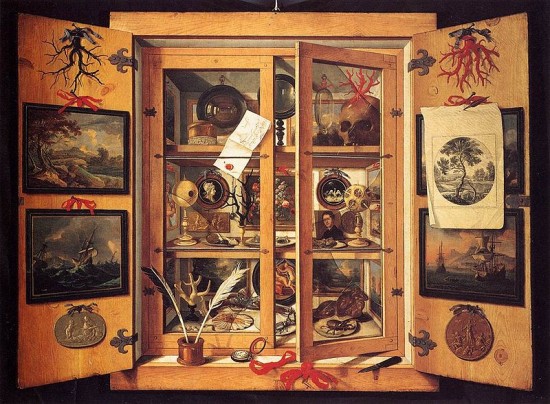

Often known as a Wunderkammer (literally, ‘wonder-room’), a Cabinet of Curiosities brings together a collection of unusual, obscure and exotic objects, trinkets and specimens. Popular in Renaissance Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, the cabinets reflected a thirst for intellectual stimulus and investigative spirit prompted by an increasingly expanding known world littered with new and exciting discoveries. Encompassing natural history, archaeology, art and antiquities; cabinets often included a miscellany of preserved animals, skeletons, minerals, shells, maps, sculptures, paintings and other unusual cultural objects.

The distinction between truth and myth was often blurred by the Cabinet’s curators – tales of mythical animals and phenomena were sometimes actively encouraged in order to captivate and challenge an audience. For example, Albertus Seba’s thesaurus “Cabinet of Natural Curiosities”, originally published between 1734 and 1765 (and recently reprinted by Taschen HERE) contains references to seven headed serpents, double headed deer and a “monstrous cat”. For many collectors, the value of a Cabinet of Curiosities lay in the ability to spark and stimulate conversation rather than imposing any set values or meanings on the (often disparate) collections.

The Cabinet of Curiosities concept persists in other ways. Britain has a rich amateur natural history tradition, and many people unconsciously collect, collate and compare their treasures from a day in the field. Windowsills, fireplaces and work-strewn desks become gradually festooned with feathers, leaves, pebbles and pinecones. Whether meaningful as curiosities, conversation starters, or simple reconnections to an outside world, many people inadvertently create their own modest Cabinets of Curiosities.

Similarly, vintage cultural and artistic aesthetics are being increasingly re-appropriated or re-imagined under the guise of new technology. The lo-fi light leaks and lens distortions inherent to lomography cameras are (relatively!) convincingly reproduced by iPhone apps. The analogue crackles, creaks and drones of a 1920s delta blues recording are a click away in any digital music recording software. Writing in British Wildlife (Vol 17: 1), Paul Jepson explored this theme to suggest that the digital photograph was “remastering” the Victorian practice of natural history. Digital “specimens” can be prepared, mounted and shared through online forums. The technologies are different, but the practice of field excursions, collection, preparation, sharing and discussion are remarkably similar.

In a sense, blogs may be seen as a modern analogue to the Cabinet of Curiosities concept – a repository for the interesting and the ephemeral to become encased in digital display. The blogger becomes the collector, the common thread tying together juxtaposed collections. For instance, Tumblr is becoming increasingly popular as a means for artists and musicians to tie together seemingly disparate influences, echoing Salman Rushdie’s metaphor in Midnight’s Children of stepping away from a cinema screen of jumbled, seemingly unrelated pixels to observe a complete picture.

Many organisations are thinking about how to reconnect the public with the natural world – see for example the National Trust’s Outdoor Nation project; the Our Rivers initiative and the iSpot national biodiversity survey. Working for BioFresh – an EU group concerned with freshwater biodiversity conservation – I am interested in finding new and imaginative ways to engage the public with nature.

Paul Jepson and I are currently exploring the potential to re-imagine and reinvigorate old concepts like the Cabinet of Curiosities through new technologies such as blogs, social media and smart phones to engage the general public. Crucially, the underlying ethos of the Cabinet concept is one of drawing individual conclusions and emotional responses to nature. The freedom and ease of use provided by digital technologies only enhances this openness and freedom of knowledge. These ideas are certainly ongoing (and being tested through our Cabinet of Freshwater Curiosities) but we hope that there is potential for them to spark a reinvigorated public engagement with the natural world.

Rob St.John is a researcher at Oxford University Centre for the Environment. He is co-ordinating the revival of a digital Cabinet of Curiosities to promote freshwater biodiversity conservation for BioFresh – an EU network of scientists. The Cabinet of Freshwater Curiosities can be found HERE.