by Will Burns.

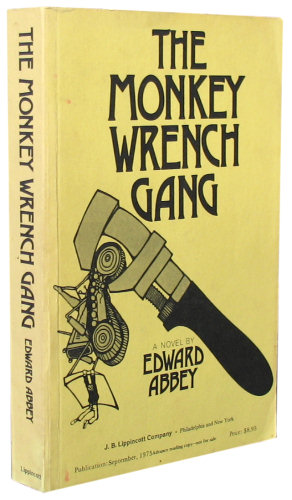

When I first read Edward Abbey’s Monkeywrench Gang, I had just returned from America and seen first hand the rivers, canyons, mountains and redwood forests that he yearned to protect with such force. These places were huge and genuinely wild, places that looked and felt ancient, foreboding, beautiful and dangerous and they seemed a world away from the woods and streams and pretty vistas of semi-rural Buckinghamshire that I had grown up with. Abbey’s story of a disparate group of outsiders’ increasingly daring sabotage attempts, starting with the destruction of earth moving equipment, and ending in a plot to destroy the Glen Canyon Dam, is as American in it’s emotional and philosophical scale as the landscape that is so deftly and sharply drawn within. Abbey was and remains a complex and difficult figure, especially measured within the context of a notional Green Left, which would remain the most logical inheritor of his mantle. A man hugely committed to conservation, an Anarchic liberal who also believed firmly in the American right to bear arms and the National Rifle Association, while also publishing essays betraying views on immigration (legal or otherwise) which present distinct difficulties to this writer, and have done likewise to a plethora of critics and fans since their first issue.

Abbey, however, prided himself on never shirking from a challenge or a difficult idea, and the apparent dichotomy of the quintessential liberal with a neo-conservative immigration agenda was always articulated with the power and clarity of thought (prevalent in all of Abbey’s work from Desert Solitaire onwards) which would lend his voice the authority and respect it undoubtedly still deserves. Take, for example, this from an essay entitled Immigration and Liberal Taboos that the New York Times refused to publish, “The conservatives love their (Mexican immigrants) cheap labor; the liberals love their cheap cause. (Neither group, you will notice, ever invites the immigrants to move into their homes. Not into their homes!)”

But the true legacy of Abbey’s novel, and his writings in general is the love, above all things, of the natural world. John Muir referred to it as “home”, for Thoreau it was the antagonistic muse and set stage, for Emerson a catalyst for his transcendental, burgeoning American poetry and for all four it was the landscape, the environment and their relationship with it, that yielded to them a unique and Great American literary voice (to a greater or lesser degree literary). This sensibility bled into Hart Crane, Wallace Stevens, Kerouac’s vision of the America seen from the Road, indeed becomes the trope of American literature and subsequently a relationship with absolute wilderness becomes central to the myth and idea of American-ness itself, expressed through it’s literature, Western films, paintings and photography.

____________________________________________________________

This year, the village is up in arms about the government’s plans to push through the proposed HS2 high-speed railway linking London To Birmingham. This will cut right across the Chiltern escarpment that encircles the village in which I live. Some of the most beautiful countryside in Britain, and for 25 years or so, all I ever knew of the wild. Mainly forested, highly managed conifer forests, this is where I first heard the dawn chorus, saw a goldcrest, treecreeper, sparrowhawk. Not exactly the golden eagles of Glen Canyon, and I’m sure as Abbey himself would surely have realized, the greater environmental good could well lie in less planes to Manchester and Liverpool, but when those diggers move in at the top of the hill and start cutting a swathe through my hillside, I’ll be getting the gang together. Go monkeywrenching.

Will and his band Treecreeper play the Caught by the River stage at the Port Eliot Festival on Friday 22nd July.