It’s more than likely a truism, but stuff that’s home-made increases tremendously in value the older you get.

Remember at school when you’d sneer at a home-made birthday card or, worse still, a hastily constructed present clearly completed by the donor’s fair hand? Heaven forbid actually being caught giving one to anyone else. The shame. The ridicule. Before then it was fine. You’d happily spend tens of minutes splattering glue and glitter badly over a piece of coloured rice paper as a toddler and present it as a masterpiece to the recipient, blissfully unaware of the impending stigma such actions would later have.

But then something changes. Possibly around about your mid thirties or maybe when you have kids. You begin to appreciate the time spent. The thought. The dedication. Of course, by this point you’re either actually so in love with your offspring you’d believe their snot, deftly arranged on a bit of card, was high art. Or what’s happening is the people making the homespun stuff are actually, at their current time of life, pretty handy at this nowadays. Experts, even.

Some months ago, I gained a glimpse into the world of what it’s like to be such a craftsman when I spent a day at the Kernel Brewery, grinning like an idiot and trying not to get in the way, all under the guise of research.

An unseasonably warm early April morning and I’d already donned green wellies and taken up the role of eager but really quite awkward so-called helper. I could feel the unease when I confessed to never having operated at the business end of a brewery before, but you can’t fault the guys for allowing an essentially enthusiastic bumbler to get his hands dirty making a beer, so hats off to them.

They put me to work, though. Weigh this. Pour that. Move that over there. Pick that up and pour it in here. Stop smelling the hops. Here, drink this. Before I knew it, lunchtime had arrived. A whole morning spent adding malts to hot water, sparging and tasting the wort. Which was like a soon-to-be-alcoholic Horlicks with buckets of sugar in it for good measure. In all honesty, the time passed like nothing as I drank in the learning and fed off the genuine love these guys have of what they do every day that produces some of the finest beer I’ve ever tasted.

The day’s particular recipe involved a few different malts and a variety of exotically named hops, none of which I’ve managed to remember. And as a coffee IPA, it also called for several kilos of the finest, high-grade ground Ethiopian, which was added liberally just after the boil.

Things seemed to be done haphazardly, but that’s a false impression you get when in the presence of the accomplished. You only need to sit down when they’re applying labels to bottles and witness the speed with which they’re casually labelling up a crate while you’re struggling to make them stick on remotely straight at barely half the rate to realise the gulf between amateur and professional.

But it’s the passion for what they do that allows them the casual nature. They’ve earned this nonchalance through years of painstaking practice and perseverance.

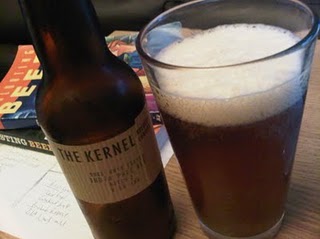

So some months later, I’m tasting the fruits of my labour. The second batch – the one being brewed when I pitched in – has been universally hailed as the best yet. I fear the part I played in its success was minimal; yet I still mistakenly refer to this as my beer. I’ve only one more left, which I’ve promised to another ale fan. All the rest have gone. Not only the ones I bought, but seemingly there are none left anywhere. It’s all been drunk.

All of a sudden, this beer I helped craft has become one of the most valuable commodities I’ve had the intense pleasure of creating. And subsequently helped make more scarce. I’m biased of course, just as I would be about my children’s creations no matter how primitive they may turn out to be.

But it is delicious.