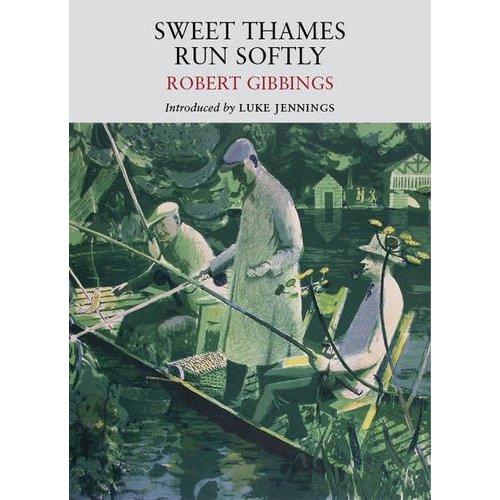

The introduction to the 2011 edition of Robert Gibbings 1940 classic, Sweet Thames Run Softly.

Written by Luke Jennings, for Little Toller Books.

When picking up Sweet Thames Run Softly, you might wonder if Robert Gibbings is your ideal companion. The river runs a considerable length, and you might consider that his didactic manner, and his schoolmasterly disquisitions on Ovid and Theophrastus, are more than a little creaky to the 21st century sensibility. Some of the book’s descriptive passages are fairly purple, like his description of a dream in which small creatures living in a country lane “all came to me and led me to their nests, drawing aside the sheltering roots and leaves that I might see into their homes”.

But Gibbings wins you over. His curiosity, his erudition, and his eye for arcane detail persuade you of the need to continue. He is the kind of man who carries a microscope in a punt, in case, moored in a backwater on a Saturday evening, he feels moved to examine sedimentary diatoms. “Some were crystal clear bordered with gold, some were sculptured like a cowrie-shell, others recalled the cuttle-fish ‘bone’ that we find on our shores”. Turning up a water-lily, he discovers “Aquatic caterpillars… as well as small trumpet-shells, and semi-transparent snails whose cat-like faces extruded as they marched along, seeking what they might devour”. This is science filtered through an artist’s eye, and the result is wonderfully strange.

Gibbings was born in Cork in 1889, and grew up in Kinsale, where his father was the rector. He studied medicine for three years before turning to art, eventually studying in London at the Central School and The Slade. During the First World War he served with the Royal Munster Fusiliers and was wounded in the neck at Gallipoli. Invalided home, he married Moira Pennefather, with whom he would have four children. To support his family Gibbings worked as an illustrator, much of the time for the Golden Cockerel Press, based in Berkshire, which produced limited-edition books. In 1924 he bought the Press, and for a time he and Moira enjoyed what would today be called an alternative lifestyle. Gibbings had rejected the devout Christianity of his father in favour of a form of sun-worship, and days of disciplined craft were followed by nights of hedonistic abandon, often in the company of Eric Gill, never a man to back away from sexual experimentation.

These lotus-eating days came to an end with the Wall Street Crash and the ensuing Depression. The market for privately produced books evaporated, and with it Gibbings’s funds. By 1934 The Cockerel Press had been sold, and Gibbings was living in a garden hut with his son Patrick, Moira having departed for South Africa with their other three children. Despite these diminished circumstances, Gibbings succeeded in wooing and winning Elisabeth Empson, a woman twenty years his junior, with whom he would have three further children. They married in 1937, and Blue Angels and Whales, a record of Gibbings’s undersea explorations in Bermuda, Tahiti and the Red Sea, was published the following year to some acclaim.

During the Second World War, Elisabeth and the children moved to Canada, while Gibbings taught book design at The University of Reading. He built himself a punt, the Willow, and as the RAF and the Luftwaffe engaged in lethal combat over the South Coast, floated down The Thames with his sketchpad and microscope. The result of these months of research was Sweet Thames Run Softly, published in 1941. It proved an immediate success, not least because many feared that the gentle world it portrayed was in danger of annhilation.

With only a pinch of irony he represents The Thames Valley as Arcadia, and himself as a kind of satyr, cheerfully and lustily pagan. Even a beech-leaf diverts him to erotic thoughts, as he notes how its “delicate downy growth” is comparable to that found in the small of a woman’s back. He tells the story of Pan and the nymph Syrinx and how “with the little goat legs hot on her trail” the nymph turns herself into a clump of weeds to escape the god’s attentions, and it’s not many pages before we discover Gibbings himself, tied up in a backwater, spying “a girl, running fast upstream, and she with nothing on”. He lures her aboard for a cup of tea but she is soon gone, slipping into the river like a naiad.

This identification of deep England with the unspoiled, harmonious wilderness of the ancients would have touched a sympathetic nerve in those troubled wartime days. Arcadia was originally an actual region of Greece, cut off from the outside world by mountains, and the name was used by the Roman poet Virgil and others to represent the notion of an isolated, and thus invulnerable, pastoral utopia. “It is those quiet mornings in August that remain in my memory…” Gibbings writes. “…those mornings when the sun rose through the mist like an ivory disk, seemingly without power to shed light or give heat, and those evenings too when darkness veiled the river, and time stood still, so that I seemed to be moving through events, past, present, and future, as if I was walking through a field of resting cattle”.

Descriptions like this will resonate with anyone who knows and loves the English countryside. He writes of “the hours soon after dawn when when, except for a herdsman… there would be no sign of life”. Even in the 1940s, the word “herdsman” would have seemed antique when applied to a Berkshire farm labourer, but its use is deliberate. In Greek, the word for herdsman is bukolos, and Gibbings is linking the scene to the “bucolic” works of Virgil and other classical poets.

Nazi Germany was not the only threat to the idyll. There was Progress. Giant beeches reduced to planking and transported to factories. In the Chilterns “…trees crash to the ground, three and four to the hour, and, on all sides, there is a wilderness of brown leaves, dead before their time.” Gibbings is enough of a realist to accept this state of affairs; the planking for his punt was once a tree, too. Of countryside “blemished by the marks of man” he suggests either passing through it at night or “mild inebriation”. These are very human reactions, and he soon cheers up. In Long Wittenham churchyard he finds yellow lichen, of which he gathers sufficient “to dye myself a fine purple tie”. He gives us precise instructions, ending with an admonition to wear the finished article “with a grey or blue shirt, and accept the subsequent admiration with humility”.

This is typical Gibbings in its balance of the droll, the eccentric and the scientifically precise, and it’s these characteristics which makes Sweet Thames Run Gently so readable. Its title is drawn from Spenser’s Prothalamion: “Sweete Themmes! Runne softly, till I end my song”, and the line would also provide the name of his last book, Till I End My Song (1957), about the village of Long Wittenham, on the banks of the upper Thames, where Gibbings died in 1958. He wrote of an age which seems distant to us now, and yet there is a sense in which a river is always of the present. Beneath the quiet surface of this account runs a strong, clear sense of life’s renewal.

Copies of Sweet Thames Run Softly are on sale from the Caught by the River shop, priced £10.00