An extract from 13 by Laura Barton

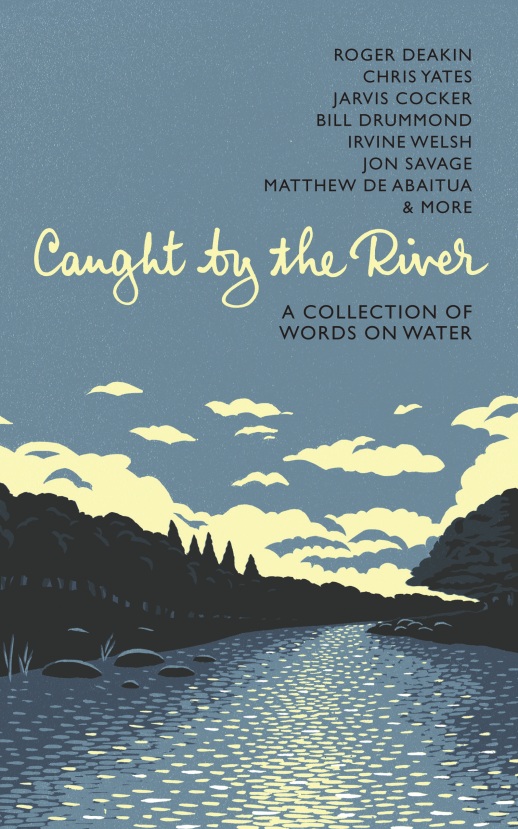

Taken from Caught by the River: A Collection of Words on Water

We grew up in thrall to the Leeds-Liverpool canal. One hundred and twenty-seven miles long, a spectacular feat of engineering, begun in 1770, and completed in 1816, at a cost of more than £1 million, it ferried coal, cotton, dust, ash, pigeon dung, rags, soap, bricks, lime and clay to-and-fro between Yorkshire and Lancashire. By the time I was born, it was barely still in active service, having retired into a destination for school trips and silent Sunday fishermen. It was here that we learned about sticklebacks and water boatmen, coots and moorhens, about coal barges and collieries, and all the things that made us Northern.

Amid it all, amid all the glory and the grandeur of the canal, we almost forgot about the River Douglas. The Douglas ran nearby, a tributary of the River Ribble, it covered thirty-five miles across the countryside and out to the sea, where, for its final ten miles, it is tidal. I think of the river now, viewed from a bridge near my childhood home: a small curve hurrying off towards the cabbage fields. Its banks grown wild with bind-weed and Indian balsam. I think back to its tributaries – Tarra Carr Gutter, Strine Brook, Centre Drain, Roaring Lum, The Sluice, Wham Ditch – names that feel rough and familiar to the tongue, like the morning roll-call at school, like the kick of vinegar and pea-wet at Gaskell’s chippy. They are words that carry me home, somehow, like the stations passed on the train back to Lancashire.

And when I think of the River Douglas now, it seems to represent to me the true spirit of the North, running a route that was not cleaved from the Earth, straight and man-made, but forged by nature’s own willfulness. And I think, too, of how her path is somehow mingled with the freedom and the wildness of my own youth, how her 35-mile territory matches the stomping ground of my own teenage years.

Up on Winter Hill she begins, on the West Pennine Moors, where the land is gorsy and windswept, and where the TV and radio masts stand. “Live from the tower of power on Winter Hill!”, the local radio jingle used to run, and, on cold days, you can only just make it out – a crisp white line against a hard, white sky. Such a strange, dark hill, a place of plane crashes and UFO sightings, murders, disappearances, electrical drones. From here on Winter Hill, fifteen hundred feet up, on a fine day you can see as far as Jodrell Bank and Blackpool Tower, to the Isle of Man, Snowdonia, Cumbria, the sea.

We used to drive up here when we were teenagers, just to look down across the county, to look out at all the streetlights and the roundabouts, at all the things we were desperate to flee. We went driving its looping roads with the windows down and the stereo up, the taste of brandy and wet air on our lips. We drove wildly and too fast, drove with no particular destination, and though we never thought of it then, I like to think of us driving the same course as the Douglas – broken free, now, from the Ribble, as if our path were somehow divined by the river running along beside us.