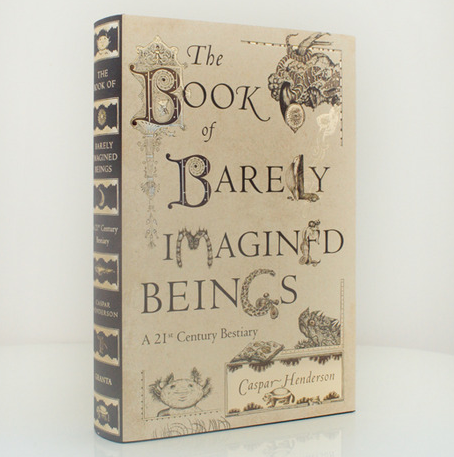

Caspar Henderson – The Book Of Barely Imagined Beings (Granta hardback)

Review by Roy Wilkinson

Interested in hearing about farting walruses, or the dolphin orgies known as ‘wuzzles’? Keen, in principle, to be introduced to a 17-year-old Filipino crack-shot called Stalin, a young man expert at shooting the fig-eating golden-capped fruit bat, all the better for the restaurant menus of Manila? How about something on Hentai, the sub-sect of Japanese porn in which a woman is sometimes depicted in a bath full of eels? Or, indeed, what about an aside on such eel species as the black sorcerer, the rusty spaghetti eel and the abyssal cutthroat eel – an aside that leads on to Moby-Dick, DH Lawrence and the Tsar Bomba, the largest thermonuclear device ever detonated? If you’re thinking ‘yes’ to any of the above, this exhilarating A-Z animal-kingdom overview is probably for you.

Caspar Henderson’s The Book Of Barely Imagined Beings is a kind of rationalist, scientific spin on the the crazed bestiaries that captivated the Middle Ages – the gilded feasts of calligraphy and nut-job free-interpretation where a pelican might rip open its breast to bring its young to life with its own blood, thus becoming a living representation of the Lord Jesu. As Stalin and the spaghetti eel might indicate, Henderson is unafraid of digression. This is a book that digresses to a spectacular, informative and inspirational extent. Such is the book’s heady and charming animal-cerebral charge that the author has felt emboldened to create a new term for his work – an ‘aletheiagoria’, a combination of phantasmagoria and ‘aletheia’, the Greek for truth and revelation.

This reporter must confess he’d never previously heard of Caspar Henderson. He has, it seems, led an interesting life. Wikipedia says Henderson has worked on film scripts in Los Angeles and as an aid worker In Uganda. More recently he’s written on “science, [the] environment and human rights”, for publications including the FT and New Scientist. Even more recently Henderson has worked at two websites, openDemocracy.net and Chinadialogue.net, both think-tank-style forums for global-political discourse. Chinadialogue is a non-profit, Anglo-Mandarin set-up, designed to lobby on environmental issues amid China’s industrial expansion. It doesn’t seem like a bad way to pass your time, a useful use of your lifetime. The Book Of Barely Imagined Beings seems like another work of a lifetime – or at least decades’ worth of accumulated wonder, insight and intrigue. The is the first long-form work from Henderson that could be described as aimed at the ‘general reader’. But how general remains to be seen.

At first glance the book’s stylised, retro packaging – sepia tones and antique type styles – might see it confused with something like Conn and Hal Iggulden’s The Dangerous Book for Boys, the 2006 soaraway publishing smash where lads and dads were encouraged to enter a portal to the past – back to a place where they could build go-karts from Victorian prams or cook fresh-caught fish over a glowing bed of genuine child-picked charcoal. But, not to worry, it’s difficult to imagine a publisher as dignified as Granta going for the publishing equivalent of the latest must-have keep-calm-and-carry-on camping accessory – maybe the Cath Kidston kiddies’ cattle-prod in cosy kidskin carry-case. The Dangerous Book for Boys and The Book Of Barely Imagined Beings both variously make for appreciated Christmas present, but Henderson seems suited to a much more particular audience.

Barely Imagined Beings does take the form of an A-Z compendium, but it’s an A-Z where A is the axolotl and X is the xenoglaux. Other chapter subjects include the quetzalcoatlus, the Japanese macaque and the unicorn (or at least Henderson’s chosen monoceros stand-in – the goblin shark, a horn-nosed denizen of the ocean depths).

Once you’re in among this book’s brilliant web of thought-provoking detail, then an additional bonus might suggest itself – selecting some suitably weird organisms that Henderson has ignored. Personally, I felt myself stifling a excited exclamation of ‘Where’s the desman?’ (Despite a lifetime of intermittent reading about animal life it wasn’t until five years ago that I first came across this creature, a kind of Hoover-nosed aquatic mole, restricted to two geographic tribes, one in Russia, the other in the Pyrenees). But there are good reasons why Henderson’s chosen D is the dolphin rather than the desman. The chapter specimens have been compiled carefully – fascinating in their own right but also leading into wider topics. The dolphins take us to thoughts on non-human linguistics and non-human conceptualisation. The xenoglaux is in fact Xenoglaux loweryi, the long-whiskered owlet, a tiny owl of Andean rain forests. It’s an owl that here becomes a jumping-off point for fascinating and persuasively non-didactic counsel on climate change and extinction.

Among the things introduced on the back of the long-whiskered owlet is ‘occult precipitation’, a term applied to ecosystems that actively abstract water from the ambient atmosphere. This book is full of things like occult precipitation. These pages seemingly draw on a mass of reading. But there’s something very likeable about the catholic nature of the book’s bibliography – one that lists a hugely populist book like Bill Bryson’s A Short History of Nearly Everything alongside a scientific paper like ‘Fossil steroids record the appearance of Demospongiae during the Cryogenian period’.

This book is a work of huge synthesis, an extensive and enlightening gleaning far and wide. We live in an era when the internet often seems like some electro-etheric, information-OD version of the Pacific Trash Vortex, the continent-scale mass of plastic and sludge out on the oceans. Maybe because of this, books like Barely Imagined Beings are becoming increasingly common and increasingly useful. But let’s leave things with a couple of examples of the astonishing stuff that Henderson has separated from the trash.

Familiar with the ‘humanzee’? This was a Soviet attempt to breed a human-chimp hybrid, first by attempting to inseminate female chimps with human sperm, then by seeking out a male chimp who might impregnate a female Russian volunteer. Or, on a less unpleasant note, how much do you know about the quincunx, the X-shaped array of five spots that thinkers from WG Sebald to the 17th-century physician Thomas Browne have remarked upon, locating it everywhere from sea urchins to pine trees to the Egyptian pyramids. With such Amazing Factology becoming part of Henderson’s resplendent larger creation, The Book Of Barely Imagined Beings becomes, at the very least, one of 2012’s most remarkable books on the natural world.

The Book of Barely Imagined Beings is on sale in the Caught by the River shop, priced £20.