The Pattern Under the Plough by George Ewart Evans

Illustration & cover artwork by David Gentleman

(Little Toller, 256 pages with flaps. Out now)

Introduction by Patrick Barkham

My East Anglia was a land without horses when I was growing up in the 1980s, twenty years after George Ewart Evans wrote The Pattern Under the Plough. Vast fields of barley and sugar beet were tended by blue and red tractors that had obliterated the animals and their handlers, who spoke so eloquently to Evans of a vanishing age. If I had looked, and listened, more carefully, however, I might have detected small and overlooked signs of what this Welshman discovered when he moved his family to the village of Blaxhall in Suffolk to write novels shortly after the Second World War.

Pattern takes its name from the aerial photographs that reveal traces of ancient settlements, even after the soil has been ploughed for centuries. If we search hard enough, argues Evans, the remnants of beliefs and customs linked to rural traditions that persisted for centuries before being swept away in the nineteenth century also reveal themselves. These old ways of thinking have sunk into the subsoil, as Evans would have it. I like to think of them floating, like untethered ghosts, through our lives today.

My favourite ghost is the cult of the horse – and the nightmare. East Anglia has long been defined by the arable farming so suited to its soil and climate. In his adopted homeland, Evans discovered that there were many more beliefs and customs – a more neutral phrase he preferred to the judgemental ‘superstitions’ – linked to harvesting corn than to domestic animals such as cattle, which are far more powerfully symbolic in old Celtic societies in the west, where pasture is predominant. The exception in the east, however, is the horse. In Suffolk, the horse superseded the ox and was harnessed to the plough as early as the twelfth century. Farms were horsepowered until the twentieth century, when we swept aside 800 equine years in the space of a couple of decades.

As Evans explains in Pattern, horses were venerated in northern Europe until late medieval times. Odin, the most powerful of the Norse gods, rode a grey eight-legged beast called Sleipnir, who galloped between the earth and the World of Death. A dream featuring a horse was a dreaded premonition, and this idea of the horse as a harbinger of death became mixed up with its symbolic associations with the pagan Mother Goddess, who existed in many guises – Diana, Hecate, Maia, Hecuba, Artemis, the Great Mother – long after Christianity became the official religion in Britain. The horse was sacred to this White Goddess, a medium through which she could be reached, a symbol of fertility, and a potent sacrificial animal.

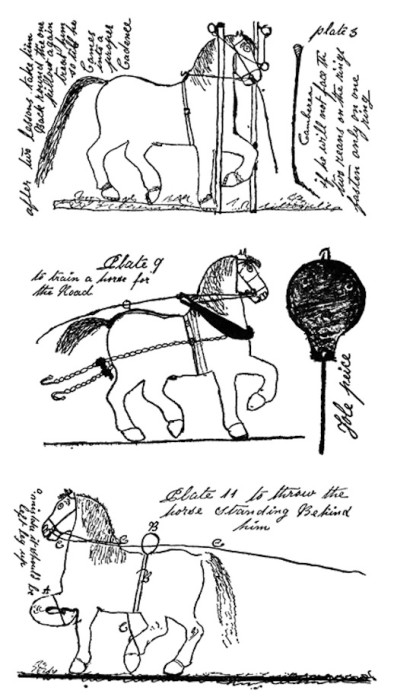

In the countryside, when a farmer found his mare unaccountably upset and sweating after a night in the stables, he believed it had been ridden by spirits. This was the original Night Mare. The only people who understood how to calm and control these important, highly-strung animals were horsemen, ‘the big men on the farm’ and ‘a whispering lot’ as 88-year-old farmer John Grout told Ronald Blythe in Akenfield, like Pattern, another acclaimed 1960s account of East Anglia’s disappearing rural world. During his two decades living in Suffolk and another two in Norfolk, Evans became fascinated with horse magic and ‘jading’ and ‘drawing’ in particular. Jading was the horseman’s ability to make his charge suddenly stand still as if it was paralysed; drawing was when the horse obediently came when it was called. This God-like power to control a rather highly-strung animal was revered and feared, and men were inducted into the kingdom of the horse with devilish sounding rituals, whereby they acquired a frog or toad bone gathered in an obscure way involving moonlight and secret burials. This set horsemen apart from their community although the secret to their control of horses was mostly prosaic: their jading and drawing potions were concoctions of herbs and oils that triggered a horse’s extremely acute sense of smell. It just looked like magic to the rest of us.

The Pattern Under the Plough is a rich trove of such secrets, flinty reminders of what we have forgotten. It is a journey into society’s subconscious, a lost world that resurfaces in echoes and splinters, in sayings and objects we are blind to the meaning of but keep on our mantelpieces.

Thanks to Evans, a ghost of our horsey past materialised recently when I visited a house where the resident had fashioned a lovely wind chime from flints with holes in them, which were threaded through a string. These flints were once called hag stones and hung outside barns to protect horses from nightmarish rides by hobgoblins. The hole represents a pupil and the stone is an All-Seeing Eye, a potent device for warding off evil all around the world.

I have another forgotten symbol on my hearth at home: a fossil of a sea-urchin. It was simply a pretty decoration until Evans informed me it was once known as a fairy-loaf in Suffolk and was typically placed on mantelpieces to ensure there was always bread in the house. A piece of ‘imitative magic’, its beautiful domed shape encouraged the bread to rise. ‘This is the usual course of old discarded images and dogmas,’ wrote Evans. ‘They sink into society’s unconscious, the old traditional and unbroken rural culture; or they are kept alive in the games and practices of children.’

The story of how a grocer’s son from a mining town, one of thirteen children, an athletic, rugby-loving Welshman came to be a pioneer of oral history appears to be as haphazard as many fragments of our lost beliefs and customs. George Ewart Evans’ parents ran a grocer’s shop in Abercynon, south Wales, but because his father gave credit to workers from the village colliery, the business eventually became bankrupt – although when the shop was taken over by the Co-operative his father stayed on as manager.

Evans himself hoped to be a writer but, unemployed in the Great Depression, he retrained as a PE teacher and got a job at an experimental community school in Cambridgeshire founded by Henry Morris, who hoped to arrest the decline of village life. Here, Evans met his wife, Ellen, also a teacher. After the war, they took their four young children to Blaxhall where, unusually for the era, Ellen became the breadwinner – headmistress of the village school – and Evans was the house husband, still fervently pursuing his thwarted ambition to write novels.

Becoming increasingly deaf, Evans had to make a conscious effort to overcome his isolation at home and get out and meet his neighbours. Whilst helping organise village celebrations for the 1951 Festival of Britain, he was struck by how local people enjoyed talking about the past. He was fascinated by the stories he heard, the way they were told and the language used, which he had only come across in sixteenth and seventeenth century poetry. Rather than struggling with his novels, he realised there was a compelling subject before his very ears. The older residents of his village had witnessed a transformation in farming life and, more profoundly, a revolution in the way people thought.

During the 1950s, Evans began listening, and taking notes. Later he borrowed tape-recorders from friends at the BBC and recorded his conversations, which became radio broadcasts. In 1956, he sent a manuscript to Faber and Faber. ‘For the past eight years I have been living in the above village which is in a remote part of Suffolk; and I have been struck by the number of interesting survivals here,’ he wrote. His manuscript was given short shrift by one of the publisher’s readers, who called it ‘revoltingly pompous and pedantic’. But Morley Kennerley, an American director of Faber, disagreed. ‘This book is a joy,’ he noted on the manuscript. ‘Most readable, nothing patronising or ye olde about it and the author’s treatment just right.’ Faber went on to publish nearly a dozen books for Evans.

With Ellen, Evans later moved to Needham Market, in Suffolk, and then to Norfolk, and his listening became known as oral history, his fierce commitment to creating a true picture of society through the quiet voices of ordinary people informed by his communist politics. Writers such as Evans and Ronald Blythe became hugely popular in the 1960s and 70s as awareness grew of the destruction of village life and the social and cultural as well as environmental losses caused by the industrialisation of agriculture. But mainstream academics were less than impressed with these literary works. ‘Old men drooling about their youth’ is A.J.P. Taylor’s famous dismissal of oral history. Historians suspected it was inaccurate, and earnest, educated outsiders such as Evans were probably spun some tall stories by mischievous locals; East Anglians have a notoriously dry sense of humour. More damningly, oral history was seen as nostalgic, romantic and, in the case of Evans, preoccupied with men’s work at the exclusion of women.

Today, the folklore found in The Pattern Under the Plough might be dismissed as picturesque, irrelevant trivia from the past. Why is it unlucky to marry in May? Why were walnut shells packed between the joists of old houses in Suffolk? How can wild pigs forecast gales? What links a yule log with the return of the word ‘backlog’ from America? Why are country people reluctant to use their front doors? Pattern has the answers and yet it is not a compendium of laughably archaic quirks.

If yesterday’s beliefs seem irrelevant, consider the role of the horse today. It is a creature of leisure, not work, and yet one which continues to play a strange and powerful role in our society. The survival of a ‘horsey’ upper class – ‘a ruling minority whose riding on a horse gave them in every sense a claim to a higher station,’ as Evans puts it – is probably because of our ancient horse cult. The importance of horses in Britain and Ireland gave rise to horse racing, which flourished in the sixteenth century and remained an almost exclusively British and Irish sport for three centuries. The irrational taboo against eating horse that endures so strongly today is also a notable product of the horse’s symbolic position in our past.

Stripped of their historical context, many old beliefs do sound ludicrous and colourful: a fried mouse is a cure for whooping cough; passing a baby through a spliced ash sapling at sunrise will cure it of epilepsy – provided the ash sapling heals too. As a magnificently unjudgemental guide, Evans shows how these ‘superstitions’ had their own internal logic and significance in the era to which they belong. Before mechanisation of farming and the great social changes wrought by the First World War ‘men themselves still thought in the same traditional or primitive way: there were forces outside their control that had to be placated; their hold on life was uncertain; they lived closer to nature and they knew what nature’s dominance could mean: fair crops and plenty one year, poor harvests and subsequent famine the next. Murrain and pestilence fell upon them as though out of a clear sky and compelled them to use the small resources of knowledge, however misconceived, that they had at their disposal.’

Some of these resources still make sense within the value system of the Enlightenment and contemporary science. Mould from a hot-cross bun used as a cure for a festering wound was once dismissed as magic; since the discovery of penicillin, however, this ancient practice has rather more credibility. Another ‘magical’ medicine still deployed in Evans’ day was the curing of warts. He visited dozens of villages in East Anglia and almost every one had a wart-charmer, a kind of rural witch doctor, whose secretive counting of warts and mumbled spells over the patient almost always succeeded. It sounds nonsensical but Evans believes it held a pertinent lesson for modern medicine: the charmer’s treatment was directed not so much at the disease itself but at the patient. ‘All the hocus-pocus was an instinctive attempt to stimulate the patient’s own healing force,’ he writes. Traditional healing was not successful with the infectious diseases that modern medicine so brilliantly combats but Evans argues that modern medicine’s specialisation and skills tend to treat the patient as a depersonalised ‘case’, ignoring ‘an important therapeutic factor – the force within the patient himself that can greatly help his own recovery’.

In Pattern, Evans does not simply seek to show where ancient beliefs still make sense by the standards of today. He seriously challenges the way we think about the past and the way we believe we think now. On the one hand, he warns against our ‘tendency to read our own enlightenment (dare we say it?) into the minds of people who had been conditioned by an entirely different, less tamed and less predictable, environment.’ On the other, he provides powerful arguments against the modern assumption that we are superior scientific beings with a monopoly on wisdom and rationality.

Evans’ search for society’s subconscious is also a rebuke to safe, conventional history – more concerned with accuracy than truth, he argues – and academic specialisation that has seen historians, archeologists, linguists, sociologists and anthropologists ploughing their own narrow furrows in libraries or societies remote from their own people. Evans wanted writers and scholars to conduct historical anthropology in their own country. ‘There is just as rich a harvest to be gathered in the so-called civilised countries of the west as in parts of Asia, Africa or the South Seas which are still the anthropologist’s natural habitat,’ he writes.

Almost fifty years on, many of the points he made in Pattern have been heeded: history does not simply begin half a century ago and plenty of anthropology looks into developed countries as well as out to the developing world. And yet it would be worth listening again to some of the lessons learned by Evans’ oral history. The related cults of individualism and celebrity that so grip modern life encourage us to regard the unfolding of history in terms of the actions of glamorous or powerful individuals, and we still too frequently neglect the quiet voices of ordinary people who typify social change and the way we think.

Do we ever really change the way we think? Evans was in no doubt that almost all the old, irrational beliefs had been scorned and jettisoned, even if many customs would be transmitted through time and exist ‘in a thinner, more abstract form’ in the future. But he argues that hope and desire are still stronger than reason and we must guard against assuming that ‘having got rid of these irrational beliefs, we have therefore basically altered our own cast of mind.’ Writing two decades after the war, Nazism was, for Evans, a powerful example of a deep irrationality in modern life, and all the more destructive for being harnessed to industrial technology. We may chortle at the idea that a dead mouse can cure whooping cough but future generations may look back on our embrace of nuclear weapons, our rude and lawless behaviour in virtual worlds or our relentless exploitation of the environment with a similar mirth. This inability to act in the long-term interests of the human race is an obvious example of how often we continue to depart from purely rational thought. The light shone on our own minds by The Pattern Under the Plough is what makes it so fascinating, humbling and essential.

Patrick Barkham, Norwich, 2013

The Pattern Under The Plough is on sale in the Caught by the River shop, priced £10.

Patrick Barkham will be joining us at this year’s Port Eliot festival, his latest book, Badgerlands,is published by Granta and out now.