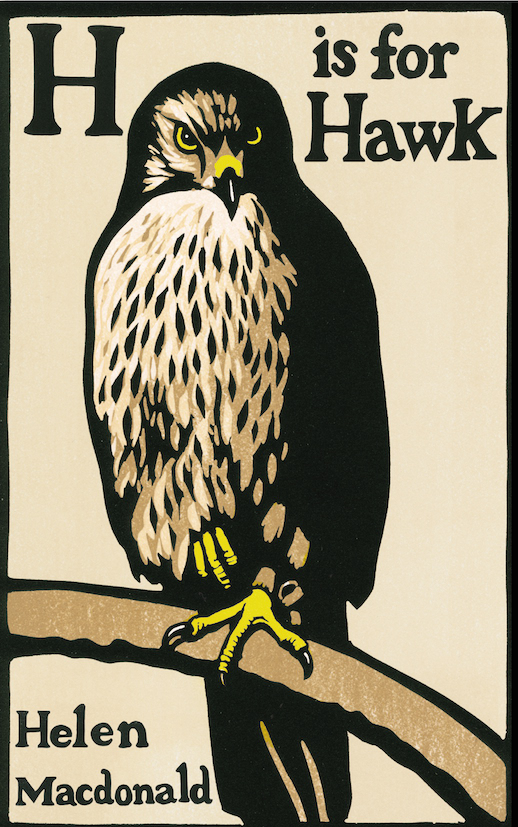

Interleaving memoir, nature writing and biography, H Is For Hawk is a uniquely luminous account of Cambridge historian and falconer Helen Macdonald’s training of a goshawk, undertaken in the wake of her father’s sudden death. It’s also an account of The Sword In The Stone author T.H. White’s heartbreaking and misguided battle with his own hawk, which he described in his lesser-known book The Goshawk (1951). Melissa Harrison caught up with Helen to find out how H Is For Hawk came to be.

You’ve loved birds of prey since you were a child. Why?

Because I thought they were the most perfect, beautiful things the world had ever made. To be honest, I still do. In Barry Hines’ novel A Kestrel for a Knave [dramatised by Ken Loach as Kes], Billy Casper says that when they fly “everything seems to go dead quiet” – which gets across how hawks can instill something like a dim, religious awe, and have done for thousands of years across myriad cultures. Maybe part of my love for them is caught up in that history. But the role of birds of prey in recent literature and film is also revealing. Both Casper’s kestrel and TH White’s goshawk are the consorts of unhappy souls, as is Richie Tenenbaum’s saker falcon, Mordecai, in The Royal Tenenbaums. These are hawks as tutelary spirits for the lost or dispossessed. My goshawk Mabel was too, after my father died. I’ve begun to suspect that my own early obsession with raptors may have been related, somehow, to the loss of my twin brother just after he was born.

Could you describe for us the process of realising that you were going to write this book? How did it feel to begin?

Even as I trained the hawk I wondered if I ought to write about what was happening – compose dispatches from the front lines of grief. Living with the hawk was fascinating, all-absorbing, wild and often very beautiful, but bereavement and self-imposed isolation took me to some very dark places indeed. It took me seven years to get enough emotional distance for the book to be written at all.

You mention in the book that you kept a journal while you were training your goshawk, Mabel, and that you drew on it to write the book. How detailed was the journal – or did the ins and outs of training her all come flooding back as you began to write?

I kept two journals: one in falconers’ shorthand, listing the date, weather, the hawk’s condition, flights, quarry, and so on. The other was a more emotional diary about far more than just the hawk. I referred to both while writing the book, but they were less important than I’d assumed. Grief did something strange to my powers of recall, made memories crystal-clear. That season with the hawk is still bright in my mind. I can’t remember what I did last week, but I can remember exactly what it was like to sit with Mabel under a woodland yew in a winter rainstorm, watching her feathers grow dark with water, even down to the coldness of raindrops on my scalp and the shapes of leaves under my feet. It’s very, very strange.

H Is For Hawk is suffused with loss, but it is also suffused with love. Were you aware, when you were writing it, of the love – or only of the loss?

Both! Because love and loss are so close. What’s that line? ‘Grief is just love with nowhere to go’. The love in the book is grief for my father, love for the hawk and the landscape and everything in it, and also sorrow and compassion for T.H. White. The awareness of mortality I felt that year inflected everything. Sometimes it made me see darkness where there was none. But it brought also a new sense of the preciousness and precariousness of lives both animal and human.

T.H. White is a fascinating figure, a deeply complex and troubled man with whose book, The Goshawk, you clearly have a problematic relationship. How did you manage to get under his skin in the way that you have? The psychological insights in the book are so subtle and compassionate.

Thank you! Yes, I hated The Goshawk as a child, felt I understood the hawk in the book far better than White. One of the themes of H Is For Hawk is the lure of attempting to put oneself in other minds — be they hawks or long-dead writers. And it’s also about learning to love things that are nothing like you. It was very hard to get under White’s skin. But the more I found out about his life the sorrier I felt for him. Despite his literary and financial success, his life was such a sad one. He’d had a terrible, violent, abusive childhood and lived at a time when his sexuality was reviled. To get to know him I read Sylvia Townsend Warner’s magisterial biography, and all his letters, unpublished notebooks, journals and manuscripts. The journals in particular helped me to feel my way into White’s life. They are strangely like a child’s scrapbooks, packed with terrible drawings, tipped-in feathers and polaroid photographs; the written entries course with self-justification and all the insecurities of the alcoholic. There’s a lot of bombast, a lot of self-hate, and so much loneliness. The loneliness was deeply affecting. Reading his journals made me feel he was one of the loneliest men that has ever lived.

For those of us with no experience of raptors, one of the great joys of the book is the way you describe Mabel: her moods and expressions, the subtleties of her body language and behaviour. We’re used to such affectionate portrayals of dogs and cats, but birds of prey can seem, to outsiders, remote and hard to read. Did you set out to demystify, to win readers round and help them love hawks as you do?

We see hawks mostly as symbols of wildness, ferocity and rarity. That obscures their living reality. They’re not that remote or hard to read –they’re simply unfamiliar. To fix this all you need to do is watch them very closely for extended periods of time. I came across a marvellous account of this process in F.B. Kirkman’s book on studying black-headed gull colonies in the 1930s. At first he was bored senseless, experiencing ‘tedious intervals of many minutes, seeing nothing of interest and marvelling at the folly that had brought me there’. But the longer he looked the more he saw, and eventually he found it hard to find the time to take notes at all. Everything the gulls did became meaningful. That’s the secret to understanding any animal’s behaviour: sitting and watching with an open mind. I’d love it if my book helped people to see hawks as complicated, loveable, fascinating animals, not just distant manifestations of human concepts.

You’re an artist, a poet, a historian and a falconer as well as a writer. It feels to me as though H Is For Hawk drew on all those skills. Would you agree?

This question baffled me for a while. Training hawks isn’t much like writing a poem or painting—but then I thought about it carefully and decided that maybe in a way it is. In all of them you have to invest yourself in something and work with it until you relinquish all control over it. That moment is deeply satisfying. The point when a picture is finished, when you can’t do any more to it or it will spoil. Or when a poem you’re revising clicks, fits together, and locks you out. In falconry you put all of your heart and hard-won skills into training the hawk, then cast it from your fist to fly free. Then all you can do is stand and watch, and wonder.

There are people who feel that, with the possible exception of endangered species, birds should not be kept in captivity at all. What would you say to them?

Some animals certainly shouldn’t be kept in captivity: orcas, for example, and I’ve just read an incredibly distressing article about the history of zoos medicating depressed bears and great apes. But not all animals are orcas or apes, and there are other ways of keeping animals than putting them in cages. Wild hawks spend most of their time loafing, preening, bathing and snoozing, interspersed by bouts of active free flying and hunting. That’s what falconry birds do too. Also, hawks are mostly solitary birds: I suspect it’s less cruel to keep a single hawk than a single rabbit in a hutch, or a horse alone in a field. All the hawks used in British falconry are captive-bred, and have been for generations. But there are wider cultural issues here. We’re increasingly enforcing the boundaries between humans and wild animals: there are very few opportunities these days to interact closely with them at all. I think this impoverishes human lives. And it also makes animals small and far away, so we don’t care about them as deeply. It’s hard to love something and fight to protect it if you’ve only ever read about it or seen it on a screen. One of my great heroes is the American falconer and wildlife biologist Fran Hamerstrom. She believed that to really appreciate wild animals people should be allowed to experience them first hand, as she had as a child; animal-keeping drove her to become a fiercely committed conservationist. She saw such relationships as fostering wonder and responsibility towards the natural world. Wonder and responsibility are the watchwords here. Of all the ways in which people are still able to interact closely with essentially wild animals, falconry is, I think, as enlightened as it gets.

This is a very personal book, and a very brave one. How do you feel about having put so much of yourself on the page?

The only way I could write about grief was to be brutally honest about how it felt. I’m definitely nervous, now, about having put it all out there, but there wasn’t any other way to do it; when I tried to dissemble or hold back, the words wouldn’t come. But I’m not quite the person in the book any more, which makes it feel less exposing. I was so deep in grief back then I saw the world very differently. For example, all I could see in J.A. Baker’s The Peregrine at that time was a desperate desire for death and extinction, a hopelessness I found chilling. I read it again recently and that isn’t how it seems at all.

The combination of nature writing and memoir seems to be a fruitful one, with Richard Kerridge’s book about amphibians, Cold Blood, and Kate Norbury’s forthcoming memoir The Fish Ladder two other notable examples. Why do you think that is?

Back in the day, most books about nature were written in that expert tone I loved as a child. It was the voice of the grown-up, the voice that knew all the facts. It explained, enumerated, was occasionally lyrical, rarely if ever admitted ambivalence or ignorance. It never pointed out that our own lives and cultures shape that the way we see nature. The new nature-memoirists are doing what anthropologists learned to do years ago. Their books are reflexive: they interrogate the expert eye, try to uncover the grounds of our attachments to the natural world. And more soberly, what drives these memoirs is also a kind of witnessing – books written by nature-obsessed children who grew up to remember the things that are gone. It’s one thing to read that there are fewer wood warblers now than thirty years ago, but it is a different thing to read how it feels to sense their absence in a wood that was once a place made of wood warblers as well as trees in your mind. Communicating the pain of losses like that can’t be done with statistics.

Can you talk a bit more about nature writing – what have you enjoyed recently? Where do you think the genre (if it is one) is heading today?

Tim Dee’s Four Fields and Richard Kerridge’s Cold Blood are recent favourites. Both are lyrical works by superb natural historians, both brim-full of love and emotional honesty. As for where nature writing is heading—I hope that it gets a little angrier, to be honest. I’d like to see more books filled with beauty and fury and desperate hope, not simply distanced beauty and elegiac despair.

You touch on the idea of ‘chalk-cult mysticism’ in the book. Many Caught by the River readers will be chalk stream fans; can you expand on this a little?

I use the term loosely to refer to a strand of English mythical history that has seen chalk landscapes as magical places of communion with an imagined past. This sort of historical consciousness has frequently involved a presumption that love for the landscape rests on ancestry, history, and blood ties – often leading to the very troubling assumption that other traditions, other ways of living and loving and thinking have less right to the land than you do. David Matless’s Landscape and Englishness and Patrick Wright’s books, particularly The Village that Died for England, which interrogates the chalk-cults of interwar Britain, are essential reads for anyone interested in the relation between landscape and national identity. And I’m just reading Kitty Hauser’s excellent Bloody Old Britain, which beautifully discusses interwar connections between chalk landscapes, politics, archeology and the visual imagination. As for chalk streams proper: there’s one near me, rising from the foot of chalk hills at Fowlmere, a gin-clear foot-deep stream full of finger-sized brown trout; it’s magical. I go there whenever I can.

Birds of prey are doing relatively well in Britain at the moment, but there are some serious problems. What are you most worried about? What needs to change?

Raptors are still being poisoned and shot. The strongholds of British goshawks are forestry plantations: when young birds leave those sanctuaries they tend to ‘disappear.’ Hen harriers are on the brink of extinction in England for the same reason, and eagles and kites suffer too. These are the sad casualties of very old wars about who owns the countryside, who has the right to define what it is, how to use it, what is valuable in it. We desperately need to halt the persecution. And yes, some birds of prey are indeed doing very well in Britain today: red kites and peregrines for example; but I worry that the return of these visible, charismatic raptors masks insidious and invisible losses of less charismatic birds affected by modern land-use methods: turtle doves, corn buntings, grey partridges, lapwings, linnets…

The book ends just as you find a new house and Mabel goes into moult. What has happened since?

Mabel flew for many more seasons then went up to a breeding project in Cheshire, where she was flown in the autumn and winter by a very expert falconer. While in an aviary last year she died suddenly of the horrible fungal infection aspergillosis – an airborne killer that strikes out of nowhere and that’s been the bane of austringers for centuries. The man who flew her was devastated, and so was I; she was an extraordinary hawk, and much mourned by those who knew her. I’m considering taking up a new hawk next year. But not a goshawk. There’ll never be another hawk like Mabel.

H is for Hawk is published by Jonathan Cape on 7 August. Copies are available to pre-order from the Caught by the River shop here at the special price of £12.00