Marcus O’Dair talks to the musician, landscape artist and author Richard Skelton on the eve of his short UK tour:

He’s tried playing with a bark plectrum, burying a violin in the soil, placing balsam leaves in the sound hole of his mandolin. He has even tried bowing barbed wire fences, although the sound produced apparently leaves plenty to be desired. Many composers have been inspired by specific places, but Richard Skelton does more than merely reflect. Instead, his music is often created with the land itself, a fact reflected in its presentation (early releases came with birch twigs or alder catkins included in the packaging) and track titles such as Bark, Xylem. Skelton has released more than 20 albums, as well as visual and literary work, but the title of his upcoming concert series encapsulates his whole oeuvre: Landscape.

Skelton has released music under various names over the years: Heidika, Carousell, Harlassen, Clouwbeck, *AR, A Broken Consort, Riftmusic, even plain Richard Skelton. The concerts coincide with the release of his second album as Inward Circles. And, having made music inspired by his previous homes in Lancashire and Ireland, the album in part reflects his new home in the Furness hills of Cumbria.

‘The landscape is much more elemental, in my experience, than either moorland Lancashire or coastal Ireland,’ he explains. ‘There’s a particular microclimate here – a consequence of the altitude, orientation and proximity to the sea – which means that it’s rarely ever still. There are strange, quick-moving mists, frequent rain-showers and an almost viscous light at dusk. It can rain so much that the fields are frequently waterlogged, and the myriad becks and rills on the fell-sides turn white with foam.’

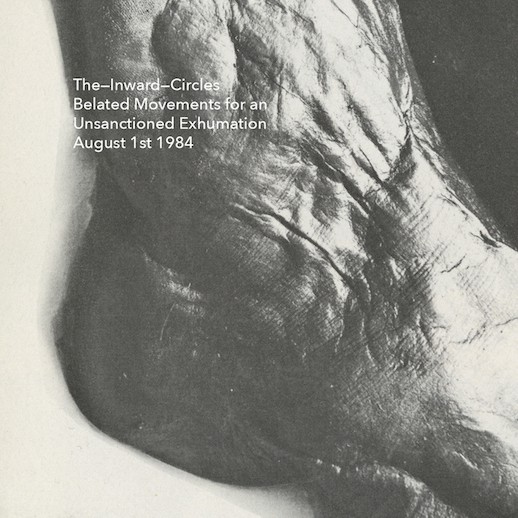

Skelton’s new album is entitled Belated Movements for an Unsanctioned Exhumation August 1st 1984. It is a reference to Lindow Man, the 2,000-year-old man discovered in a peat bog near Cheshire in the 1980s. There’s a clear subterranean theme running through the record: Skelton also quotes lines by the American poet Ronald Johnson about making ‘new windings with the mole’. Is it too literal to link the rotting of peat bodies with his own music-making process, in which a violin, say, will be buried in the soil?

‘I think it’s highly possible that I made a subconscious connection between violin burials and bog bodies,’ he replies. ‘When I first began bestowing objects in the ground, some ten years ago, it didn’t have such funereal connotations; the metaphor I would use is one of sowing. It was one of a number of strategies that I employed in order to involve the materials of my work in the land itself: an embodied approach to composition.’

Yet Skelton describes himself as ambivalent about this ‘embodied approach’, realising that, repeated too many times, burying instruments could become a gimmick: ‘The work should stand on its own, regardless of context,’ he insists. ‘With compositional methods that are too direct, the work risks becoming a novelty, where the process becomes the focus, rather than the work itself.’

Skelton no longer includes twigs and catkins in his releases, not only because the process is unsustainable as his audience grows but also because, as he himself says, there’s something contradictory about an artist who draws inspiration from the landscape then taking from that landscape in order to augment his recordings. He recalls one particular occasion when, commissioned to compose work on the theme of extraction, he buried a violin for such a long period that he rendered it unplayable in the ordinary sense. ‘On one level,’ he says, ‘ it seemed an unduly violent fate to visit upon an instrument.’

‘Certainly,’ he continues, ‘the act of extracting sounds from its body felt, in many respects, like performing a kind of autopsy; an interrogation of the dead. Nevertheless, I reminded myself that decay is a natural, necessary – even beautiful – process; that the soil contains agencies that effect transformation, renewal and growth, and that music could be perceived as a symbol of that regenerative power.’

Skelton did not ‘prepare’ a new instrument specifically for Belated Movements: it would have been too much, he suggests, to inter a violin in Lindow Moss. Yet the album does feature sounds from the disinterred violin, and the theme of decay remains strong: natural, necessary, beautiful, and with an undertow of violence. Were the sounds more ‘treated’ than on Skelton’s previous releases?

‘Yes,’ he replies. ‘I recorded an entire album with acoustic instruments. But I wanted to take it further – for the music to decay, for its bones to decalcify and dissolve, so I metaphorically bottled it in peat-water and left it to stand. The first track on the album, Petition for Reinterment, is 28 minutes long, and it undergoes quite a transformation. Crucially, I wanted the entire album to have “teeth”, particularly as the last track is concerned with the bones of bear, lynx and wolf, so there’s an unprecedented amount of digital distortion throughout the record.’

The results are epic, elemental: to listen to Belated Movements is to feel humbled by forces unimaginably strong, as after being half-drowned by a relatively small wave. Although it moves slowly, the music feels inarguable, inexorable, like the shifting of a tectonic plate. Skelton has expressed his interest in a line by Gerald Manley Hopkins: ‘nature in all her parcels and faculties gaped and fell apart’. I ask whether that image links back to the sense of decay that characterises Belated Movements – and possibly all his work in music and beyond.

‘With regard to Belated Movements,’ Skelton replies, ‘it certainly is centred upon pedological processes, but, as previously mentioned, decay is transformative, even if it appears destructive. The record ends with a sustained, violent upsurge – a call to the once indigenous predators of the British Isles to “awake, arise, reclaim”. This may seem fanciful, but in the context of geological epochs – of the cycles of glaciation and interglaciation – there is ample time and opportunity for such a shift in the ecology of our islands.’

Given that a Skelton concert is a relatively rare occurrence, I conclude by asking what we can expect from the three Landscape shows: ‘It will be a auditory inhumation,’ he replies. ‘We will begin with a collective symbolic descent into the soil, to the fox’s “earth beneath earth”, from where we’ll summon “Canis, Lynx, Ursus” and return, with great violence, to the surface.’

20 March 2015 – Manchester, Islington Mill

21 March 2015 – Bexhill on Sea, De La Warr Pavillion

22 March 2015 – London, St John on Bethnal Green

Marcus O’Dair will be discussing his book, Different Every Time: The Authorised Biography of Robert Wyatt on the Caught by the River stage at this years Port Eliot Festival. Copies of the book are on sale in our shop, priced £15.