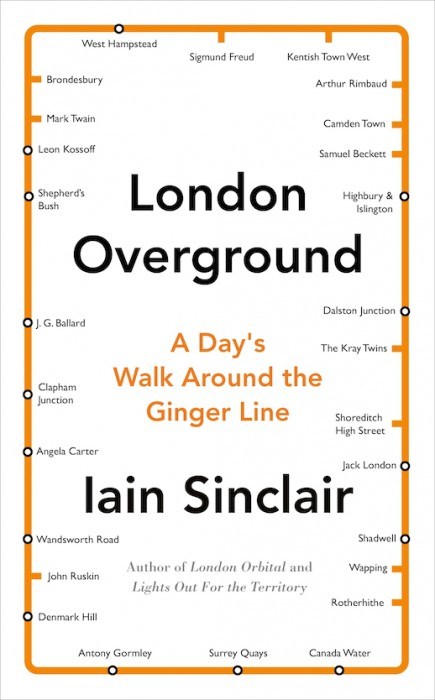

An extract from London Overground: A Day’s Walk around the Ginger Line

by Iain Sinclair

Hamish Hamilton, hardback. Out now

Battersea Bridge confirms the distance now separating us from the Overground circuit. Shallow arches, alternately black and white, harpoon directly into the alien aggregation of the Chelsea Harbour development. Our footfall bridge is a Turkish fantasy, nicely managed, playing games with scale, under thunderous skies already stained with sunset. We are conscious that the five-span bridge with its seductive cast-iron detailing, its rose-pattern screens throwing shadows on the path, is a relative newcomer, a Joseph Bazalgette replacement of 1885, taking trade from the original ferry. Coming over by boat allowed time for adjustment. There are claims that this was the point of the Thames, then sluggish and fordable, where Julius Caesar made his crossing in 54 BC.

Alongside the statue of Whistler, in a little riverside alcove, is a bench of respite, where pilgrims can follow the exiled artist’s unblinking stare back across the Thames to St Mary’s in Battersea. A gaunt figure, in a greasy trilby, was slumped, panting, recovering, legs gone. I noticed that he was wearing a shroud-like garment, a hospital gown or unlaced straightjacket, under his long brown coat. Andrew was too tired to bother with memorials. The American impressionist, master of tone, moonlight on river, silver on luminous black, left him cold. He was flinching from the sudden wealth of Cheyne Walk, the compulsory blue and brown heritage plaques like posh people’s satellite dishes. He spoke of cycling down here, not really knowing where he was, and making deliveries to pioneer production companies. He didn’t have the puff, at that moment, for his usual interrogation.

‘Four miles to Mortlake,’ said the man on the bench, ‘Must be at least that, wouldn’t you say?’

He spoke as if he knew me. The trick is never to stop moving. Just smile and nod. I nodded.

‘You could get the Overground from Imperial Wharf to Clapham Junction, then the train,’ I said.

‘I don’t employ buses. Or trains,’ he replied. ‘One never knows who one is going to have to sit beside.’ He gave Kötting a meaningful glare.

The distressed walker reminded me of a character out of Sebald, a revenant squeezed from the sepia juices of old photo albums, incubated out of friable press cuttings, translated and mistranslated into the contemporary world. He called up the Sebald laboratory assistant in Manchester, the one who absorbed so much silver that he became a ‘kind of photographic plate’. Face and hands, exposed to bright light, turned blue. Then other selves, earlier portraits, came up through his skin: a carousel of death masks.

Sebald, I was reminded when I came to check that reference in The Emigrants, also had something to say about the dangers of a morbid obsession with train systems. Which sometimes led in his manipulated histories to acts of ruitualized suicide, head on tracks, spectacles laid aside, shadowy form approaching as a terrible sound:

mortality. ‘Railways had always meant a great deal to him,’ Sebald wrote, ‘perhaps he felt they were headed for death.’

Our man hunched forward. If he moved, the pain would be unbearable. His brown brogues were unlaced; in fact, they had no laces.

‘It hurts too much to bend down.’

He had no socks and his ankles were like wrists, all knob and hairless bone.

‘How far have you come?’

‘Brompton.’

Long walks, at certain points, throw up messengers from parallel worlds. You see them when you need them. Perhaps, in some strange way, they need us too: confirming absence, confirming the validity of a confession that has to be made, over and again. I’ve come across old women supposedly picking up litter in Kentish woods who saved me miles by putting me back on the right path. Wise men waiting in birdwatchers’ hides near Whitstable. Snake-tattooed stoners on narrowboats with keys to forbidden locks.

Kötting took the chance to massage his own ankles, but he wouldn’t risk removing boots that were beginning to slurp with burst blisters and the cheesy secretions of feet that had never quite recovered from the rats and mud of his swan voyage up the Medway.

The vagrant’s story emerged in fits and starts. The Mortlake room, in a house overlooking the graveyard where Sir Richard Burton, the saturnine adventurer and eroticist, pitched his stone tent sepulchre, was the motivation for this desperate hike. The man without socks lived between river and railway. The light of one. The sound of the other. He wasn’t well, but who is? Blinding headaches, white light. Pressure on the basal ganglia. Eventual collapse. Local quack. Ambulance with siren screaming. Hospital on the wrong side. Brain tumour. Power drill splits the scalp.

‘They always say “size of a grapefruit”. More like a moderate-sized lemon. And good riddance.’

He discharged himself in two days, against advice. And is now walking back to his Mortlake room, his papers.

I told him about a person who sent me a bag of notes, diagrams, X-rays. He superimposed the outline of his tumour, the size of a Christmas pudding, on Clerkenwell. The notion being to walk the shape as a healing pilgrimage. He dedicated the exercise to Rahere, the monk who founded the hospital of St Bartholomew in Smithfield. He died within a month of the attempt. I left out that part of it. And we took our leave, wishing the outpatient well.

It’s unfeeling and predatory to dwell on such incidents, but the encounter with the man on the bench gave our steps a certain lift, as we discussed and debated the veracity of his account. The wounded walker didn’t remove his trilby when we raised our hands in a farewell salute, but I saw no evidence of hair beneath.

Heritaged artists of former times, now approved as enhancers of real estate, dominated this stretch of the river. Along with parking space for superior houseboats under threat of eviction, to make room for the yachts of oligarchs. Here were moorings where bohemians hung out in swinging London films of the 1960s. John Osborne, at the time of his triumph with Look Back in Anger, was tied up at Chiswick. In more recent times, Damien Hirst customized one of these floating islands to the highest specifications. He was part of a co-operative of barge owners trying to buy the Chelsea Reach moorings, before the owners could sell the land for £4.75 million. The Cheyne Walk spectres of Sir Thomas Moore and Sir Michael Jagger nudged us towards the Overground. We would all live on the river if we could, waiting for the rains of Schadenfreude to wash us away. Climate is another word for conscience.

Turner, Whistler, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, George Eliot, Mrs Gaskell, Hilaire Belloc, Philip Wilson Steer, Sylvia Pankhurst, Ian Fleming: quite a party. What a roost of entitled egos blue-badging enviable properties.

London Overground is on sale in the Caught by the River shop, priced £14

Iain Sinclair will be discussing London Overground with Luke Turner, editor of on-line music and culture magazine The Quietus, at a Caught by the River event at Rough Trade East on Tuesday 21 July. Admission is free, details are here.