Back in the early ‘90s, just after I’d moved to London, my dad came to town to see a Richard Long retrospective at the Hayward Gallery. Being an impoverished student, I figured if I tagged along, I might get a free lunch or at the very least a few pints out of it. At that point, my mind was very much one track, that track more than likely being some demented acid house record that probably even the person who made it can’t actually quite remember now (possibly it was me? Who knows) Anyways, greedily hanging in there, I happily let my dad pay for the exhibition and strolled in behind him, high hats fizzing away in my otherwise vacant brain, quite unready to be educated in the ways of Richard Long and ‘land art’.

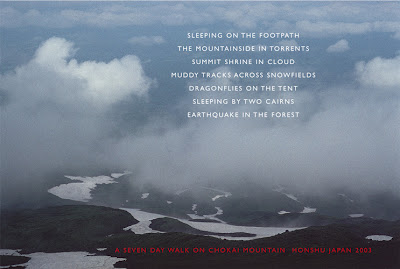

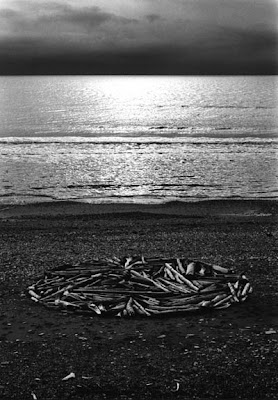

Pretty much immediately, Long’s art had an effect on my impressionable brain that was, looking back, startlingly powerful. His immense photographic work, where the only signs of human contact are patterns drawn in rocks or sand or mud by the artist himself, appeared to me like primeval landscapes – not like the kind in films where buxom cavewomen run around chased by plasticine dinosaurs, more like the kind where nothing moved, where centuries could pass and the scenery would peacefully exist unchanged, like the surface of the moon just before the first Apollo craft broke the silence. The text works on the walls struck even more of a chord – words in lists, sequences of events; descriptions of walks across different countries, walks through different eco-systems, through mood swings; from deep wilderness to log fires in isolated pubs then onwards. The words danced off the walls like poetry, so simple, so stark, so evocative of the places they described. Unadorned black and white type (Gill Sans, if you’re interested), sometimes long lists of events, sometimes just the basic distances and places, others just sparse sentences as minimal as a haiku – they each became Technicolor in the imagination. His sculpture works took natural materials from points on his travels such as slate or elephant dung and made vast geometric patterns out of them. Pictures on walls made up of hundreds of prints from hands covered in river mud, somehow both precise and childlike at once.

From that point onwards, I’ve followed Long’s work. I’d go to exhibitions and I’d pause for thought under vast text pieces. As odd as it seems, as an impoverished student and then someone perpetually bound up with life in the city (afraid to leave in case I went away then missed something epoch making), Long’s artwork often acted as a springboard to daydream my way out of my environs for a few minutes, much like a good book or film or a piece tucked away in the travel section of the newspaper. Being brought up in the countryside in Wales, the landscapes and the materials used are familiar, hardwired into me like programming.

In terms of recent art, of exhibiting in similar spaces and both being Turner Prize winners, Long’s artwork really is something like the polar opposite of Damien Hirst’s – Long is pensive, lonely and meditative while Hirst is brash, fabulous and show-offy. Hirst’s diamond encrusted skull is as subtle as a David LaChappelle produced Elton John gig. Long is more like the acoustic solo artist playing from below a fringe at the 12 Bar Club, who knocks you sideways with beautiful soul music while you’re ordering your third pint of Strongbow.

In the last couple of years, outside of galleries and exhibition programmes, I’ve been reminded of the subtle nature of Richard Long’s work through the writings of some of my favourite authors, both through coincidence or design. Bill Drummond’s peerless book of essays, ‘45’, and the lesser read but equally brilliant follow up “How To Be An Artist” talk of his acquisition and subsequent destruction of a Long piece. In the books, Drummond buys a photograph by Long, named ‘A Smell Of Sulphur In The Wind’, then an existential crisis about the ownership of art that sees him chopping the picture up into 20,000 equally sized pieces. He then goes about trying to sell each piece by placing adverts on road signs the length of the motorways of the UK (my girlfriend bought me one of them on eBay for Christmas last year, meaning I now own a Richard Long, albeit one not much bigger than a match). Parallels can also be seen in Iain Sinclair’s psychogeographical voyages round London on foot, specifically “Lights Out For The Territory” & “London Orbital”, books which undertake journeys mapping the urban landscape, the grime and bustle of our capital, in flowing, lyrical prose, much like the solitary walks described in Long’s text work – here, London’s side streets are rendered in the same mental colours as those seen on passages across Dartmoor or rural Ireland.

This month sees the publication of Robert Macfarlane’s brilliant book “The Wild Places”. The book is a hugely thought-provoking travelogue around the few places in the British Isles unspoilt by ‘human progress’. Like in Long’s artworks, Macfarlane’s voyages in the book are more often than not solo missions, lonely endurance tests to document the natural world at this point in time, before climate change, that thoroughly modern mighty re-arranger, shifts all the pieces without our permission. At one point, Macfarlane talks about the history of cartography, about how in the past, prior to modern day grid mapping, people’s journeys would be governed by “story maps (which) represent a place as it is perceived by an individual or by a culture moving through it.” Macfarlane’s use of story mapping is the narrative backbone of a compelling and masterful book. In many ways, the same principal provides the spine of Richard Long’s artworks – “if we follow in Long’s footsteps, then we will physically experience his sculpture” (from www.doubledialogues.com).

Both Macfarlane’s book and Long’s art seem utterly timeless, out of time even; one giant step removed from the modern world and all its mundane hang-ups. These are journeys to be undertaken without an iPod, without an Oyster card,without mobile phone reception. Whether you or I ever undertake such journeys remains our choice – but the fact that Richard Long and his fellow observers, cartographers & psychogeographers are out there, mapping out the peripheries so that we can bask in them and daydream, that does come as a huge reassurance to me.

Robin Turner

Richard Long’s exhibition, ‘Walking and Marking’ is on at the Scottish National Gallery Of Modern Art in Edinburgh until October 21st