Post war New York City, and the sound hurtling from the cellars of Manhattan’s mid-town jazz clubs is the frantic sound of bebop. In this smacky, predominantly black milieu with its own language and code of conduct, one white guy is attracting attention from those in the know. His name is Gil Evans.

Evans was the guy that Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Gerry Mulligan and any great jazz musician wanted to hang with. Some dropped by just because they could shoot up or store their works in his sparse 55th Street basement apartment, but most came because he was the ultimate music man, turning them on to whatever he was into at the time – Stravinksy, Bartok, Debussy, George Russell, whatever. He was the hipster, the don, the searcher for the “mystical thing” and – as he sat at his desk scrutinising scores that he’d borrowed that day from the New York City Public library – everyone wanted to know what his take on the new thing was.

Fast forward over a decade to 1960, and Evans’ name had escaped that 55th Street clique. Largely because of his beautiful, symphonic work with Miles Davis (Birth Of The Cool, Miles Ahead, Sketches Of Spain) his uniquely panoramic take on music had penetrated deep into the public realm. Along the way he’d also made a few intriguing records of his own – ‘New Bottle, Out Wine’ in particular – but that November he was finally about to enter the studio to deliver his very own masterpiece – a record called ‘Out Of The Cool’.

There are a million and one great things about this record. In fact, you can probably listen to it for a lifetime without unravelling all of its subtleties and secrets. That’s because first and foremost, it’s a wonderfully arranged and beautifully executed suite of exceptionally ambitious head music. The players on it are great – drummer Elvin Jones from the classic Coltrane quartet, bassist Ron Carter, Jimmy Knepper on trombone – and the atmosphere right from the outset is one of controlled mod cool (the opener ‘La Nevada’ is a 15 minute epic, all hissing rhythms and protruding horns).

Still, while ‘Out Of The Cool’ manages to combine some of Evans’ toughest arrangements – the aforementioned ‘La Nevada’, Horace Silver’s ‘Sister Sadie’ – with some of his most devastating ballads – ‘Sunken Treasure’, ‘Bilbao Song’, at its core is one track that just elevates it into another stratosphere altogether. ‘Where Flamingos Fly’ is the album’s centrepiece and one of the greatest pieces of music ever recorded. Built around a trombone line so heavily melancholic that once you’ve heard it, you’ll never, ever forget it, it curls its way around you over five magical minutes.

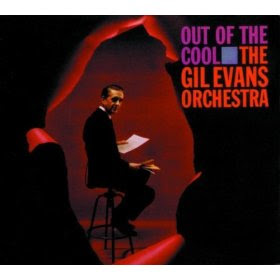

When it was released, it was billed under the Gil Evans Orchestra and released on the great jazz label – Impulse! The sleeve features a black-suited Evans looking more academic than ever. Unfortunately for Evans, the record didn’t register in the minds of the public on release, lost in the squawking militancy of the avant-garde and remains a hidden gem to this day. A genius record from a genius man, it’s an album that when you get it, you can’t imagine anyone in the world not wanting to hear it.

James Oldham