Edgar Holloway who died this week was last surviving artist who was part of the etching revival of the 20s and 30s.

On my 15th birthday in 1983, Edgar (who was my godfather) gave me one of his prints. ‘Rainy day in Scotland’ does what it says on the tin. The picture is dominated by an empty road leading towards an ominous mountain. Day is turning to night, storm clouds gather above and it looks like it has been pissing down for weeks. It’s simple bittersweet melancholy struck a chord with my teenage heart and it has been hanging on my wall ever since. Each time i look at it i wish i was trudging down that road getting soaked.

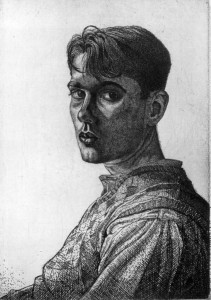

Edgar was born just outside Doncaster in 1914 the son of a miner turned printmaker and picture framer. His talent for drawing showed itself at an early age. By 10 he was making lino prints, by 15 he had acquired his first etching press and by 20 his work had been purchased by the British Museum, the V&A and a number of other national collections.

He attended art classes only sporadically and was largely self taught. He learned to etch by reading ‘The Art of Etching’ a 1924 book by Ernest Lumsden. The process requires considerable patience and skill, lines are scratched onto a wax covered piece of metal this is then dipped in acid which bites into the exposed areas. Ink is rolled onto the plate and the resulting image is pressed onto paper. Popularised by Rembrandt in the 18th century it enjoyed a resurgence in the first few decades of the 20th century as an affordable alternative to buying paintings.

But tastes changed. Modernism took hold and etching with its emphasis on draughtsmanship, craft and technique began to fall out of fashion. By the end of the 30s Edgar was finding it difficult to make a living solely as a printmaker so he branched out into teaching, signwriting and even painting ice cream vans.

In 1949 he was invited by the wood engraver Philip Hagreen to move to Ditchling Common in Sussex and become a member of the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic. Founded by Eric Gill and inspired by GK Chesterton’s long forgotten idea of Distributionism, the Guild was a quietly radical community of Catholic craftsman attempting to create, ‘a cell of good living’ in the countryside. They shared workshops, built their own houses and held communal events like the annual sports day. Edgar, now married and with children, was made a full member in 1951.

For most of the next two decades he earned a living as a letterer and

illustrator, drawing maps and designing dust jackets for London publishers. Concentrating on commercial work was a financial decision but one that chimed with Eric Gill’s philosophy that, ‘there is no more to art than honest craftsmanship’. Yet at the end of the 60s, with all his children grown up, he turned back to etching and for the last 40 years has been adding to the body of work he began in his teens. The Guild was wound up in 1988 but he carried on living in Woodbarton one of the houses they built on Ditchling Common right up until his death. For the last years of his life, helped by his second wife Jennifer, exhibitions of his work were shown all round the country.

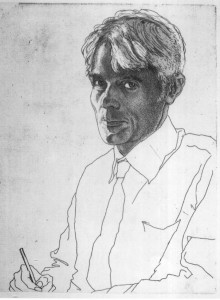

He drew mainly landscapes and portraits including around 30 self portraits which mark his voyage from adolescence to old age. I have one hanging over my fireplace that was produced in the 1930s, around the time that he produced the original watercolour that ‘Rainy day in Scotland’ was based on. It is typical, in many ways, of all his self portraits. He stares serenely but unsmiling off the page, his fringe flopping across his forehead. In his hand is an etching needle. I imagine he is daydreaming. Daydreaming about an empty road in Scotland, a dark mountain and buckets and buckets of rain.

Mathew Clayton