by Hannah Hamilton;

Gonna see the river man

Gonna tell him all I can

’bout the ban

On feeling free.

– Nick Drake, ‘River Man’

Rivers can be metaphors for many things. Metaphors for life, for its twists and turns, for the suredness of its path, for our uncertainty of what lies ahead. For times of peace in deep, calm waters, for times of struggle in the turbulence of the rapids, for times of submergence when hard bedrock yields to soft sand, creating hidden whirlpools and turnholes that threaten to suck us under their untroubled surface. Metaphors for the flow of time that’s constant in its pace but relative in our experience of it: going fast when we’re paddling frantic up stream, and slow, when we’re floating down, on our backs, gazing up at the clouds, letting the current do with us what it will. And metaphors for memories. That ethereal lifeblood that courses through our lives just like a river, connecting the babbling brook to the broad estuary, giving us a place, a direction, a stage, a reflection.

Rivers flow in all of us, and us in them, and in the sublimeness of their presence we find ours.

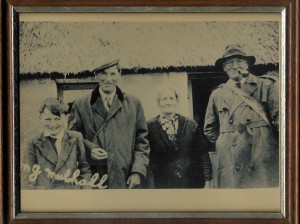

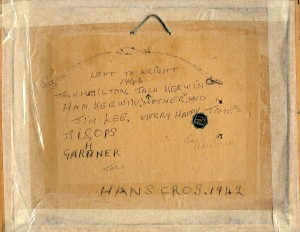

In his own way, my father taught me this. Not in words, they were not his strong point: as a peasant child in 1930s rural Ireland, he emerged illiterate and innumerate from two years of schooling, an experience that’s greatest impact was felt on the temples of his head, the lobes of his ears and the palms of his hands. He recalls being beaten by the teacher for ‘being thick’, so he wouldn’t go to school, and instead opted to be beaten at home by his father for truancy. School registers from the time record one of two excuses: ‘Wet day no clothes’ or, more frequently, ‘Gone fishing’.

What I learned from him came in more subtle ways than that of lecture, both in retrospect and in riddle, that required a certain amount of water to pass between the arches of my bridge to be understood. But now, I understand.

Because that scrawny malnourished child with no shoes and no electricity, that picked stones out of pratie (potato) fields for pennies and knew the fear of God like the back of his hand instilled in his child, a child of 1980s relative affluence with a full belly and nothing for wants, a sense of what it is to know oneself through nature, to find your place in this world, and in that place be free. His lesson was his life, and his classroom his river.

—

Aside from the mechanics of classic cars to which he devoted 40 years of his professional life, my father’s greatest passion was fishing, and I remember my first proper outing with him like it was yesterday.

I was five, and visiting my Granny Ireland for a fortnight on holiday – an annual pilgrimage to the paternal homestead. Holidays to me smelled like burning turf and tasted like red lemonade, Galtee cheese and soft whip 99 ice creams. My daddy was my hero. He was taking me fishing For The First Time and I knew it. Green wellies with frogs on the toes, dungarees and a lick of white blond hair, bounding eagerly over rickety fences and through meadows, leaping into mansize footprints in grass, desperate to share, to the banks of the chattering Nore.

I remember watching enrapt and bewildered at his rituals: threading the cast through the eyes of my little rod (black, with red threading and a cork handle) and knotting the end deftly around the eye of a huge (to me, at least) hook and moulding a blob of “Ssssh Hannah Don’t Tell Anyone” orange Playdough (salmon spawn, highly illegal, even in 1988) around its barbaric-looking barb. He sat me down on the bank at the top of the rapids and cast my hook under a large overhanging Sally tree and into a sandy hole he knew well. He handed me the rod, and rifled through the flaggers (long riverside grass) for a gabhlóg – a Y shaped stick – to act as my rod rest. He found one, dug its tail into the earth, rested the neck of my rod in the V and hunkered down to look me square in the eye.

“Now, Han, this Is Very Important. When the tip of the rod goes like this (cue his forearm in electric shock), you call me. Ok?”

“Ok.”

Thoroughly determined, I remember focussing on the top of the rod and willing it to move. I was sure it would if I just tried hard enough. And it did. Having made it no more than 30 yards upstream, he heard my urgent squealing: “Daddy! Daaaaaa-deeeeeee! The rod’s shakin’!”

He strode over in no great hurry, and I remember feeling frustrated that he wasn’t sprinting. “Are you sure? Maybe it’s just settling down in the current,” he offered, in his wisdom.

But no. Out from the water emerged a slippery, silver prize, more precious than gold, struggling to escape the confines of my net. He caught it in his big fist, stuck his fore and middle fingers down its neck, snapped its head back and in my triumphant hands he placed a half a pound of glory. I shone, nay, beamed with pride.

He took a clutch of grass, put it in our old battered fishing bag and gently lay the trout to rest on top, before casting out another blob of Playdough (this time with two little hands helping). Again, I sat and waited, and again – in a matter of minutes – the tip of my rod went into a violent spasm. Again came the squeals, the splash, the crack, the glow of father/daughter pride. Five times in total, if I must boast. Beheaded, gutted, floured, peppered, fried. That first time remains etched in my mind’s ore not just as the first time I went fishing, but also as the only time I was ever to catch more fish than my father. He only got three.

But he played a clever game, knowing that if there was any chance of me becoming a fisherwoman, I had to catch a fish on my first go. (Later, I found out, that that was the one and only time he had ever used salmon spawn – or trout’s heroin, as it can be known – to lure a fish, and that I was the intended prey.)

I have tried to repeat that first success many times, albeit with less advantageous bait. Pales of warm soapy water brought forth maggots from Granny’s back garden, though all I seemed to catch with them were hideous eels that squirmed and twitched, even after their heads had been chopped off. (My cormorant uncle always gave them a welcome reception, however.)

The family moved wholesale to Ireland when I was 11, taking over Granny Ireland’s house; two fences and one meadow away from the site of my debut, and opposite a small stretch of Noreside pasture known to us as the River Field. It consisted of 4.3 acres of un-tilled land that was liable to flood and half a kilometre of neglected, un-fished river that my father had dreamed of owning since his boyhood days, a slice of heaven that’s divinity was preserved in a stratum of memories. He and his seven brothers and sisters had played, caught dinner, shat and had their annual bath in that field, and Granny had washed the family’s clothes on its banks.

In 1996, he bought it from a local landlord, whose family he had known through four generations, and on whose farm he had toiled. It was the end field – the runt of their agrarian litter – but its acquisition was still a rarity. In Ireland, farmers don’t sell land. His cause was aided in part by changing attitudes of younger generations of landowners, but also by my father’s generosity in youth. He never forgot Old Mr Phelan when he’d caught a few trout.

Diggers respectfully tidied the bank, black sacks of household waste were wrenched bare-handed from the bed and 500 native trees were planted in a bid to restore something of the local wildlife’s natural habitat.

It was in this field that I learned to fly fish, under my father’s strict instruction. This, he informed me, with an elegant crack of his 12 foot split cane salmon rod, was an art form, and one to which all fishermen aspire. I was taught to tie flies in the dark. I learned to anticipate the rise and select the appropriate fly (sedges and green olives the favourites, black gnats after 10pm). I perfected my cast and put my own spin on the motion (born of necessity, I did not have my father’s biceps) that allowed me to present my fly to the fish with the finesse of a silver service waitress, anywhere at all on the river. He said that was the mark of a good fly fisher. I took his words seriously, and practiced casting onto a rise in a deep hole under a tree on the other bank with the wind against me till my hands filled up with welts.

Summer nights by the Nore. The swish of a cast. The cold rush of water around my legs (we never did care much for waders). Diamond stars in a pitch black sky. The splash of sprats jumping. The deep tantalising gulp of big trout rising. My rod. My daddy. And me.

—

In the years that followed, life by the river changed course and ran between us: him steadfast and oblivious on one bank, casting away merrily, building up a fishing school, manicuring his banks; and me, stubborn, proud and neglected, growing up The English Kid in the excruciating glare of the Irish catholic convent school system on the other. We diverged. I hung up my rod and moved to the city to pursue a treacherous but ultimately successful career as a rock and roll journalist, a passion of mine he cared not to comprehend, and I came to resent the waters he allowed to consume him deeper than his own blood.

When at 17 I got a commission (and, later, an internship), from the country’s biggest music magazine, it took him two years to remember the name of the title. When I moved back to the UK at 21 to join the rest of the sprats throwing themselves against music industry’s weir, he could never remember which city I lived in. When I tried to converse with him over the phone, he’d only ever offer the same specific phrases. I thought he wasn’t interested in me, and took his neglect deep into my heart.

But it wasn’t until he introduced my mother to me as my uncle that I realised that this cocoon he existed in was not by choice.

Three years ago, he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, and nine months ago was taken into full time care. For a man who has never tasted alcohol, who has never smoked a cigarette, who has never touched a narcotic, who has spent every single day of his life out doors, who until a year ago could do a chin up, flip his legs over his head and land on his feet, to be locked in an air conditioned ward on a cocktail of drugs is beyond hell on earth.

Our only consolation is that he doesn’t remember.

—

For my part, I went to India, re-discovered my heart and the importance of family, returning just as he was taken into care. I moved back to Ireland then and am still here, with my mother, doing what we can. Nature is slowly consuming The River Field, and the banks are growing over. Nevertheless, with youth and blind ambition on my side, it is my hope to re-open the Inchbeg Fly Fishing School – as it is known – next season, and to donate some of the proceeds to the Alzheimer’s Society.

—

The water has changed. My father has lost his river, and I now walk its banks alone, more than a little lost myself. But through my sorrow it gently reminds me, in the ripples and gurgles of that old familiar voice, that we each have our own course to run; that as tributaries dart from that same river seeking their own place amongst the earth, so must I. And there I find, safe in nature’s glistening example and comforted by my own precious memories, that I am not consumed in a whirlpool of grief. Through these waters, my father has bequeathed to me a metaphor for peace in troubled times. And in them, I too have found what it is to be free.

© Hannah Hamilton, 2008

Contact inchbegfishingschool@gmail.com