Jonathan Newdick on why the unadorned phraseology of Adrian Bell’s ‘Men and the Fields’ paints the most meaningful pictures. there is another reason, too, for the importance of this book to him . . .

Umbrageousness.

You find this impressive word a little over half way through Men and the Fields and it’s the first time that Adrian Bell uses a word that would be rare within the conversations of the farming people about whom he is writing in the late 1930s. Bell is mostly unimpressive and it is this aspect of his writing which makes him so readable, so enjoyable and (and this is not a contradiction) so impressive. As the best art historians can discuss a painting without having to resort to to the clichés of academia so Bell makes his own pictures with beautiful and endearing simplicity. His son Martin twice acknowledges this in his short foreword to the new edition of Men in the Fields ‘. . . [he wrote] a series of observations of country life.’ And ‘He painted with words.’

Perhaps this is why Adrian Bell appeals so much and so directly to me. As an artist, and primarily, one who draws, I like to make drawings not of things but about things. I like to tell part of a story and leave the viewers to take the narrative in directions and along paths which I may not have seen. Bell does this so well. Chapter ten begins with these words: ‘The way to the stackyard from the fields is harvest worn. Straws hang from the boughs of the elms . . .’ Although later in this paragraph he does describe in more detail the surroundings of this path (it might even be a road – but it’s a narrow one, no tarmac) it is those first two sentences that return me to that particular place that only I know and remember. We all remember it differently and it’s the phrase ‘harvest worn’ that does it. To achieve such unimpressive simplicity as this is a rare gift. It’s the same with drawing. Drawing, writing – they are both texts with no real intellectual differences although, of course, quite different from a practical perspective.

It is not just the sweet economy of Bell’s sentences which evokes such a sense of location, both geographical and historical. There is also the understated but implicit suggestion that the places about which he writes are important – so important as to be at the centre of the world. Today, when nowhere in England is remote, we frequently and inappropriately describe some village as being ‘miles from anywhere’. Bell refers to this strong sense of place only once, in chapter ten: ‘It was not then “miles from anywhere”: there was not that sense of the centre of things being elsewhere . . .’ Actually, he is here looking back to an indefinite time before he was writing but from today’s standpoint we can easily read that phrase as referring to his time.

Bell was not alone. These were the days when you could be a thinking, even philosophical, farm worker and not be that much out of the ordinary. T. Hennell, who was primarily a visual artist and who would later contribute to the government funded Recording Britain project, published his Change in the Farm in 1936. John Stewart Collis begins his The Worm Forgives the Plough with ‘It was April 16th, 1940’. There were others, yet Bell seems to have lasted longer than most. It wouldn’t happen now, or at least, the genre would be unrecognisably different. Today’s equivalent of Bell (he’s probably Polish and speaks little English) sits in his air-conditioned tractor cab listening to the beat of Metallica and he follows instructions from both mobile phone and sat-nav. He is unaware of and immune to those aspects of farming life that Hennell, Collis and, above all, Bell wrote about and made pictures of. He is immune to nature and nature is irrelevant to him. Bell, by contrast, was a part of nature, as much as the soil was, the earthworms within it and the elms above it. I remember my dad (himself a thinking farm worker) saying that he worked not on the land but with the land. That’s what is different now.

Yet Bell neither glamourises and nor does he romanticise. He was writing at a time of great uncertainty, both on the farm and in the wide world. The first edition of Men and the Fields was published in June 1939 and you didn’t have to be a clairvoyant to recognise trouble ahead. Change in the world and change on the farm. In chapter five he writes: ‘ . . . he remembered his father’s stackyard full of wheat, barley, oat stacks; acres of hops, and yards full of bullocks and pigs. To-day it was all grassland, and the men who used to work there . . . were all gone on to road-haulage and bus-driving.’

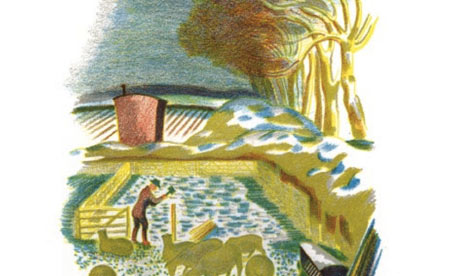

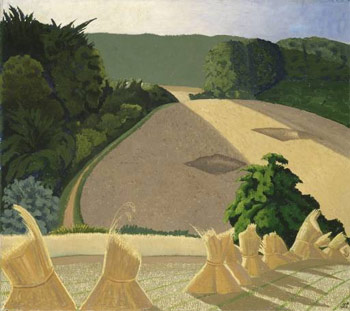

Not all. My father was one of these, though in a different part of the country. He joined the RAF where, fortunately, his eyesight was not fine enough to enable him to fly. Ground crew he was, and deep into the war, in September 1944 he went into a bookshop in Wells and bought a copy of Men and the Fields. Ten and sixpence. Drawings and lithographs by John Nash. First edition. But at that time the only edition and nothing really special. It’s special now. Special to me because he’s written his name and date on the front endpaper. Fountain pen and a fine italic hand that you wouldn’t associate with a farm worker. And special to anyone today who enjoys books because, regardless of its literary merits, it is a good book, a well made book. A book which sneaked into production just before English publishers were forced to adhere to the Book Production War Economy Standard.

B.T. Batsford (15 North Audley Street, W1) knew a thing or two about books and would also have known that the Bell/Nash collaboration was something unusual, something worth spending some money on. And they did. They had it printed at the Curwen Press, as good a printer as you’d come across in those days and they used a heavy cartridge paper which, even after seventy years has retained its creamy whiteness without becoming darker at the edges. The Baskerville type sits well on the page and the minimal decoration (just a thick and thin rule between the running heads and the text) is a neat typographic compliment to Bell’s own economy. Each of the six lithographs is printed on a smoother paper than the text pages and each is so skilfully tipped in that even now only one is beginning (but only beginning) to come adrift. These were the days, of course, when publishing houses were run by publishers who loved books. Today, admittedly with some exceptions, they are run by accountants who pander to the whims of banks whom no-one now trusts.

Little Toller Books, the publisher of the new edition of Bell’s book may be one of these exceptions, I don’t know, but certainly they have made a good attempt at a decent paperback. Of course it doesn’t have the dignified charm of the original and to reduce production costs the lithographs (printed, I assume, offset litho) are now grouped together in the centre of the book rather than being evenly distributed throughout the pages. This is a shame, and it’s a shame, too, that their colours have become rather brash and unsubtle and that the line drawings have lost so much detail. Typographically it reads well and while Monotype Sabon (thankfully used here with non-lining figures) is a fine typeface it was designed well after the time that Bell was writing and I would have preferred something more contemporary.

But these are the reactions from someone who not only has a history of book design but is also privileged to have an incomparable first edition Men and the Fields. Anyone without these would find the new edition both charming and at the same time could read it as an important literary and historical document. An opinion which Bell himself would never have acknowledged, I’m sure. The really important thing, however, and this goes beyond all pedantry, is that once again this text is widely available and that anyone who enjoys pictures made with words and whose dad didn’t leave them a copy of the first edition should go out and get one.

Jonathan Newdick is an artist and writer. To find out more about him and his work visit www.jonathannewdick.co.uk

Men and the Fields and other Little Toller titles can be bought from the CBTR shop.