Jude Rogers on ‘East of Eden’ by Taken by Trees. Out now on Rough Trade.

I first heard Victoria Bergsman’s voice – Swedish, strange, sleepy and sweet – on a soft, summer evening in 2004. I was new to music writing, and working at the Word Magazine as a tea-making, phone-answering, odd-jobbing Girl Friday. I was at the office late, on my own, sorting out piles of post, and a sleeve caught my eye by a band called the Concretes. It was white as a lily, but brightened up by a drawing of a cat in dark red. I slipped the CD into the tray of our dusty work hi-fi, turned up the volume, and fell peculiarly, quirkily, madly in love.

The Concretes’ first album, for many people, pivoted around the sun-dazzled sugar-rush of You Can’t Hurry Love, a song with a title and sound that tilted its indiepop beret towards the 1960s. Not me. I clung to the stranger, folkier moments of the record, and the spirit of melancholy that drove them. I loved Chico, full of glockenspiel notes falling like glassy tears, in which Bergsman told me about the friend she would cling to “when I’m out, when I’m out, when I’m out in love”. I also loved her sulks around the sad carousel swing of Warm Night, and the shy album opener, Say Something New, which introduced us to a singer mourning “all the things I had mind for you and me”.

In the world of The Concretes, things started to change. The band’s second album, In Colour, was pristine and polished, and had less vocals by Bergsman, and more by icy blonde Lisa Melberg. My tenderness for them started to fade as their sound got brighter. And when Bergsman left The Concretes in 2006, the same year that her vocals on Peter, Björn and John’s Young Folks took her into the mainstream, the band lost their relevance for me completely. Bergsman’s lovely, offkey voice was their soft, beating heart, and her odd, folkish qualities heated their blood.

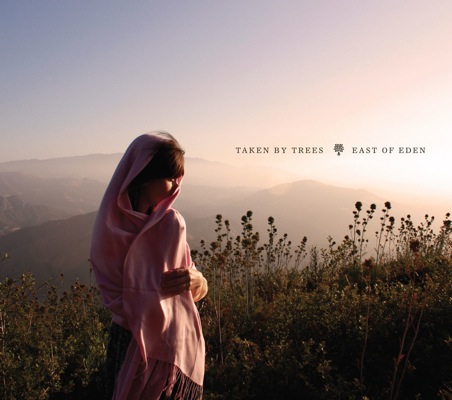

Since she has been recording as Taken By Trees, Bergsman has let her individuality blossom. 2007’s Open Field was a beautiful debut: simple, stripped bare, her voice breathing gently over guitars, sparse percussion, and piano patterns. This year’s East of Eden, however, is something entirely different. It was made not in the icily glamorous hub of Scandinavia, but in Pakistan, and inspired by Bergsman’s love of qawwali – a form of Sufi devotional music made popular by late Punjabi singer Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. Intended to take the singer and listener into a trance that bring them closer to God, it is also usually made and recorded by Muslim men – and not white-skinned, doe-eyed girls from Northern Europe.

On paper, the worlds of this Swedish former indiepop singer, and the strict religious people with whom she played on this record, could not be further apart. But on record, somewhat mysteriously, it clicks. There is something about Bergsman’s peculiar voice that works in this setting, it being shaky but strong, romantic but serious. You can hear echoes of its tender, higher register in Musharaf Ali’s high, woody flutes and Muhammad Aslam’s violins, and ghosts of its low, bassy aches in the scampering percussion – sometimes in Sain Muhammad Ali’s tumba, a long thin instrument which plays different pitches, and Ranja Sain’s dholak, a tuneless hand-drum.

In terms of her lyrics, Bergsman is in familiar territory, singing words both wide-eyed and slightly woebegone. When she sings, on the wryly titled Greyest Love Of All, “when you’re alone, and you long for friends/And then you’re with friends, you want to be with yourself”, these words somehow don’t sound like the protests of a fusspot. They come across like lovely, child-like meditations. Elsewhere, loss hangs much more heavily. In Watch The Waves, we hear her sigh, “I didn’t know how much I loved you, until the day you went to sleep”, while on opening track To Lose Someone, just like an echo of what happened The Concretes’ debut album, a sad story unfurls. A girl loses her love in a crowd in an unfamiliar town, he turns up in the river, and there is the sense that fate might have dealt this narrator an unlucky hand. “I wish I could’ve told you that no one can take your place”, Bergsman sings, the atmosphere shimmering with shyness and disorientation.

But there are broader issues to consider on this record. Many critics and fans have questioned Bergsman’s use of Middle Eastern sounds and influences and called her methods exploitative, especially at a time when world music – as it is still unhelpfully labelled – is proving a rich resource for indie artists. Take Vampire Weekend’s dizzy afropop, Friendly Fires’ skittering samba, and The Acorn’s South American rhythms as three examples of bands who have dipped into other musical cultures. But Bergsman, to her credit, has gone a step further than them. She has made an effort to immerse herself in the country that her influences come from, and used local musicians to develop her songs. Hearing the results of her field recordings and collaborations on this record, she is also making interesting links between the folk music she knows, and the folk music she wants us to hear. For that alone, we should applaud her.

But it is certainly strange that her most persuasive connection between the West and the East comes on her cover of Animal Collective’s My Girls. Made with the assistance of Noah Lennox, aka Panda Bear, Bergsman has changed it into a tribute to the people she loves back home, called it My Boys, and filled it with harmoniums, vocals of her new friends, and stark, steely strings. It creates its own heady world, and it rustles with emotions, taking me back to that office desk in 2004 when Bergsman’s strange, subtle voice first spoke to me directly. As she sings, I feel my “solid soul and the blood I bleed” too, and remind myself why Bergsman’s talent is ours to be loved.

‘A Rainbow in Flight’ by Jude Rogers, can be found in our book, ‘Caught by the River – A Collection of Words on Water’