by Neil Sentance.

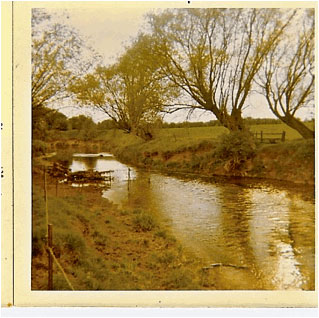

My grandparents and great-grandparents farmed near the banks of the River Witham on the Lincolnshire-Nottinghamshire border from the 1920s. In the 1970s, I spent so much of my summer holidays rambling over that farm, and in particular to the ford at the riverfield. The village, once a Great North Road staging post, was by now bypassed and unheeded on a low rise above the dual carriageway. In its upper reaches the Witham is the archetypal turbid and sluggish Midland river. A meandering backwater, it’s bottomed with dark clammy mud, the colour of the old clay pipes often turned up by ploughs hereabouts. At the Fallow Lane ford though, the water is faster-flowing. In summers then, the banks were edged with linen-white sweet briar and dog roses, clumps of alders offering branches for the blue spark of kingfishers. Sparrowhawks weaved through the hawthorn. The long grasses were lathered with cuckoo spit.

At the ford, alterations had been made some time after the war. A paint-peeled wooden footbridge (descendant of a packhorse bridge?) had been replaced with a paint-peeled iron and concrete one and a weir had been built immediately upriver. A depth gauge stood midstream, battered by stones hurled by us kids in long contests on the bridge. In those days before the curse of ubiquitous 4x4s, only farm vehicles would cross the ford with alacrity, unless at midsummer when the water levels were lowest. Grandad would truculently dredge some chancers out every year. But one summer holiday trip on the way to Skegness we picked up the grandparents in Dad’s 1964 Vauxhall Victor Estate and, weighed down with heavy leather suitcases, our car barely made the crossing, the exhaust pipe catching on a riffle, before a heavy foot on the accelerator span us to the other side. That maggoty old baker’s van had had a forlorn history but it’s the car of childhood I remember, the Ford-Traverser.

The ford was the village boundary and the frontier of our summer holidays. Beyond was the gravelly shore and the parishes of Westborough, of narrow lanes and Roman ghosts, and Long Bennington by the roaring A1 to Newark and the North, terra incognita to eight-year-olds. But not to cousin Noel. Noel was several years older, tall, good-looking, cool but not standoffish. He’d roam over to Dry Doddington and Claypole, the bigger villages downriver, on his Raleigh racer to meet the girls he’d laughed with on the double-decker school bus during term time. His jeans made a characteristic swish, the flares whipping the air when he walked. I tried so often to emulate that sound in threadbare hand-me-down cords but never captured it. He was also a skilled practitioner of the art of playing dead. Tickling, pummelling, shouting down his lugholes, nothing could budge him, until suddenly he’d rise up like a kraken and chase us youngsters across the field, bellowing like a bee-stung bull. One time we had played farm cricket in the old dairy and a smashed top-edge had punched a hole in the asbestos roof. We ran off to the river and hid for the day down at the ford where Noel took us to watch rainbow trout leaping up the weir. He’d be chucking off his trainers and socks, rolling up trouser-ends and wading out and up the concrete face, smiling as he tried to catch fish with bare hands. Those iridescent-bellied and spot-finned fish always just eluded him, curvetting away like the dolphins found on Roman brooches in the fields nearby. Those river days shine now, me and my mates stepping out to tiny tapering islands in the stream or lying in the grass watching the rippling waters, wreck-strewn with the sticks and stones we’d cast into them. With Noel around, all was right with the world. Much later, he left the village, worked in the TV industry, came back long enough for a last falling out with the folks, and then he was gone and never seen again.

By then the ford was long a nexus in our family history, differently coloured for all of us. Dad would take long walks down there from the farmhouse on Sundays with his brothers-in-law, escaping the post-prandial family clamour, and especially, Grandad, their father-in-law. Mum would walk down to the ford too, other times, with me as a little lad and with Granny, walking the terrier Peg (bought from gypsies as a ratter, hence the inevitable name) or Floss, the redundant collie. At some distance behind too would be the cat, following us unbidden for the stroll, and keeping out of dog-range. Mum would talk about her child days at the ford, summer holidays of cow ‘tenting’ (tending). She would take the cows down Long Lane to the ford, leaving her sister stationed at the farm end, and the cows would chomp the grasses of the wide roadside verges. Once the cattle had reached the ford, Mum would lead them across to the other verge and send them back on their way to the stackyard. This would take all day and happened regularly through the summer months – for Mum this wayside transhumance mostly entailed sitting curled up in the long grass reading Enid Blyton or Louisa May Alcott, only needing to stir to shunt the beasts round again.

Mum could also remember her own grandmother, the redoubtable Granny P, set to hard work in the meadows where the Foston Beck (we are in Viking country) meets the Witham, willows stooping over the river edges, the fields filled with cowslips. They would choose a plot and pick all the flower heads until withy baskets were full, or until the Westborough church bells tolled, the only call for time, a worldly angelus. The flowers were stewed in vats with brewers yeast, left for the spring to ferment, and tubs of cowslip wine filled the pantry shelves through to the autumn. A few years on, 10-year-old Mum would be sent back down to these fields, along the Green Lane, for hay turning and baling in an old gunmetal grey Ferguson tractor, and then back across an ancient ridge-and-furrow landscape, for centuries unaltered, and past the dark hulking superstructure of a vast wooden barn called the Deauvilles, standing like a vision of a black-masted ship, a rat-ridden East Indiaman perhaps, anchored over swells of wheat and barley.

Mum was only a few months old during the Hardyesque tale of Great-Grandad and the bull. Great-Grandad P was a yeoman butcher who rarely went down to the riverfield other than to drown kittens in sacks. One day in summer a few years after the war he left the slaughter room in a rage about the riverfield gate being left unmended, his smock still streaked with blood. The prize bull’s horns gored the butcher, and he died by the ford, his hands lying by his side cold and white like knapped flint. His son, my Grandad, didn’t want the bull to be destroyed, but this time yielded to others’ opinions. He kept the bull’s nose ring though, hanging it from a nail in his workshop for decades after.

I went back to the village recently. Grandad is now dead, the farm sold, the stackyard an executive housing estate, 4x4s in garages made from eighteenth-century bricks reclaimed from the torn-down dovecote. The ridge-and-furrow field has long since been obliterated by agri-farming, and the Deauvilles demolished and replaced with a colossal corrugated potato store. Mum and I and my wife traipsed down to the ford. The footbridge is still there but the fish had the further obstacle of a burnt out car, joy-ridden up the weir and abandoned. Mantles of keck (cow parsley) and ragwort smothered the banks, but the fishing was strong, although it turns out those rainbow trout of the 70s may have really been highly coloured brown trout and not American interlopers after all.

As Roger Deakin says, rivers are numinous, magical places suffused with memories of childhood. Sue Clifford says they ‘etch time into place’, watery worlds, full of play pools and testing grounds, on the borders of our childhood lives. Maybe a river runs through all the pictures of our growing up, the youthful rapids to the old-age estuaries. I live in West Dorset now and the rivers of my own children’s play and dreams are chalk streams and winterbournes, swathing through to the fossil coast, then spreading in mini-deltas, like the Wynreford creek that snakes out through the shingle at Seatown where the summer kids make dams, and dig trenches, and form culverts and tickle fish, and make their own memories.