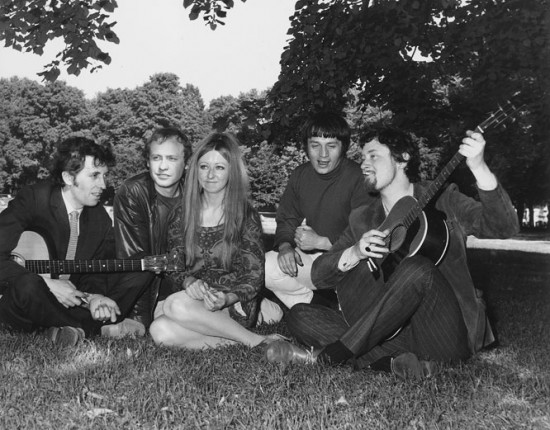

Pentangle in a London park, June 1968. Left to right: Bert Jansch, Danny Thompson, Jacqui McShee, Terry Cox, John Renbourn. Credit: Topix

Pentangle in a London park, June 1968. Left to right: Bert Jansch, Danny Thompson, Jacqui McShee, Terry Cox, John Renbourn. Credit: Topix

by Rob Young. From his book Electric Eden (Faber & Faber paperback).

The swimmer arches her back, bobbing between dreaming and waking, just as her face rises and sinks at the liquid threshold of air and water. Sunbeams dazzle the surface, dilating into the sleeper’s vision as if through a fisheye lens. Up on the riverbanks, on each side, she is lazily aware of ‘Moonflowers bright with people walking/Drinking wine and eating fruit and laughing . . . Death alone walks with no one to converse with.’

The gracious paradise evoked in Pentangle’s song ‘Pentangling’ might be a vignette from the Thameside of William Morris’s News from Nowhere. The sunlit hippy dawn meets Morris’s bucolic medieval Arcadia. The weather is perpetually hot, the sky clear, ownership is banished, and a carefree, effortless existence is nourished with an abundance of good things to eat and drink. It is, in Donovan’s words, a ‘land of doesn’t have to be’ – a flower child’s utopia where the only thing missing is a big rock candy mountain. ‘You know I fished just a little to ease my body and soul/ Just sit and dream on the riverbank/ Let my mind relax and let my consciousness be easy and free.’

Pentangle’s theme song first appeared on their debut album, The Pentangle, released in May 1968 and recorded during the previous month and a half. The arrangement fits the soft-focus vapour of the lyric: Jacqui McShee’s spritely trill blurs and elides certain words, making ‘swimmer’ sound almost like ‘summer’. The song’s evolution over the ensuing half-decade provides an index of the freedoms opened up by this mercurial unit. The seven-minute version on The Pentangle includes a short instrumental break, but by 1970 ‘Pentangling’ was being routinely protracted to twenty minutes or more, with a lengthy acoustic-bass solo by Danny Thompson at its core, bowing, sawing and plucking in a manner that recalled Jimmy Garrison’s deep lacunae in John Coltrane masterworks such as A Love Supreme. Propelled on Terry Cox’s airpockets of brushed drums, the twin guitars of Bert Jansch and John Renbourn fill out the rest of the tableau, pruning back to reveal Renbourn’s long, probing lines of enquiry into the tune before an invisible collective nod heralds a synchronised dive back into the main theme.

The group grew organically out of the mulch of acquaintances, collaborations, workaholic Tin Pan Alley sessioneers and friendships that fertilised the London folk/blues/jazz milieu of the mid-1960s. As mentioned in the previous chapter, for a year from around the spring of 1965 Jansch and Renbourn both lived at 30 Somali Road in west London’s Cricklewood district. The large, rented, semidetached house was also occupied by the three members of The Young Tradition, and quickly became a kind of unofficial folknik drop-in centre, both for London musicians or wandering minstrels rolling through town. Anne Briggs frequently crashed there on her trips away from Ireland, where in 1966 she was living with her lover Johnny Moynihan, the bouzouki-strumming singer of Sweeney’s Men. Renbourn was in a duo with Californian singer Dorris Henderson, holding down a regular slot on the TV show Gadzooks! It’s All Happening, a topical, gossipy, pop shop window presented by Alan David and Christine Holmes. Portraying itself as a programme with its finger on the swingin’ pulse, the first series featured guests such as Lulu, Marianne Faithfull, Peter Cook, Tom Jones, Sandie Shaw and Davy Jones and the Manish Boys – the firstever television appearance by the man later known as David Bowie (promptly banned for wearing his hair too long). Alexis Korner led the house band, convening the future rhythm section of The Pentangle, bassist Danny Thompson and drummer Terry Cox.

Over the sweltering, dusty summer of 1966, as England basked in the glorious aftermath of its World Cup win, Jansch and Renbourn’s parallel careers made a decisive gear shift. Renbourn recorded his great second LP Another Monday in the makeshift studio at Bill Leader’s Camden flat. Four songs featured the voice of Jacqui McShee, a regular folk singer since 1960 who by the middle of the decade was running her own folk club in Sutton, near Kingston-on-Thames. She booked the Jansch/Renbourn duo for a gig, an engagement that led to her working the folk clubs in partnership with Renbourn in the latter half of the year. The two guitarists relocated to a new flat in St Edmund’s Terrace, on the edge of Primrose Hill, and there recorded two watershed albums that took the decisive step towards the loosening up of the conventions of folk-music presentation. Bert and John was taped in the living room of their new flat, and presumably stands as an accurate record of the casual, freewheeling ambience of their shared lives at the time. It’s the apogee of the breed of eclectic, pan-cultural guitar collections proposed by Davy Graham, but even as Graham spent the rest of the 1960s diluting his repertoire for his albums in a misguided bid for popular acceptance (his singing never up to the standards required to handle Lennon–McCartney tunes and jazz standards already owned by the great entertainers), Bert and John sounded lean and hungry, the tracks’ elaborate narrative tapestries stitched fluently and, occasionally, with a note of urgency. After the rollick of Charles Mingus’s ‘Goodbye Pork Pie Hat’ and the complex twelve-bar ‘Tic-Tocative’, Jansch and Renbourn’s compositions become concentrated to a degree that we might define as a more British register – less concerned with a sense of widescreen expansiveness, more of a close huddle, a smallness and focus on detail and rhythmic attack. To those qualities ‘Stepping Stones’ adds a frisson of melancholy. And in their dignified rendering of Anne Briggs’s leave-taking song ‘The Time Has Come’ – its first recorded appearance – was the intimation that fresh pastures beckoned.

Jansch’s Jack Orion – recorded at almost the same time as Bert and John – consolidated the approach he had nurtured informally in tandem with Anne Briggs: eight songs cast in a setting that was pure Albion. With the dying banjo strains of the opening Appalachiantinged ‘Waggoner’s Song’, all echoes of an Americanised hobo music faded away altogether. Using the Davy Graham DADGAD tuning to sustain a driving, minor-key Celtic drone feel throughout, Jansch remorselessly broke down tunes like ‘Henry Martin’, the hardy perennial ‘Nottamun Town’, the Briggs discovery ‘Black Water Side’ and ‘Jack Orion’ itself, in a version which was effectively custom-built for him with the aid of Bert Lloyd, who adapted it from ‘Glasgerion’, one of the Child ballads of genuinely medieval Scottish origin. The erotically deceived harper of the earlier lyric becomes a fiddler who instigates a bloodbath that endsin the slaying of his servant boy, a princess and himself. The tune became a signature for Jansch, Pentangle and beyond: in 1970 the folk-rock group Trees turned ‘Glasgerion’ into a romping Grateful Dead-style freakout. But in the incredible string tangle of the 1966 take Renbourn’s interjections on second guitar careen off Jansch’s circular picking, like a roulette ball bombing off the sides of the wheel. He even has a crack at Ewan MacColl’s ‘The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face’, sieving its uncharacteristically glutinous sentiment through the retuned guitar strings and reconstituting it as an under-two-minute sigh of downcast yearning. Jack Orion staked out the cardinal points of the Pentangle sound.

Immediately south of St Edmund’s Terrace, where this music was clawed into shape, the paths criss-crossing the western half of Regent’s Park form the shape of a rough but unmistakable pentagon, whose sides are extended to form five star-points. The pentangle has ancient origins, traceable back to Babylonian sorcery and Greek hermetic philosophy. Linked to the motions of the planet Venus, it has been adopted as a magical symbol by pagans, Christians, Satanists and even Freemasons. In 1967 its universality across denominations and continents chimed with the inclusive spirit of the age. Renbourn complemented his own fascination for medieval and Renaissance pavanes and galliards by reading Arthurian literature, and chose the name Pentangle ‘To protect us from the evils of the music business,’ he jokes. ‘I don’t think we spent an awful lot of time thinking about names, but that one seemed about right. And when we visited America, the lighter side of the occult was being revived by the hippies, and the pentangle was the sign on the Tarot cards, and it all seemed to link up nicely.’

A second extract will follow tomorrow.

Electric Eden is on sale in the Caught By The River shop, priced £14.00

Read the review by Andrew Male.