Four Hedges: A Gardener’s Chronicle. Written and engraved by Clare Leighton Little Toller Books, Stanbridge, Wimborne Minster, 2010. Introduced by Carol Klein

Review by Martin Davies.

Surrounded by the clamour of iPod and Kindle, it is good to come across a book that quietly lets us know that the printed page is still doing perfectly well – thank you. Such is the case with Four Hedges, the latest offering from Little Toller Books of Dorset, an outfit committed to reissuing classics of nature writing from the British Isles. This much-lauded ‘chronicle’ first came off the presses of Victor Gollancz in 1935 when its author-illustrator, Clare Leighton, was at the height of her artistic powers. Two years previously her The Farmer’s Year: A Calendar of English Husbandry had produced quite a stir, with twelve plates measuring a staggering eleven by eight inches. The giant tome also represented a radical departure for its creator, known up until then as an illustrator of other people’s books. Leighton’s parents were both writers, and her partner, Noel Brailsford, was one of the leading contributors to the Manchester Guardian. Scribbling clearly came as second nature. The Farmer’s Year saw three impressions in as many months plus an American edition that gave its fledgling author the confidence to embark on a longer sequel reflecting her passion for the miniature worlds of flora and fauna she’d been exploring since childhood.

Four Hedges is divided into twelve months like its large-format predecessor, and has an opening sentence that embodies the author’s beguiling modesty and simplicity: “Ours is an ordinary garden. It is perched on a slope of the Chiltern Hills, exposed to every wind that blows. Dig into it just one spit, and you reach, as it were, a solid cement foundation. One might be hacking at the white cliffs of Dover.” Wordsmith as well as artist, Leighton transports her reader in an instant, be they fumbling pot-planter or experienced professional, to that barren patch of chalk – microcosm, laboratory and theatre all in one. (A stone’s throw as well from a much grander residence: Chequers).

That Four Hedges eclipsed Leighton’s previous achievement can be attributed to its rare combination of delicate wit, practical advice, original observation and generous illustration. There is something to savour on every page, while random browsing soon yields a handful of pithy truths: “A really good man should want to tend a garden, even if it is not his own; this is the decisive test” (p. 43); “It is the swelling of next year’s bud that pushes off the old leaf.” (p. 111). After destroying with boiling water a dozen (seed-eating) ant heaps, Leighton suffered nightmares which helped extend her liberal convictions to the humblest of the animal kingdom’s denizens:

How was I to know that in the scheme of things I was more important than they were? How, in fact, was I so certain that I was a more highly developed creature than the ant? They ate green flies off the fruit trees; what did I do of equal value? They kept the earth friable; what did I do comparable? Their ordered society seemed superior to our own; from what they could see, we were astonishingly indolent.” (pp. 71-2)

The circumstances which underlie this masterpiece of the genre are barely alluded to in the text, but are certainly worth mentioning here. Estranged from his wife for many years, Brailsford was twenty-five years Leighton’s senior and bought the plot in 1929 as a present for her. Although the couple never married, they designed their country retreat together from the ground up, and worked its soil with a rare dedication, transforming untamed heath into one of the most famous gardens in print. Immediately before starting the book they’d spent two months in Tyrol and Corsica, dispatched by Brailsford’s doctor in the belief that his important client needed complete rest. The trip was one of many Clare made throughout her life, and she brings the sharpness of a travel writer to every tiny (earth-shattering) discovery in her back yard:

It is the beauty of seed pods that strikes me just now [August]. The rushed blooming of flowers is over, and colour of flower has given way to form of seed pod. It is so wrong to think of the beauty of flowers only when they are at their height of blooming; bud and half developed flower, fading blossom and seed pod are as lovely, and often more interesting” (p. 76).

The description of the seed pod that follows is a model of lucidity, matching the engraving (carnation poppy) at its side. It would be hard to disagree with her holistic thesis as well, eloquently supported in recent decades by otherworldly images of pollens and seeds made with electron microscopes. Another example of Leighton’s roving intelligence is her take on sensory input:

The sensation of touch seems to be fading, and lazily we look at things with our eyes, and smell the more pronounced scents around us, ignoring the vast range of emotion that is within the scope of hand or foot. Few think of caressing a flower and enjoying the feel of its form and texture, the tightness of its bud, the hardness of its seed pod, or know the pleasure the hand can get from the surface of a tree trunk or a vegetable marrow. The peasant in the field will see a small bird afar off, or smell the change in the weather, or get happiness from the feel of his soil. We are poor creatures that we should call ourselves civilised, we who have only these blunted powers.” (p. 93).

Only an extraordinary and original mind could have angled a gardening book quite like this.

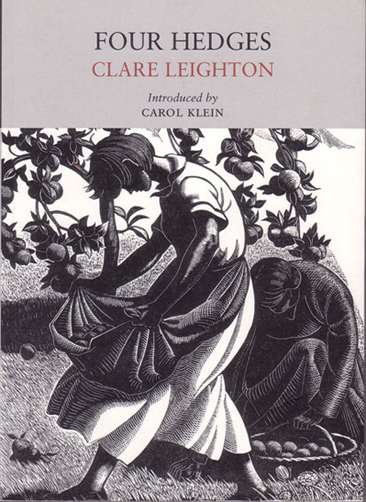

Many will buy Four Hedges for its engravings (the visual default) and they will not be disappointed. Leighton was a consummate craftsperson, champion of the natural and direct ‘white line’ then in vogue, as opposed to the Victorian-Edwardian ‘black line’ in which the design is created from the wood that remains after the rest has been cut away (exemplified by Eric Gill). One result of white line is that human and botanical subjects can sometimes appear a little dark, sharply silhouetted against the ivory whiteness of page and sky. The tonality matches the sombreness of north-facing slopes in an English autumn or winter, bringing out the ruggedness of those Hardyesque toilers. The cover features one of Leighton’s most successful scenes, ‘A Lapful of Windfalls’, in which two women are seen gathering apples in an orchard. Their ‘bronzed’ limbs are evidently sturdy enough to lug the plentiful harvest home and transform it into a series of magnificent pies. This was the last generation which worked the English landscape (and kitchen) with bare hands, and there is an elegiac aura to much of Leighton’s vignettes, celebrating a lifestyle on the brink of permanent transformation, not to say eradication. It was brought home in the following book, Country Matters (1937), which added a nostalgia – and even coyness – to disappearing traditions.

The prose of Four Hedges, by contrast, is unsentimental from beginning to end. It is a meditation for the mind, a delight to the eye, and a book which will make you murmur again and again, ‘How true!’ For the engravings alone it is worth the cover price, but when the poetry and nature insights are included – well, an absolute bargain. The publisher has done full justice to the delicate exchange between engraved image and printed word: the cover itself would have been fondled with delight by the author herself, while the design is faultless – paper, fonts, weighting, spaces. The finest ‘white lines’ in the superb botanical images, which might easily have been compromised, are all present and correct.

A final word about the title. Few cinema buffs have heard of an obscure Joan Crawford drama called Four Walls, released the August before Brailsford bought his plot of Chiltern soil. The film was a complete flop, and there is nothing to say that these bookish gardeners drew inspiration from it in naming their enclosed piece of paradise. But the coincidence is striking. The film also brings to mind Leighton’s lengthy residence in the United States from the late 1930s until her death in Connecticut in 1989. Her relationship with Brailsford came to an end in December 1938 as he immersed himself in Spanish socialism and she decided to move to America, where she already enjoyed a considerable following. There she wrote and illustrated two works on rural/maritime subjects, Southern Harvest (1942) and Where Land Meets Sea (1954), closely mirroring her earlier achievements on British soil. Leighton is really one of the few English artists to have made a major contribution in the field of Americana. Her entire life was full of admirable goals accomplished with style, and she deserves to be far better known. Perhaps like Dora Carrington – another underrated artist inspired and encouraged by a much older man – she might one day be portrayed by an actress who can do justice to her extraordinary combination of talents.

Martin Davies is founder-director of Barbary Press, whose Birds of Ibiza was recently reviewed on this website. Other titles include Leif Borthen’s The Road to San Vicente and Alexis Brown’s A Valley Wide, both richly illustrated with wood engravings. Davies is author/editor of two popular photo anthologies Eivissa-Ibiza: A Hundred Years of Light and Shade and Eivissa-Ibiza: Island Out of Time, and also edited Paul Davis’s Ibiza and Formentera’s Heritage: A Non-Clubber’s Guide, an illustrated companion to the architecture and archaeology of this underrated archipelago. Most of these (in various language editions) can be ordered directly from martind@telefonica.net and also from www.liveibiza.com and Amazon.

Four Hedges is on sale in the Caught By The River shop, priced £10.00