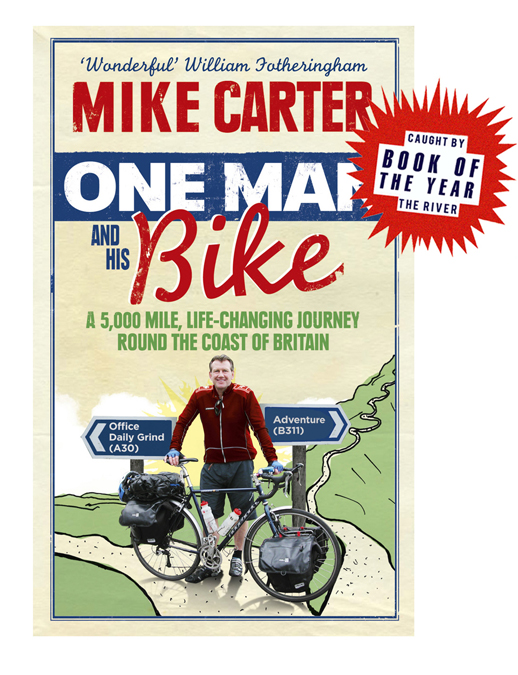

An extract from – One Man and His Bike. by Mike Carter (Ebury Press 2011)

If the small ferry crossings seemed to mark small endings and beginnings, new paragraphs if you like, I always felt when I left London that the county borders and the big bridges would feel like significant milestones on the journey, the ending and beginning of chapters. And so it felt that day, three weeks after leaving London, high above the Humber.

I was cycling next to the railings on the shared pedestrian/bike walkway. From the saddle, my head several feet above the railings, it felt like I was flying through space, the mudflats of the Humber far, far below, ships ghosting along underneath me, Immingham in the distance wearing its nicotine-stained bonnet. As I wobbled along, the thought occurred that if my bars clipped the railings, just inches to my right, I could easily be pitchpoled straight over the bars and out into space. But far from making me afraid, this just made me laugh out loud.

Halfway across, I stopped to take a picture of the view. On the railing was a plate carrying the phone number of the Samaritans. Next to it, tied to the railings with string, was a dried and shrivelled bunch of long-dead flowers, the heads hanging limply over cellophane now dirty from the fumes.

Stopping at a traffic light in Hull, I saw one of the city’s famous cream telephone boxes. Kingston-upon-Hull had been the only area of the UK not under the Post Office monopoly, with telephones being under the control of the council. So, in the name of civic identity, the phone boxes were painted cream and the crown omitted.

This made me think about the role a town’s ‘colours’ play in identity. When I was a kid, whenever we drove down from Birmingham to London to see relatives, the game we played was always the first person to spot a red bus. I can still remember how exciting that was. Ditto the deep-green buses of Liverpool, the maroon of Glasgow or the orange of Manchester. There was always a frenzy to see a Brummie blue-and-cream bus on our return home. The sighting of one always made me feel as if I were home proper, as reassuring after an adventure into a land marked ‘here be monsters’ as a comfort blanket.

Since buses were deregulated in the mid-1980s, colours change when franchise holders do, or when a marketing department’s got the fidgets. I know I’m a reactionary old fart now, but this makes me more than a little glum. I’d recently been back to Brum and seen that most of the buses were now painted in the red, purple and white of National Express. A little bit of me seemed to die, another connection with my childhood severed.

But are these things important in the grand scheme of things? I’d say that they are. Because where does it end? The colours of your football club’s shirts changing on the whim of a new owner, in the same way that the stadiums are now renamed after the sponsors? Whole towns renamed after corporations? We’re already seeing schools go down that road. In a world where everything can change overnight at the whim of a boardroom, I’d argue that it’s things like football stadiums and bus colours that can give us an implicit stability when everything else is mutable, liable to change or disappear overnight. But such is the modern world. It doesn’t mean that I can’t feel sad about it, though.

For the record, in Hull, many of the buses were painted in Stagecoach’s corporate colours of blue, white, orange and red. Preprivatisation, I believe Hull was a royal blue and white kinda place. After negotiating Hull’s Byzantine one-way system, I was finally out the other side, into the immutable open countryside and the arrow-straight lonely lanes through Stone Creek and Sunk Island. A handwritten sign on a post by a farm said ‘camping’, and I was directed by the farmer to a little field at the back of his house, with a basic shower room converted from an old breeze-block shed with a heavy steel door that banged in the wind. There were no signs up anywhere, though, so it felt just dandy.

In the rapidly fading light and still pouring rain, I pitched the tent, shoved my panniers into the porch and was just about to follow them in when I saw that the occupant of the only other tent on the site was heading across the field my way. ‘How do,’ he called, when about 20 yards away. ‘Saw you arrive on the bike. Come far?’

I told him what I was up to. I kept it brief, trying to talk in a manner that I hoped suggested I was not being rude, just not in the market for a long and meaningful. I eyed my panniers, now snuggled up under canvas. I also knew that somewhere in those bags were a couple of baguettes, some honey-roast ham and a slab of Boursin.

‘How marvellous,’ he said. ‘What a great adventure you’re on.’ The rain was sheeting down now and it was almost dark. ‘And you?’ I asked. I looked over at his tent. There was no sign of a car. ‘How are you travelling?’ He pointed down at his feet and shuffled them backwards and forwards. ‘On those. Walking round the coast of Britain. Not all in one go. Doing the leg from Berwick to King’s Lynn this time.’ ‘David,’ he said, and held out his hand. He wore little clear plastic spectacles. Beyond them were deep blue eyes that sparkled like sapphires.

He was 62 and lived in Bury St Edmunds. When on his walks he got up at 6 a.m. every day and hit the road, never knowing where he would end up that evening. Sometimes he would find a campsite, sometimes he would just rough it in a field. ‘I just love walking,’ he said. ‘Being in nature. It makes me happy. Done five thousand miles in the last five years, with only one blister in that time. Land’s End to John O’Groats, most of the major British trails. ‘These,’ he continued, pointing to his well-worn boots, ‘have cost me about 10p a mile.’

He said something about a wife that suggested to me that she was dead, but no, she was alive. ‘She doesn’t like camping. Lets me get on with it. We’ve been married thirty-eight years. I call her once a week just to let her know I’m alive. I picked a good ’un.’

David’s enthusiasm for the nomadic life oozed out of him; he seemed so alive and engaged with the world around him. But didn’t he ever get lonely? ‘Lonely? Good God, no,’ he said. ‘Haven’t got the time to be lonely. There’s so much to see, so many birds and animals and amazing views. I meet dog-walkers along the beaches, and there are always very interesting people to meet if you’re prepared to introduce yourself. I think the important thing is that I quite like my own company, am happy to be on my own, chattering away to myself. People must sometimes think I’m a right nutter.’

A young hare hopped up to us, as calm as you like, and just sat there by our feet for a few seconds. ‘That’s funny,’ said David. ‘Hares are usually such skittish animals.’ As if the hare suddenly realised what it was, it bolted at full tilt away from us, flying across the grass and then into the green wheat a couple of hundred yards away.

‘I used to cycle a fair bit too,’ David continued. ‘Took part in marathon club rides. Did 246 miles in twelve hours once.’ Nothing he said sounded boastful in the slightest. We’d been talking for about half an hour. I’d completely forgotten about the food awaiting me just inches away. I thought of the people I knew in London in their thirties and

forties who say how much they detest their jobs and are bored, who self-medicate with booze and drugs and seek their thrills on mini-breaks at five-star hotels in obscure European cities, eating expensively. There never seemed to be any real passion in their voices when recounting their adventures. And here was David, in his sixties, wandering alone, sleeping in a one-man tent in fields, eyes on fire with it all as if he’d just acquired the power of sight.

I wondered what this meant for my generation, many of whom seemed to have lost their appetite for simple pleasures; living in a world full of choice that has brought not happiness but a bitterness for the things they don’t have. ‘Good to meet you,’ he said. ‘I’m off to bed. Up at dawn. Going to try and get over the bridge by tomorrow night.’ He took out a piece of paper, scribbled a number on it. ‘That’s me,’ he said, ‘if you’re ever in Bury St Edmunds.’ Next to the number, as an aide-memoire, he’d written: ‘The old man walking around Britain.’ And with that he was off, walking across the field in the rain, turning just once to say ‘Be happy, Mike’ with a wave of the hand, and I watched him all the way as he got into his tent and zipped up the flap.

One Man and His Bike is now available in the Caught By The River shop, priced £10.00.

To find out what other books the Caught by the River editors enjoyed this year click HERE