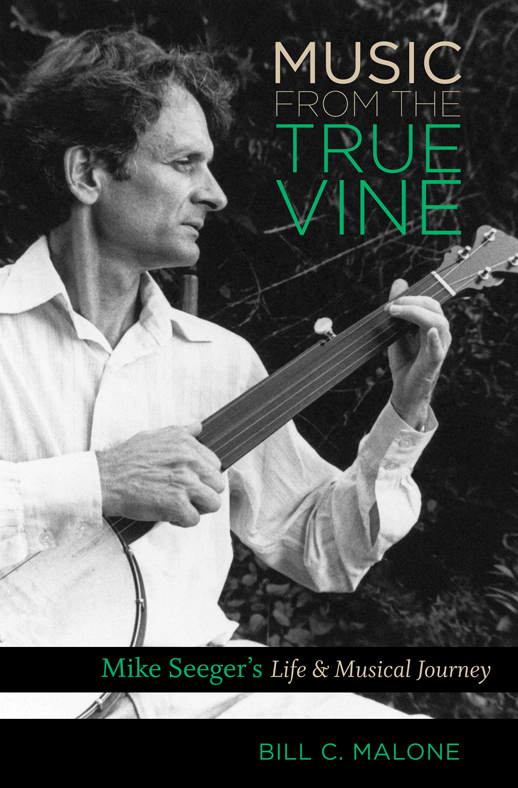

MUSIC FROM THE TRUE VINE : Mike Seeger’s Life & Musical Journey

by Bill C.Malone (The University of North Carolina Press hdbk, 235pp)

Review by Andy Childs.

As we become more familiar with the work of people like Alan Lomax*, Harry Smith and Moe Asch and their achievements in rescuing, preserving and perpetuating the roots of ‘folk’ music in its widest sense in the U.S. it becomes increasingly apparent how important that work was and how, but for the laborious scholarship and passion of these relatively few enthusiasts, the development of contemporary folk and rock music especially may have taken a completely different trajectory. It’s always amused me to think that the bloated success of the international corporate record industry with its proprietorial paranoia has been partly built on the success of artists (Bob Dylan is an obvious example) who drew much of their initial inspiration from Harry Smith’s original Anthology of American Folk Music, which was essentially a collection of bootlegs. But that’s another story. In the pantheon of heroes who toiled so hard to keep traditional music alive few were more important, and perhaps undervalued, than Mike Seeger, the subject of this engrossing and impressive biography.

As a pacifist and music scholar Mike Seeger followed in the often uncomfortable and controversial footsteps of his father Charles who was a staunch socialist and opposed America’s involvement in the Great War, political views that caused much turbulence in his career. He also introduced America’s first course in musicology at Berkeley when he taught there between 1912 and 1918 and, after devoting much of his life to classical music came to realise the social importance and musical value of ‘folk music’. So much so that he started to ‘collect’ folk songs and between 1935 and 1941 whilst working for the Federal Music Project added over 1,000 discs to the Library of Congress. His first marriage, which produced three sons, one of which was Mike’s more feted half-brother Pete, dissolved in 1929 and he went on to marry Ruth Crawford and had a further son, Mike, and three daughters including the other famous sibling Peggy.

Mike was born in Aug 1933, probably suffered from dyslexia, was a passionate cyclist, was moved about, often unhappily, from school to school as his family moved up and down market eventually settling at a school in Vermont where his inevitable absorption in music, inherited from both his parents, was allowed to flourish. He also became a conscientious objector. Ruth bought him a guitar and in 1951 he had guitar lessons from Charlie Byrd and then the more classically-inclined Sophocles Pappas, lessons that he admitted changed his life and probably made him realise that he could become an accomplished musician in his own right. A banjo was subsequently bought for Mike and Peggy to share and for tuition they both looked to older brother Pete. In his late teens Mike’s development as a musician proceeded alongside his growing passion for ‘old-time’ country and folk and its preservation. Through an intriguing character named Dick Spottswood he was introduced to the eccentric world of record collectors, a fairly exclusive group of madmen who opened Mike’s ears to a wide range of traditional music from the 20s and 30s – country music, Appalachian folk songs, hillbilly music, blues – profoundly shaping his own tastes and, subsequently, the tastes of aspiring folk singers for decades to come. He began tracking down surviving performers of this ‘old-time music’ and recording them for posterity including, most famously, Elizabeth ‘Freight Train’ Cotten who incredibly was the Seeger family’s house-keeper! Mike’s mother died in 1953 and the Seegers began to disperse, Peggy most prominently travelling around Europe until she settled in London and met Ewan McColl. Living now in the Baltimore area Mike became heavily involved in the emerging bluegrass scene there, a form of music that was often called hillbilly music and derives its name from the great Bill Monroe’s Band, The Blue Grass Boys. He befriended Hazel Dickens and started to play informally in groups with her and her brothers. He also got to know Alan Lomax, to whom he introduced new bluegrass bands and Moe Asch who, as owner of Folkways Records, asked Seeger to compile a record documenting the emerging bluegrass culture. The course of his life had been irreversibly set but it wasn’t a smooth ride by any means. He had trouble making ends meet – a failed attempt as a radio DJ was followed by a period working in what sounds like a fairly menial capacity at a recording studio in Washington – and for all his influential work over the years he never enjoyed real financial success. In 1959 he formed a group – The New Lost City Ramblers (‘the trio that changed the sound of American folk music’) – that became a major part of the rest of his life and a huge influence on a young emerging generation of musicians who looked to old-time music as a source of inspiration. Ry Cooder, Taj Mahal, Jerry Garcia, Chris Darrow, David Lindley, Bob Dylan**, Clarence White, David Grisman and John Hartford are just a few of the names who revered Seeger and his cohorts Tom Paley and John Cohen. They played the Newport Folk Festival in 1959 and soon after the Ramblers became a full-time gig. A residency at The Ash Grove in L.A. cemented their influence on the west coast and they spent a prolonged period touring U.S. universities, folk clubs, festivals and eventually, in Sept 1965, made it to our shores where they played their first gig, appropriately, at Cecil Sharp House. As Malone emphasises in this book though, Mike Seeger was a supreme multi-tasker so while engaged in a full-time career with the New Lost City Ramblers, a career which incidentally lasted on and off until a year before his death, he was still fully involved in his work promoting the legacy of the music he loved. He sat on the board of directors of several folk festivals, he lectured on the origins of the music he played, continued to record important old-time artists for posterity and also found time to make his own records, themselves homages to his beloved music. Not surprisingly this all eventually took a toll on his health, both mentally and physically. His mental problems (depression?) are only really hinted at here and the effects this had on his seemingly chaotic personal life (he was married three times) are never fully explored. What is documented is that he suffered from scoliosis (a curving of the spine from side to side) for most of his adult life and in 2001 he was diagnosed with the most “manageable” form of lymphoma which he lived with for another 8 years or so until he fell victim to a more aggressive type of blood cancer in 2009 and died later that year. There was much more in his life though that this book relates with a growing sense of awe and respect. His teaching work was critical as was his tireless efforts at preservation and documentation. But perhaps his most enduring, crucial, and entertaining work was as a musician with The New Lost City Ramblers. It’s because Mike Seeger was such an accomplished musician, such a respectful and imaginative interpreter of old-time musical traditions, and such a great performer that we was able to connect to successive younger generations and influence them so profoundly.

This book, abundant in its use of resources and obviously meticulously researched (over 40 pages of source notes and references), makes an overwhelming case for a radical evaluation of Mike Seeger’s legacy for those of us who never knew him, saw him or perhaps have even heard him. It’s an academic study, as you would expect from a Professor of History, often dry in style but not without a sense of drama and passion at crucial moments. I did finish reading it though feeling that I hadn’t fully engaged with Mike Seeger the man, the husband, the father, the charming but sometimes difficult personality, and in that respect it’s not what I would call a fully-rounded biography. What it certainly is though is a thorough and fitting account of Seeger’s work and a celebration of the timeless music that he cherished and did so much to perpetuate.

* Be sure to read John Szwed’s wonderful and revealing recent biography of Lomax – ‘The Man Who Recorded the World”.

** Dylan includes “eccentric endorsements” of Mike Seeger in ‘Chronicles’.

Not So Much A Book, More A Sizeable Chunk Of Your Life

BYRDS : Requiem For The Timeless Volume 1

by Johnny Rogan (Rogan House hdbk 1,200 pp)

When I was first presented with this colossal tome I believe I uttered an involuntary gasp of delight before a certain indefinable numbness set in and my eyes glazed over involuntarily. And as I struggled lopsidedly around town for the rest of the day and evening with it, showing it to aghast acquaintances, my initial enthusiasm for it diminished exponentially. Most books I have of this size (and apart from a few encyclopaedias this is the fattest book I think I own) are doomed to remain on my creaking shelves gathering dust. But then I thought : this is different. This is The Byrds. One of the greatest groups ever. And it’s by Johnny Rogan, heroic biographer and self-publisher. It had to be read. But this is a feast of a book and not to be digested too quickly. So I’m devouring it at 100 pages a time and intend to report back in monthly instalments. So….we start in 1965, arguably the greatest year in pop history and the scene is set for the author’s introduction to The Byrds and the beginnings of the band. Potted early histories of McGuinn, Gene Clark and Crosby (curiously Hillman and Michael Clarke weren’t considered proper members of the group at first); The Jet Set; Preflyte; manager Jim Dickson (great story about him decking Chris Hillman and a more revealing one about how he coerced Dylan into persuading the band that they should record ‘Mr.Tambourine Man’; Miles Davis remarking to a CBS bigwig that they should sign The Byrds; the recording of ‘Mr.Tambourine Man’ – 22 takes with only McGuinn actually playing on it (Clark and Crosby provided vocals); legendary publicist Derek Taylor’s involvement; and their breakthrough residency at Ciro’s in L.A. All this is engagingly told with some of Rogan’s personal reminiscences woven in, which augers well for the rest of the book. I sense that the remaining 1,100 pages will fly by and leave me gasping for volume two which apparently will be a mere 900 pages long. Bring it on! More next month.

Almost As Good As A Book

The annual Southern Music issue of Oxford American has been available since December so I hope there are still copies left if you haven’t already bought one. It’s simply the best music magazine by a country mile and essential reading. This year’s issue focuses on the state of Mississippi and comes, as usual, with a CD that will refresh the most jaded ears. Order direct from them HERE.

Next Month……..’Fings Ain’t Wot They Used T’Be : The Lionel Bart Story’ by David & Caroline Stafford – very funny and poignant. Listening to it serialised as Radio 4’s ‘Book of the Week’ recently made me want to read it a second time. Preston Lauterbach’s ‘The Chitlin’ Circuit And The Road To Rock’n’Roll’ (highly recommended by Geoff Travis),and ‘All The Madmen’ by Clinton Heylin.

Previous Bulletins can be found HERE and the Music Book Reader lives HERE.