John Niven pays tribute to Levon Helm:

‘Virgil Caine is the name…’

It is tempting to begin with something like ‘the last of The Band’s great trio of voices was silenced last week with the death of drummer and vocalist Levon Helm.’ Tempting, but not quite true: Helm’s voice as we knew it – the voice that roared defeat and defiance on the chorus of ‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down’, that sounded like it’d come straight from the creek bed on ‘Ain’t No More Cane’ – had been effectively silenced by throat cancer in the late 1990s. Something more ineffable than a wonderful, unique voice was lost last week however, when Helm finally succumbed to cancer at the age of 71. We lost a great part of what has come to be called ‘Americana’, but which you might with as much force simply call ‘America.’

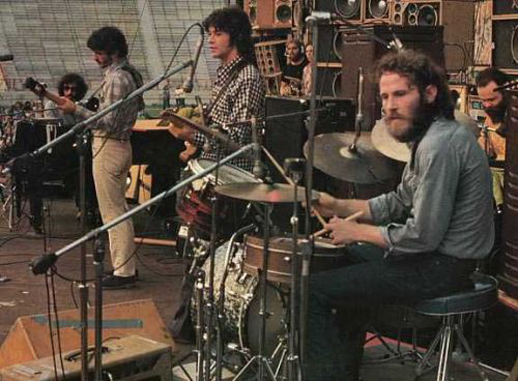

I was perhaps 13 or 14 years old the first time I saw Levon Helm. I had no idea who he was of course. My father was watching a late night screening of The Last Waltz on British TV. My father was as unaware of The Band’s music as I was. He was an insomniac and it must simply have been the only thing that was on. I remember two things: the great hall of Winterland with the chandeliers glowing in the vast blackness above the audience and the fact that the drummer was singing. Levon Helm. I’d never seen a drummer singing before. The way he leaned back into the mike and flipped the snare hand out of the way of the hi-hat hand transfixed me that night as a child as it transfixes me still.

I went about my teenage years – the fag end of punk rock in provincial Scotland – and thought no more about The Band or Levon Helm until almost a decade later. I was 21 in 1987 when I knowingly heard Levon’s voice for the first time, when Bill Prince played me The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down. We were sitting in his living room in Leytonstone, East London and we were on acid at the time. The hallucinogen presented the music in such aspic clarity that it felt like The Band were in the room, like you could hear the wood creaking in Sammy Davis Jnr’s poolhouse where they recorded the song. To paraphrase Jon Savage on The Clash, within thirty seconds I was transfixed, within a minute changed forever. Indeed, after The Clash and The Smiths, The Band became the third great musical love of my life.

And an unfashionable kind of love it was too throughout the eighties and much of the nineties. If the maxim is true that buildings reach their most dangerous period of neglect, are at their least loved nadir, after 70 years, we might say the same is true of rock music around ten to fifteen years after its peak creation. (The confused and unloved Weller and Strummer of the late eighties and early nineties for instance.) If The Band’s stock was at an all time low by the mid 80s then everything changed at the end of the following decade. For here came Mercury Rev, and Ryan Adams and Lambchop and suddenly The Band was an achingly hip name to drop, something that instantly connected you to the heart of Real American Music.

Of course, by this time the group itself had long since checked out, lost in the late seventies in a dysfunctional miasma of drugs, alcohol, egos and publishing rows. By early 2004 I had left the music industry myself and was taking the first steps towards becoming a novelist. I pitched an idea to David Barker, editor at Continuum Books in New York, for his 33 1/3 series – short books that looked in microscopic detail at the making of great albums. I proposed a slightly different approach: a novella, a work of fiction that saw the creation of The Band’s debut album Music From Big Pink through the eyes of a minor drug dealer who lived on the fringes of their circle on Woodstock. David took a chance and commissioned the book, and I will forever owe him an unknowable debt.

I spent a year writing the novella, a year immersed in as much of The Band’s lives, personalities and music as was possible, plagued and beset the whole time by all the usual difficulties of creation, but with the added pressure of dreadful responsibility – these were real people, several of whom were still alive, all of whom had families, children, friends. In the end, in terms of depicting the lives and appetites of the members of The Band, I leant towards the Johnsonian aphorism – ‘They discourse like angels, but they live like men.’

And in my mind, all the time I was writing the book, I wondered what some of its central characters would make of it if they ever read it. A couple of years after publication I received an email from Alexandria Robertson, daughter of Robbie and now an A&R executive at Warners. She’d loved the book and was kind enough to write and let me know, but it was her postscript that blew my mind – ‘My father happened to read the book and thought it was fantastic.’ Later still Alexandria and I had lunch in Los Angeles where she told me that Robbie had added, ‘Was that guy in the room?’ I pretty much floated through the rest of the day.

And now the film rights have been sold and the screenplay written by the playwright Jez Butterworth, the man behind Jerusalem. When I read Jez’s (brilliant) script it came as no surprise to me that the voice he’d chosen to open the film with, the first voice you heard, was Levon Helm’s, talking hard and raw in a Florida motel room at dawn on a cold winter morning in 1986, the morning, we quickly realize, when The Band’s high-wire falsetto singer and pianist Richard Manuel decides to take his own life.

The second of The Band’s voices to leave was bassist Rick Danko, dead of drug-related heart failure in 1999, at the age of 56. And now Levon, the bottom-end component of that harmony group within a group, its final element, is gone too.

But not dead, of course. For, regardless of whatever God you do or do not believe in, they are truly immortal, the writers and musicians who create with such force and conviction. Go to your bookcase or your record shelves and there are they – sleeplessly, eternally available, to soothe you, to thrill you, to ease you through the heartbreak headed your way, to transport you. You slip the headphones on, click on ‘PLAY’, the chords begin their sad, graceful descent from A minor and Helm states plaintively that ‘Virgil Caine is the name, and I served on the Danville train’. So effectively is the listener seduced that within one line you believe Helm is the character. (A technique purloined and later used to great effect by Bruce Springsteen.) And you are right there with him every step of the way, breathing the same cold air as that young Confederate soldier, ragged and starving as he flees Stoneman’s cavalry after the battle at Appomattox in the early spring of 1865.

Humanity, characterization, the personal blended with the sweep of history and strung across an aching melody. This is art, at its fullest, most confident pitch.

Thank you, Levon Helm.

Levon Helm, born May 26, 1940; died April 19, 2012.