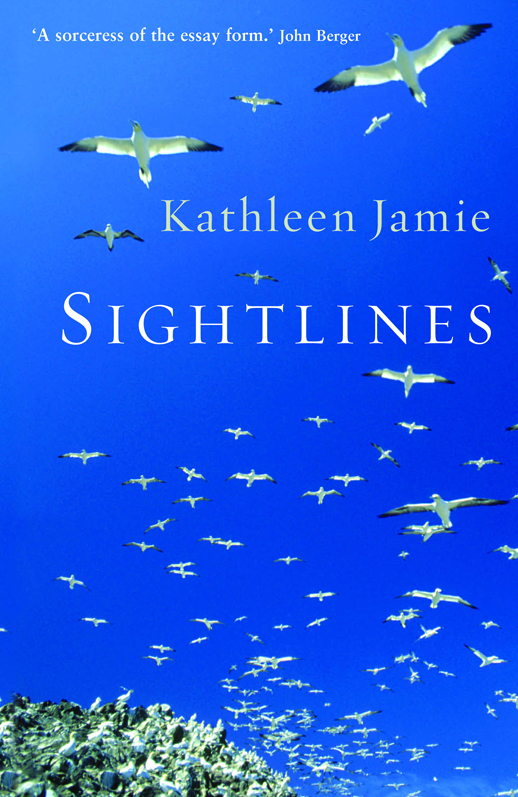

Sightlines by Kathleen Jamie

A review by Melissa Harrison

Seven years ago the award-winning Scottish poet Kathleen Jamie published Findings, a collection of minutely observed essays about the natural world, to unexpected, though richly deserved, acclaim. There turned out to be a market for quiet, contemplative writing about landscape, and since then, British nature writing has undergone a resurgence: Robert Macfarlane’s Wild Places and Roger Deakin’s Wildwood and posthumous Notes from Walnut Tree Farm came soon after, followed by reprint after reprint of old classics – Nan Shepherd, Collis, Jefferies – as well as monographs on birds, trees, weeds and wildflowers, and dozens of collections of writing about the countryside. Yet for all the ways in which the market may have grown and changed since then, Sightlines is just as quiet and spare a collection as Findings, and with the same dizzying shifts of focus that characterise Jamie’s unique perspective on the natural world.

‘It was disquieting, to be aware all the time of satellites prowling unseen above the sky, while examining a landscape others had left behind.’ Jamie – whose MA in philosophy is evident in every piece she writes – has joined a party of surveyors at work on the tiny archipelago of St Kilda in the Outer Hebrides (islands fascinate her, as do seabirds, archaeology, whales and the strange inner landscapes of human pathology). The St Kilda team are mapping cleits, the stone sheds that dot the islands in their thousands, using GPS. ‘The surveyors… were like priests,’ she says, ‘giving each of these little buildings the last rites.’ And in those two images she shows us the island – already an extraordinary place with its abandoned village, unique social history and vast seabird colonies – ministered to by modern-day divines with all their arcane equipment and watched over by invisibly orbiting machines. It’s extraordinary.

She does the same with whales, taking us to the Hvalsalen, or ‘whale hall’ in Bergen Museum, Norway. It’s a grand, nineteenth-century room hung with the bones of twenty-four whales: baleen, humpback, right, sei, blue. Killed at the height of the whaling boom, how they came to be transported to Bergen, and how they were hung in the museum, is shrouded in mystery; but they are due to be cleaned and repaired (two kilogrammes of dust are removed from one specimen alone) and Jamie returns to help with the work, making connections both philosophical and deeply personal – for instance, that the bones are still emitting the whale oil that they were hunted and killed for, and that it smells, heartbreakingly, of the wax crayons she remembers from school. ‘You could sit within the blue whale… and imagine this was your body, moving through the ocean. You could begin to imagine what it might feel like to be a blue whale.’ But running through the piece is a vein of intense sadness – and anger. ‘On a central pillar, neatly painted in Norwegian and English, were the words “Do not touch the animals”, but it was a bit late for that… Sometimes our species beggars belief,’ she says. For she is fascinated by whales: killer whales speeding through the sea off the Scottish Islands: whale vertebra on beaches, whale jawbones set up as arches, monuments, in Edinburgh, Whitby, Caithness, the island of Lewis and North Berwick. They are a totem species, and rightly so: immense, mysterious, speaking to us of another world, another time.

There are shorter pieces here, too: about a lunar eclipse, a cave, about a dead storm petrel and the way the light changes in February. In each case the subject is the starting point for a meditation on the natural world, how it persists through time, how it intersects with us, how we can imagine our place in it. And as in Findings, the natural world extends inside us, too: to the mysterious habitats of the body, its ecosystems and processes. Not long after her mother’s death Jamie attends a conference in which ‘nature’ is discussed; afterwards she finds herself thinking how ‘there are other species, not dolphins arching clear from the water, but the bacteria that can pull the rug from under us.’ At Ninewells Hospital in Dundee she attends a post-mortem, observes cells dividing and describes how helicobacter pylori look like musk oxen grazing on tundra. Looking at a liver under a microscope, she says, ‘There was an estuary, with a north bank and a south. In the estuary were… sandbanks, as if it was low tide. it was astonishing, a map of the familiar.’ Later, she drives home along the river. ‘The tide was in, no sandbanks,’ she says. ‘The inner body, plumbing and landscapes and bacteria. The other world also had flown open like a door, and I wondered as I drove, and I wonder still, what is it that we’re just not seeing?’

Sightlines is an act of seeing: not just of observation, of looking and noticing – though Jamie is an accomplished noticer – but of intellectual and imaginative seeing, of chasing down connections, teasing out similarities and slowly, patiently, allowing each subject to come into view. To call it ‘nature writing’ is to tell only part of the story; these are meditations on the world and our place in it: on what we’ve done, who we’ve been and where we can go from here.

In Findings and Sightlines Kathleen Jamie has carved out a niche that’s both deeply personal and broadly philosophical, in prose that seems to move naturally from sparse to lyrical and back. These essays ask the big questions quietly, and are all the more powerful for it.

Melissa Harrison is writer and photographer who lives in South London and blogs about the city’s wild, forgotten corners at talesofthecity.co.uk. Her short story, Dimmity, won the John Muir Trust’s ‘Wild Writing’ award for 2010 [link: http://www.jmt.org/wild-writing2010.asp#Dimmity] and her first novel, Clay, will be published by Bloomsbury in January 2013. Follow her on Twitter: @M_Z_Harrison

Sightlines, is now on sale from the Caught by the River shop, priced £8.99