A review by Rob St. John.

Last year, American ecologist Bryan Pijanowski and colleagues proposed a novel new area of environmental research: soundscape ecology. By collecting and collating masses of acoustic recordings of an ecosystem – whether birdsong, animal calls, wind, water or human-made sound – Pijanowski proposed that an assessment of the ecosystem’s health might be made.

The idea of a ‘soundscape’ was developed by Canadian composer and environmentalist R Murray Schafer to encompass the range and variety of sounds recorded in a landscape. In addition to potentially indicating an ecosystem’s health, soundscapes provide a powerful acoustic link between humans and nature, an often-unnoticed sonic web that can evoke deep connections to place, people and memory. However, the quietly quickening creep of biodiversity loss and noise pollution is increasingly eroding our auditory connection with nature.

As sound is inherently fleeting and ephemeral, changes to natural soundscapes may lead to ‘extinctions of experience’, where our interactions with rich, diverse soundscapes are slowly severed. In addition, we generally only recognise and understand the sonic landscapes that we experience, which can lead to a phenomenon that ecologists call ‘shifting baseline syndrome’ where each new generation accepts a more degraded state of the environment than those that have gone before.

It is this creeping and often unnoticed slide in the diversity and ‘health’ of global soundscapes that concerns Pijanowski. The changes to natural soundscapes caused by human activity is not only changing the sound signature of ecosystems, but also actively affecting the health of the biodiversity they contain. Animal communication, mating calls, alarm calls and the ability to detect predators and prey are all potentially compromised by sound pollution. Studies have shown that some birds actively change their song to cope with the auditory mess created by human landscapes, yet this is not possible for all species, some of which will become unable to survive in certain highly altered landscapes. The new field of soundscape ecology looks to document, scientifically analyse and take conservation action for the ‘health’ of global soundscapes.

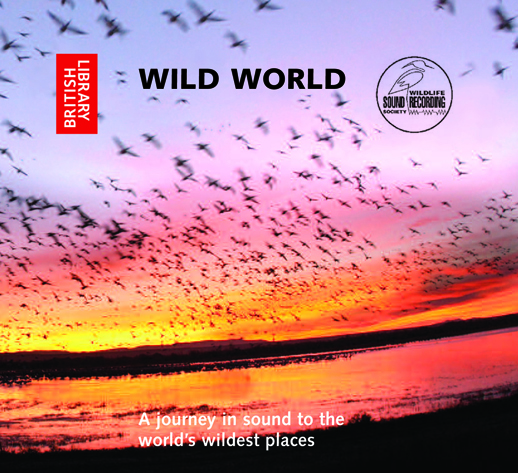

In this context comes Wild World , a new set of soundscape recordings released by The British Library. Wild World documents the soundscapes of 22 global ecosystems across 140 minutes of consistently clear and detailed audio recordings made by of members of the Wildlife Sound Recording Society. Two of the most interesting are featured on the second CD. In Analamazaotra, Madagascar, the common newtonia, velvet asity and strip-throated jery combine to create some Arvo Pärt-esq atonal hymnal, dripping with the atmosphere of the damp forest. Similarly, the plaintive call of the common loon echoing around the Twin Lakes of Ontario, Canada is magical. Interspersed with the splash of jumping fish and the croak of a raven, you are immersed in what I imagine to be a cold, crystalline lakeside dawn encircled by rising mist.

[audio:https://www.caughtbytheriver.net//wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Twin-Lakes_Ontario_Canada_British-Library.mp3|titles=Twin Lakes_Ontario_Canada_British Library]

And for me, this is the value of these recordings. Not only do they give snippets of the diverse, lively global ecosystems studied by Bryan Pijanowski and colleagues, they also inspire you to actively listen and imagine. Increasingly, I move through the city trying my best not to actively listen to the landscape, instead to block out ambient noise. Perhaps it’s slightly ironic that many people will listen to these recordings through headphones as they travel around, blocking out their own soundscape in favour of these immersive minimals. Regardless, this high quality set of recordings provide a sampler of a range of diverse, interesting global soundscapes, forming a timely and inspiring reminder to actively listen to our environments and perhaps value, understand and imagine them new ways.

Buy Wild World