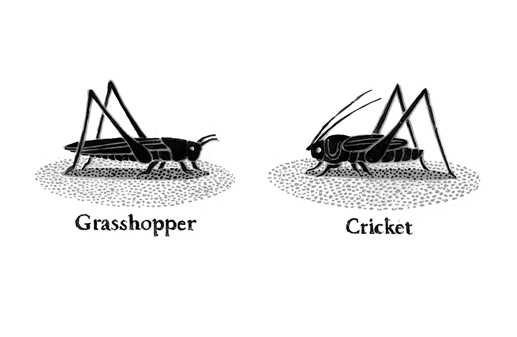

Illustration by Jon McNaught.

Illustration by Jon McNaught.

Cheryl Tipp on the summertime sounds of stridulating insects:

I’m probably speaking too soon, but it looks as if summer is finally gracing us with its presence. One sound that screams “summer!” to me is the gentle purring of stridulating insects. Not birdsong, not the civilised slap of leather on willow, but the simple sound of a churring grasshopper revelling in the heat of a summer’s day. This is a sound that comes from my childhood and will be forever filled with memories of driving down to the south coast, windows wide open with mum, dad, brother and the family dog (mind you, this also reminds me of my brother being carsick but let’s skim over that shall we).

Insects tend to be overshadowed by the ruling might of birdsong; who would pay attention to the humble Field Cricket when you have a Nightingale belting out tune after tune? In some respects, this is a fair comment – birdsong offers a lot more diversity when it comes to content and composition – but let’s not dismiss the appeal of insect sounds too soon.

There seems to be a growing appreciation in field recording circles for producing publications based on insect sounds. I’m not talking about the sterile world of identification guides here; I’m talking about publications that have no purpose other than to provide an enjoyable listening experience. Hiroki Sasajima’s excellent release ‘Colony’ is just one example of somebody recognising the beauty of insect sounds and wanting to share this with the world. This album is freely available through the rather marvellous netlabel Impulsive Habitat and focuses purely on natural soundscapes dominated by communicating insects. All were recorded at locations across Japan and really showcase the beauty and diversity of this slice of the animal kingdom.

Insects are able to produce sounds using a range of different methods. Take crickets as an example – these miniature musicians communicate by striking a plectrum-like structure found on one wing against a flat file located on the adjacent wing. Then you’ve got the method of tymbal vibration – this just sounds cool don’t you think? Cicadas are the lucky chaps who get to use this technique. Tymbals are basically membranes stretched across each side of the insect’s abdomen that vibrate rapidly during muscle contractions. Adjacent air sacs act as resonance chambers, thereby amplifying the sound produced by this vibration. I guess you could think of a cicada’s body as a bit like a recording studio – the tymbals are the band while the air sacs are the sound engineers, working their magic to improve the original performance for the maximum impact.

As with birdsong, most insects use sound to defend territories and attract a mate. And there are the sounds, such as wingbeats, that are audio by products of non-communicative processes. These can be just as evocative however – just think of the gentle buzzing of bees in a blossoming garden. That’s a signature sound of summer if ever there was one.

Beauty is definitely in the eye of the beholder, but to most of us, insects aren’t the most attractive residents on planet earth. At least when thinking in terms of the visual. Look beyond this however and you’ll discover a wonderful world full of rhythmic patterns and soothing sounds that go very well with a glass of Pimms!