Two new projects (Landmarks and Landreader) are underway that aim to gather, celebrate and conserve the rich but threatened lexicon of place that has covered the British landscape with language as deep and as nourishing as any soil for thousands of years. Tim Dee is interested.

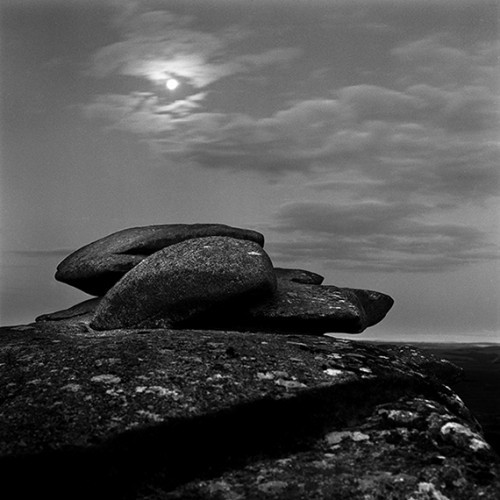

Cornubian Batholith © Dominick Tyler 2013

Cornubian Batholith © Dominick Tyler 2013

Common names are important. Because there were no people around at the time of the dinosaurs to describe the animals in words that spoke of them, we only have scientific names applied posthumously to the fossil eggs and bones that have been found since their extinction. Dinosaurs, in consequence, are doing time locked in their Latin binomials. There were no Maoris to call them moa, no Dutch sailors to talk of dodos.

Dinosaurs are also trapped in the monochrome tar-pit of the era of their unearthing. I remember my shock at the relatively recent discovery of fossilised dinosaur skin and the way it lifted the animals into colour for the first time in my life. Because everything about them that I had previously consumed had been in black and white (even Jurassic Park paints its monsters with a cautiously bleached palette), I hadn’t space on my retina for a terrible lizard as bright as an arrow poison frog.

The moa and the dodo fare a little better in our mind’s eye but they too are fixed by the language of their describers. Suppose that somewhere on the islands of the Mascarenes, like an unsurrendered Japanese soldier walking out of the forests of Burma, a dodo was found quietly getting on with its life. What would that discovery do to our imaginations? How might we think the dodo now? How could the gone become the here? All the living words we have for dodos, all the words spoken and written by those who saw them, are hundreds of years old, so the bird shifts in our heads with the language. It creaks with age. And all extinctions and losses, every one entwined with language, as they must be, will be like this.

Not a single bird knows it’s a bird, of course, not one tree. No dodo cared to be a dodo. Likewise, no landmark needs its name. Gaping gill couldn’t give a toss. But without a name made in our mouths, an animal or a place struggles to find any purchase in our minds or our hearts. One of the jobs of poets, Shakespeare said, was to give ‘a local habitation and a name’ to the products of the human imagination. Our species has been doing the same to the entire world beyond the human ever since we stepped into consciousness and away from the wilder swirl of life. We have been incarnating, bodying forth in language, everything that is other. So it is that nature writing isn’t nature’s writing but helps nonetheless to make it intelligible and felt.

But sometimes the words get lost. When Daniel Defoe travelled the country to write his great Tour in the early eighteenth century he visited, or tried to visit, the old Roman town of Ancaster on the fen edge in Lincolnshire thinking it would afford a ‘great subject of discourse’ but the place had gone and no one knew about the town, it had ‘sunk’ Defoe says, ‘out of knowledge’. Mapped only as a ruin and buried in time it couldn’t speak and so was passed over.

Some forms of life are so marginal to our perception that they do not sink out of knowledge because they have never risen to its surface. Mark Cocker ends his marvellous compendium of writings from his home parish in Norfolk, Claxton, (due from Cape in October) with a list of all the non-human species he has found there. Only a handful of his hoverflies have a common name (one, superbly, is called inane, other English names he admits to making up himself). Painstaking identification with hand-lenses and expert textbooks focused the animals down to species level and a Latin name but there the encounter had to stop. Most hoverflies have never been known enough to come into English. They have no ‘human dossier’ as Geoffrey Grigson called the pressing accumulation of intimacy and association that lies behind common naming.

When he was writing his Flora Britannica (1996) Richard Mabey solicited new names as well as stories about plants in the hope that, even as wild flowers were disappearing and human lives were increasingly spent indoors or screen-mediated, the old impulses (local names for local things) were surviving. He found a ‘lively popular culture of plants’ to match and modernise if not quite equal the great lists of local names that Geoffrey Grigson had harvested from centuries of botanical history for his Englishman’s Flora (1958). Mark Cocker did the same in his Birds Britannica (2005) building on Francesca Greenoak’s All the Birds of the Air (1979). I have always enjoyed and encouraged the Chiswick Flyover as a new-minted name for a pied wagtail, capturing, as it does, the bird’s call, jizz and urban adaptations, but I don’t think it has found much traction in the world at large.

Calling names remains a human trait. Language is a virus endemic to our species. We cannot shut it down or shake it off. The Knowledge is what we live by and it is infectious. Books that are a far cry from field guides have had much to say about this too. Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker (1980), Will Self’s Book of Dave (2006), even Clive King’s Stig of the Dump (1963), have made and remade argots and turned them into languages of value, argosies brought back to us from their dystopic and time shifted worlds, new words to describe new places. Riddley Walker talks of the ‘Puter Leat’ or the computer elite, those who lived before the apocalypse that is the starting point for Hoban’s novel: ‘we had the woal worl in our mynd and we had worls beyont this in our mynd’. Will Self’s book comes with an glossary: a ‘blackwing’ is a gannet, an ‘oilgull’ is (close to accurately) a fulmar, a ‘bonkergulls’ a great skua (perhaps Dave has picked up a ghost trace of bonxie, the Shetlandic name for the heavy and dog-food brown piratical bird that is commonly used by birdwatchers), ‘fireweed’ is rosebay willow-herb (as it has been called before), a ‘chrissyleaf’ is holly, and a ‘dashboard’, wonderfully, is the Milky Way, a ‘headlight’ which can be full-beam or dipped and so on, is the moon.

Some inventions work back here on our earth as it is now, but some will not last and some of the old names and words will go when they no longer stick. Usage is all. With red-backed shrikes no longer impaling their prey on thorns in the British countryside the butcher-bird has backed out of our minds (though there are ghosts still abroad and Nick Cave sings of one on Babe, You Turn Me On, drawing, I suspect, on his Australian memories, where there are other prickly customers).

Adjacent to the naming and renaming of a species in its home territory or habitat is the naming of the place itself and this is the concern of Robert Macfarlane and Dominick Tyler in their two, related and simultaneous, projects that reach out towards a kind of national linguistic ground sourcing. The mental maps of places we know, which we draw in language, are of great importance to us. We’d be lost in all sorts of ways without them.

Dwelling and unhomelyness has been a preoccupation for many western philosophers in the last hundred years, as it has got harder for us to feel at home, to both map and live in our lives. And most of us are living and working now in places that are not really places, that struggle to be distinctive or local enough to warrant their own common names, names that might grow up out of a place and get rubbed and scuffed over time and with use. I described the A14 as a place that is not really a place but where I partly live in Four Fields; likewise, what is the topos or essence of place of Heathrow say, compared to Gatwick, or the Bluewater shopping centre compared to Cribbs Causeway; where, indeed, does the Internet reside other than at that most fittingly strange address at Infinite Loop, Cupertino?

Pitched against all this, a kind of rescue archaeology is underway in these two projects, a gathering of lovely facts and human truths ahead of a feared time (‘Emtwenny5’ time, in The Book of Dave) when some blander more generic mix might be poured mentally into our skulls and physically across our landscapes. Both will result in a book and both will be built around glossaries (one perhaps mostly photographic, the other more linguistic).

Robert Macfarlane’s book is called Landmarks and is due next year (from Penguin). He describes it as a ‘field-guide and a word-hoard’, and its subject is language and landscape, language-for-landscape. Macfarlane’s book has grown out of his long 2010 essay called ‘The Counter-Desecration Phrasebook’, which was itself inspired by a ‘Peat Glossary’ drawn up in 2007 by two friends of his on the Isle of Lewis, recording the astonishing range and poetry of Gaelic terms for peat and moorland specific to the island. Landmarks will comprise nine chapter-essays, and eight accompanying glossaries that gather 3000+ words from the ‘remarkable lexis for landscape (weather, landform, phenomenon, landmark) that exists in these islands, and the wealth of which has been millennia in the riching.’ The glossaries are intended to be celebrations of diversity and arrival, drawing from scores of languages and dialects ancient and contemporary, from Old Norse through to modern Shetlandic, from Anglo-Saxon through Bengali and Romani to last-year’s coinages of children in a Cambridgeshire primary school. The chapters will explore writing and language-use and ways of looking so fierce in their focus that, Macfarlane hopes, they might ‘change the vision of its readers for good, in both senses.’ The book is to be about both how we ‘landmark and are landmarked.’

Gaping Gill © Dominick Tyler 2014

Gaping Gill © Dominick Tyler 2014

Dominick Tyler is a photographer who got interested in this same subject when he went to take pictures for a book about wild swimming and realized he had only an impoverished and ‘woefully inadequate’ vocabulary to describe the places where he was taking photographs. Sensing some deficit, he began collecting words for landscape features, ‘words like jackstraw, zawn, clitter and logan, cowbelly, hum and corrie, spinney, karst and tor.’ Tyler’s collection continues and is taking various forms. A book (from Guardian Faber) of photographs and words is due next year and the project which is called Landreader has a website which encourages contributions in a mix of crowd sourcing and citizen science.

Macfarlane and Tyler both acknowledge that they will not be the first in the field. The charity Common Ground has been agitating in this area since 1985. In the US, Barry Lopez and Debra Gwartney edited a compendium called Home Ground: Language for an American Landscape (2011). Another guiding light is the extraordinary work of Tim Robinson in western Ireland. He has spent decades there writing and mapping the land, recording human occupation and meaning through names to an astonishing depth, until his pages and papers are almost, to my mind, suffocatingly thick with marks. Over a longer period and in a somewhat quieter mode, the English Place-Name Society (founded in 1923 and still at work) has been doing something similar. Their publications are extraordinary poems of place. The list of individual field names in the Cambridgeshire volume pretty much took the top off my head when I found it in a second-hand shop in the city and I kept the book at my side as I was writing Four Fields. There have been other mind-blowing encyclopaedic works like Margaret Gelling’s Place Names in the Landscape (1984) and more recently other parts of the academy have got interested as cultural and psycho-geographers have done their own version of a mass trespass across the country. There is room for everyone. Access and common ground is what it is all about. The more voices there are trying out their words against the places they are naming then the longer this joining of human nature (it being in our nature to name) with what Thoreau called the ‘hard matter’ of the irreducible world will endure.

So long as the places remain and the names we have given them carry on being operative, we might continue to be able to ‘lie down in the word-hoard’ as Seamus Heaney put it in his poem North, or take shelter in the land or make a home in it from the way that we have brought it into language. Bivouac in words. After one of his shipwreckings in the Odyssey, Odysseus clambers up a hill from a beach and crawls beneath two olive trees, one wild, and one domesticated, and makes a nest there from the dropped leaves of both. Coleridge similarly, walking the Lake District in June 1801 found ‘a Hollow place in a Rock like a Coffin – exactly my own Length – there I lay and slept. It was quite soft.’

———————————————————————————————————————

Tim Dee is the author of The Running Sky (2009) and Four Fields (in Vintage paperback in August). He is talking to Will Atkins about his book The Moor and about Four Fields in two events on the Caught by the River stage at the Port Eliot festival in July.