by David Callahan

Bloomsbury, 224 pages, hardcover, out now

Review by Roy Wilkinson

Assembling a history of birdwatching with reference only to birds would be like documenting pop music purely with chart positions, or narrating the life and times of football solely with final scores. All three areas are, of course, full of human congress – social histories that can be tracked via artefacts and technological innovation. Author David Callahan is well placed to understand the places where science and leisure meet. As well as being a staff writer at Birdwatch magazine Callahan is frontman with indie band The Wolfhounds. Stemming from mid-1980s Romford, The Wolfhounds maybe bear the same relation to The Fall as the junior offshoot the Young Ornithologists Club once did to the RSPB. Certainly the YOC’s stark, slightly menacing kestrel badge – a Proustian item for birdwatchers of a certain age – is one of the artefacts that Callahan and his editor/co-writer Dominic Mitchell artfully deploy in this book.

The material traces of football and pop have long been recognised as secular variants on the religious relic. See Elvis’s gold lamé suit as photographed by Albert Watson – in solemn isolation on a coathanger. Or the way the Spanish footballer Andoni Goikoetxea took the boot he’d used to wreck Diego Maradona’s ankle ligaments and preserved it in a glass case. Some of the items in this book have a literally religious aspect – the 1505 Raphael painting Madonna of the Goldfinch, tomb paintings of red-breasted geese from Ancient Egypt. The latter are the earliest known image in which birds can be clearly identified as a particular species.

Coming after the BBC Radio 4 series A History Of The World in 100 Objects, this book can’t claim to be an original idea, but it’s still a good one. The 100 chosen birdwatching artefacts are all presented across a simple, elegant spread. The objects glow on the page – whether an RSPB membership card from 1889 or a Swarovski ATX modular telescope (a Rolls Royce of birdwatching optics). The degree of historical resonance is nicely vast. The prehistoric rock painting of extinct flightless birds may be as much as 45,000 years old. Big Jake Calls The Waders is from 1980 – a vinyl LP on which birder Jake Ward does his curlew impressions (as the book’s authors note, Ward’s beard and knitted hat giving him the bearing of a prog-rock Percy Thrower).

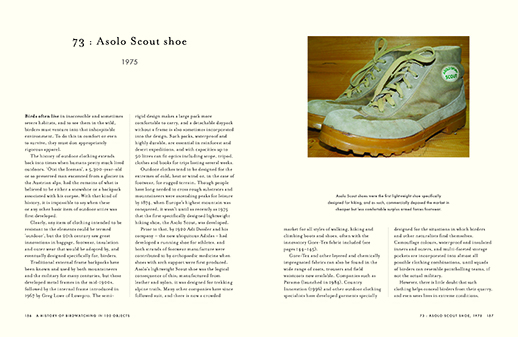

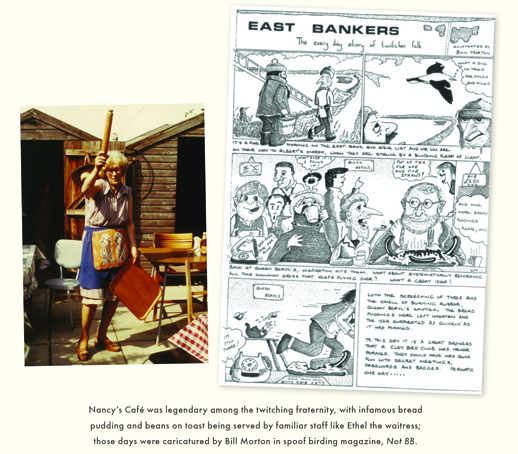

The book’s content takes us across time and space, tracking hardware and ideas. Pig-bristle paintbrushes. The Nikon Coolpix 4500. Nancy’s Cafe. Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen’s forest owlet specimen of 1880. The Asolo Scout boot from 1975 – the latter serving as a springboard into the world of outdoor apparel, from Ötzi the Iceman’s 5,000-year-old backpack onwards. Nancy’s Cafe – run by the fittingly named Nancy Gull – was a tea-and-toast spot at the celebrated British birdwatching locale of Cley-next-the-sea on the north Norfolk coast. Here was a world before mobile phones and pagers. The cafe owners tolerated a birdwatching clientele eking out cups of coffee as they waited for news to come filtering in. The phone would ring, to be answered by a cafe patron. They would invariably hear two words down the line: “Anything about?”

The entry on Meinertzhagen and his owlet leads us into the undercurrents of fraud and fantasia that run through birdwatching. To an extent, birdwatching has run on trust – particularly in the days before sightings could relatively easily be corroborated by digital images. If someone claims they’ve seen a rare bird or even one thought extinct – an ivory-billed woodpecker, an eskimo curlew – how can you have absolute certainty they haven’t? Meinertzhagen is a bewildering example of the place were birdwatching spuriousness crosses over into a weird psychological helplessness. Meinertzhagen was a wealthy and well-connected son of the British elite. He served in in the British Army as a chief of military intelligence in East Africa. He was also a globe-trotting birdwatcher who once discovered a new species of bird, the Afghan snowfinch. But he seemingly couldn’t help but import some of his spying deceptions into his birding activity. The forest owlet was considered extinct until it was rediscovered in 1997. Prior to that it was known only from seven preserved specimens from the 1880s. Meinertzhagen claimed to have collected one of these, in Gujurat in India. But there now seems little doubt he’d simply stolen his example. But that was far from the worst of it. While he was serving in India, Meinertzhagen, apparently, killed one of his assistants in a fit of rage – and then had the local police cover up the death.

By the end this book amounts to a fascinating bird-world artefact in its own right. From a Barbary falcon from ancient Egypt’s Book of the Dead to a British Birdwatching Fair poster from 1989, the 100 objects form a fascinating testimony to the hold birds have exerted on our collective consciousness. The final entry forms a speculative look to the future. Will bird migration soon be tracked via the data that can be gleaned from just man-made DNA molecules? Will legions of birdwatchers soon deploy portable DNA-tesing machines, inserting a found feather to identify the species that left it? And will these high-tech tendencies be balanced by a rise in the analogue inclinations that have long been there in pop music – with birdwatching factions casting themselves as the ornithological equivalent of cassette-only records labels, and insisting on apprehending birds with nowt but the naked eye.

A History of Birdwatching in 100 Objects is on sale in the Caught by the River shop, priced £18.00

David Callahan will be among our guests at the Branchage Festival, Jersey on Saturday 27 September. More information on that event can be found here.