Thanks to Jack Robert Sellen for this enlivened review of the autobiography of little known legend Sydney Scroggie, a war-blinded and one-legged Scottish mountain man who climbed until his dying days.

Cairngorms Scene and Unseen by Sydney Scroggie (Scottish Mountaineering Trust, 1989) (hdbk, 117 pp)

The intermittent chatter of kids on this hot first day of their summer holiday echoes about the new-builds; enters our flat, my ears, my consciousness. I pick out other constituent parts of the background noise: the soaring moan of an aeroplane, a neighbour hoovering, a train rumbling out to Kent. Eyes closed, I hear urban life, and feel it. The belltower, a favourite of Betjeman, interrupts. I look across, see the hammer fall a second time and its chime reluctantly follows. The sunshine reflected in the golden hands and numerals of the matt-black clockface beneath causes moisture to form in my tingling, blurry eyes. Wrong frame of mind. Another juvenile attempt at meditation has failed.

Vision restored, I see the clay-potted pyracantha, dwarf bamboo, and pine shrub appropriated from an office roof terrace quiver slightly in a can’t-be-arsed breeze, the small evergreen browning at the edges against the white balcony wall. The metropolitan trees in the churchyard, almost level with me at six storeys, rustle on.

I stare at the pine shrub I don’t know the name of and think about a forthcoming trip to Scotland: the ever-wild Highlands of my imagination and those briefly studded with Berghaused fairweather visitors such as myself in reality. Thoughts turn to Sydney Scroggie, the man who will not leave my mind.

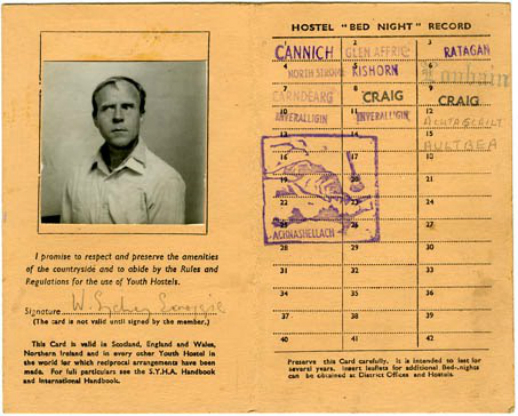

A war-blinded, tin-legged Lovat Scout, Scroggie was a true man of the hills and in his own words, an “inveterate scribbler” as poet and writer. Incredibly, despite his becoming disfigured by a mine in the Second World War he went on to complete over 600 hill climbs with companions, well into his eighties. He is most frequently quoted as saying “I can do without my eyes, but I can’t do without my mountains.”

Prompted by an episode of the excellent 1970s Weir’s Way series by Scottish Television, I’d not long ago sought out Scroggie’s autobiography, The Cairngorms Scene and Unseen, for which the jovial gnome Tom Weir also wrote the foreword. Though slim, the book is at once beautifully evocative, wry and inspirational.

Retrieving the book from semi-retirement on the shelf, I flick to the afterword, remembering that the author outlines here his life’s paradox and thinking there may be lessons to be learned from his situation with regard to my poorly-practiced mindfulness:

“I have discovered that it is not the visual side of things in the hills that constitutes the profoundest aspect of the experience, any more than it is the croak of the ptarmigan, the scent of the heather, the feel of the granite under your fingers, or any other of the merely physical phenomena which are part and parcel of the hills. What draws you there is an inner experience, something psychological, something poetic, which perhaps cannot be fully understood when the physical aspect of things gets in the way when you can see. […] I am prepared to allot only point five of one per-cent to the visual side of the hills in their power to awe and impress; the blind man is without that little amount, but the rest, and this is far more important, is as much his as to any climber, deerstalker, laird or hill shepherd. He is au fait with the heart of the matter.”

And so, the book’s vivid descriptions of Scroggie’s beloved Cairngorms and of the attraction that governs he and his friends’ fascination with them do much to reject our natural obsession with the visual. In fact, it is on occasion hard to work out whether, owing to the variegated chronology of his reminiscences, Scroggie is indeed sightless or not during the tales recounted. It becomes apparent now that that simply doesn’t matter.

The topics of discussion vary through the book as they always so effortlessly do among fellow walkers out on a long’un: his upbringing (“I was a good if careless scholar”); bothy life; ghosts; the economically essential but “undesirable” nature of tourism in Scotland; being naked in the hills in summer with pals and discovered by two dozen female students. It is however through his enjoyable discussions on the theme of anti-establishmentism that Scroggie’s astute (sometimes bordering on dogmatic) wit emerges, with an appreciation at all times for the bigger picture as much as the minutiae of life:

“It was in May, 1959, only the week after Bob did the Lairig with me, and in the early morning coolness of the Rothiemurchus Forest, Bob got a fire going to make some tea. The fact that fires are strictly prohibited in this area would be part of the charm of the thing to Bob. In a democratic society, these anonymous authorities that spring up everywhere like autumn mushrooms must not be suffered to promulgate their absurd fiats with impunity. If everyone started obeying grim notices like these in the Rothiemurchus Forest, we would all be slaves in no time. With thrill calls, tits and chaffinches seemed to approve this act of rebellion on the part of this wild and bearded figure, and even the old Scots pines, as it were, nodded indulgently as the first fragrance of woodsmoke wafted amongst them in the morning breeze. We would rather be burnt to the ground by this bold fellow, they seemed to be saying, than preserved by these damned Nature Conservancy people.”

An adversary of competitive activity, Scroggie stands up to that which, he feels, are modern artificialities at odds with his understanding of the mountains. The Duke of Edinburgh Award Scheme fails to recognise “an inner vision of truth”; the Olympics are an “even crasser quatrennial folly” and “in the Scottish hills, the lowest form of life is the skier, and I do not mean by this the resolute few who don rucksacks and planks with a view to pursuing in the winter hills those same poetical and metaphysical objectives which for some people are to be found in the hills and nowhere else.”

Those times when Scroggie was not out walking pursuing his liberating objectives, he enjoyed publishing poetry for himself and others (some of which appears throughout his autobiography), just as Ronald Blythe’s poet in Akenfield states:

“City life fragments a man. He is not complete when the reminders of the great natural complex of which he is a part are absent. The business of poetry is to mend the fragmentation which occurs when men forget their place in the natural creation.”

Given that there will have been no danger of Syd forgetting his place in the world, poetry or not, I believe therefore that his writing is a quite selfless legacy on his part.

A pigeon, the only form of avian life to care to visit our sixth-floor birdfeeder, click-clacks across the sheet metal of the balcony ledge above the little pine tree and my mind returns to the present. Do I still think it necessary to find out the name of that shrub? I remain unsure. I feel I ought to be capable of recognising and efficiently describing my earthly surroundings to such remarkable folks as Scroggie. But of course he wouldn’t really need or want me to for his sake. He’d want me to do it for myself.

I put the book down, close my eyes and the locale pervades mind; starts to inform my thoughts. The clock strikes three. Perhaps I’ll try this in the hills next time.

We have a copy of Cairngorms Scene and Unseen by Sydney Scroggie (Scottish Mountaineering Trust, 1989) (hdbk, 117 pp), to give away. To be in with a chance of getting your hands on it, please answer the following question correctly;

In which country did Scroggie lose his sight and lower leg during World War 2?

Please send your answers to info@caughtbytheriver.net by midnight Sunday 24th August.