Words and pictures by Richard Carter.

How a mere week can make a big difference in the natural world.

What a difference a week can make. When we left for North Wales, the future of the United Kingdom hung in the balance; by the time we returned home, Scotland had voted. But I’m not referring to politics; a week can also make a big difference in phenology: how the changing seasons affect the natural world we see around us.

We usually plan our Anglesey holiday for the first full week in September. Being child-free, we like to wait until everyone else’s kids are safely back at school, to ensure a bit more peace and quiet. I’ll let you into a little secret too: the weather’s nearly always better in early September than in August. But, for logistical reasons, we had to push our holiday back a week this year.

The difference was apparent even before we arrived at the farm. As we followed the main road anti-clockwise around the island, we kept remarking on how the leaves had already begun to turn on many of the trees. Some had even fallen. But the seasonal change really hit home next morning, when I took the first of my daily pre-breakfast strolls down to the rocks, to gaze out into the Irish Sea, and to think about nothing for an hour or so. I could feel the change in the air: the summer warmth was gone. It wasn’t exactly chilly, but the sun’s power was noticeably diminished. It felt half-hearted, back-endish.

I could have sworn the sun was noticeably lower in the sky too. Instead of sparkling off the sea, its rays seemed to be absorbed and dissipated by the waves. Not just the sea. The clouds weren’t their familiar, dazzling seaside white, but a diffuse, salmon pink. To add to the general feeling of pallidness, the horizon and the mountains of Snowdonia were rendered indistinct, sometimes invisible, by a faint but persistent mist that lasted all week.

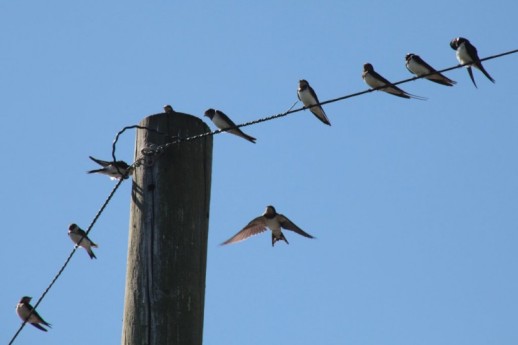

There were still gannets, gulls and guillemots, but not a single late-season tern remained patrolling offshore in search of a last feed before its long journey south. Gone, too, were most of the wheatears, martins and swallows. Usually, during our stay in Anglesey, the swallows congregate in scores on the farm’s barn roof and telegraph wires, or criss-cross the field in front of the caravan, frantically stocking up on insect fat. But just a week later, and the swallows had all gone, save for a few stragglers. Actually, no, probably not stragglers; migrants from farther north, more likely, just passing through.

How did they decide? All those birds, milling around in the sky a mere week ago, how did they come to their momentous collective decision? There was no ‘Yes’ vote, that’s for sure; no 51% saying it’s time to leave the UK, so off we all go! But gone they had. There must have been some general feeling in the air—in the blood and synapses—that it would be time to head off soon. Why else would they congregate in such numbers? But one of those birds must have been the first to embark on that long, perilous journey towards southern Africa—even though it might not have realised what it was doing at the time.

Perhaps it was like when I’m lying awake in bed some mornings, thinking it’s about time I got up, and the next thing I know, I’m out of bed and getting dressed without remembering having made any conscious decision to do so. Or perhaps it was like at the starting line in a horse race, when none of the jockeys wants to start near the back, so they mingle nervously on their mounts, press forward, possibly have one or two false starts, and suddenly they’re off! Or perhaps it was more like an avalanche, like in that wonderful James Thurber story in which some unknown citizen of Columbus, Ohio, innocently begins to run, inadvertently sending the whole of the rest of the city into a terrified stampede, in the mistaken belief that the local dam has burst.

Whatever it was that set them on their way, I hope the swallows, martins, and wheatears have a safe journey south. Their sudden absence is a sure sign that the year is now coasting towards winter. I shall anxiously await their return next spring.

In the meantime, the world moves on. One morning very soon, Orion will hang magnificent in a clear, dark sky above our gate, heralding the official start of autumn, as far as we’re concerned. There are sloes to gather. Geese will be heading our way. Fieldfares and redwings will follow. Waxwings too, if we’re lucky.

That’s the beauty of our yearly cycle: there’s always something to look forward to. Something to delight us, until the swallows return.