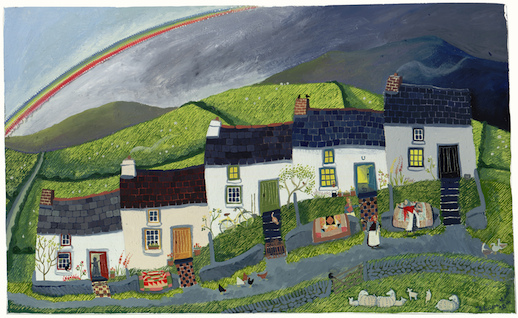

Does dim dal: Valériane Leblond.

Does dim dal: Valériane Leblond.

Today’s post, by Miriam Darlington, author of the acclaimed Otter Country, comes courtesy of Wales Arts Review. A special edition of the review – The inaugural Welsh Nature Issue – is available online today. Here’s the link. Thanks to the editors, John Lavin and Jon Gower (who most of you will know as the author of the Bardsey Island essays) for allowing us to share their content. Pay them a visit and lend them your support.

By Miriam Darlington

Round the side of the Co-op, just over the low, concrete wall where the ground drops away, you’ll see it riffling quietly between the grassy banks of a ditch. With a scattering of wrappers, old cans and tattered bags, clear, shallow and vibrant, it curves and whispers, then invites your eye into where it darkens under the road bridge. Over some shingle banks, beneath a confusion of drooping reeds and foliage, it seeps into the more robust flow of the Afon Teifi.

Here human and water-territory overlap. Beyond the amenity grassland of the townscape, these overlooked slivers of ground do not seem to belong to anyone, but amongst their shifting brambles and broken bottles are ancient otter ways, newt paths, fish ways. Just out of sight, herons watch for eels as thick as bike chains. In the dry days of summer, often they are fish paths with no fish in. But when it rains, the intricate mesh of these water veins become tadpole ways, toad marches. They are the road system for mink, vole, sea trout and salmon parr. By definition meandering, shifting, fluid, flanked by hart’s tongue fern and mosses, shaped by the seep of frogs, gravel and mud, and never the same from one moment to another, this stream may not be pretty, but as it travels through town it provides a secret freeway. Ignored by people, areas that are left alone like this are the calligraphy of the wild, tracing everything the living landscape needs.

Thin blue streaks on maps, we can find them, those nameless streams, as they sneak along contours to their wastegrounds and quietly merge with higher ranking and more charismatic siblings. This one, just outside the Co-op, is the water that drops down out of Olwen Wood and Long Wood, that slides in a ditch beside the road, slips under Station Terrace, flows through the town and makes its way across the university campus, a subtle, rough-edged lane of vole-friendly foliage. It has poured off the land and filtered from the springs fed by far off uplands and deep ground waters. Its birthplace was a sodden marsh or misty, reedy bog sung over by curlew and snipe. All this water is doing is seeking more water.

Climb the wall and descend into another version of time; this is seasonal time, not clock time. An unloved dimension. Stepping into it is like eavesdropping on a private conversation. This urban edge which nobody owns, where no one would normally listen in, these places to ignore or to tip out unwanted litter have their own secrets to discuss. Entering into this no-man’s-land helps get to know a place; just to hear each river’s voice, however foreign and fleeting, and to pause there, is to glimpse another world.

As the water moves, stare more closely, and the little stream uncovers itself. Weed straggles on the glistening silver wires of a supermarket trolley half submerged in mud, and tiny fish swim around the wheels as they mill the current. Close-to, the gravelly voice of the water gossips about the spawning of sea trout, the arrival of crayfish, the gradual encroachment of Himalayan Balsam, and the diminishing visits of swifts.

The Teifi’s waters spring from the watery wildness of the Teifi pools, deep marshy lakes which are situated more than 400 metres up in the Cambrian Mountains of mid Wales. The waters flow through upland pastures and raised mires and bogs, before meandering through meadow and pasture and being joined by tributaries such as this one at my feet.

A short scramble from the car park into a field beyond the road takes you to where this almost-pure, ottery little tributary jiggles into the more powerful flow of the main river. Children play here, their bodies shining with water and creatureliness, where at dusk the other creatures emerge. A little further downstream the banks meander through fields, and parts of the river are hidden behind a patchwork of purple loosestrife, Himalayan balsam, elm and alder.

The wet pathway draws you in on its own terms; wade in. Unpredictable and dynamic, the bed of this stream is deeply ridged and playful. It can spill over your welly tops in an instant. On a gravel beach are clawed signatures of otter; gravel and sand scraped into an odd little peak with some spraint deposited on the top. The water level is low. It has been a dry summer and a few weeks’ worth of otter comings and goings are apparent. There are scrapes and pad marks, and distinctive fresh-fish-and-jasmine aromas haunt the air.

Listen, so many different layers of sound and whirring voices, looping over one another with familiar jizz and energy. The cooing small talk of a pair of collared doves, woodpecker, warblers conversing over the layering of grasses and leaves.

Many townspeople would trail past oblivious that there could be an otter, or even a family of otters, curled up just metres away from them. Immersed in the glee of the summer waters, wild swimmers fling themselves out of their usual bodies and merge with some ancient, amniotic knowing. These ecstatic departures release us from the thinking human, and we can enter into the instinctive, deep play of animals.

Secluded in its jungle of alder, willow, iris, reeds, water dropwort, ferns, horsetail and sedge the river flows beneath midges, hoverflies; bees thread trails of sound, and beyond the flitting canopy of reflections, through the sensitive meniscus, is the viscous under-storey. Peer further, past the strange wobbling image of yourself, and from below the surface comes the bitter-sweet aroma of slime and mould from the mud as it composts. From inside the soup of this alien world, bizarre beings gaze. Dragonfly larvae and newts are suspended as if in molten amber; water snails and minnows feed on clouds of algae, trillions of bacteria swarm over everything; from beneath the surface, we are watched by a thousand eyes.

Move quietly past the riverbanks built up with rocks fixed firmly in baskets of strong wire. This is engineering designed for humans, not rivers. It is here to keep the river flowing along one fixed course, which being a river it would not choose, but the balance of requirements has to be met and compromises made. Where the river has not been altered, the banks tumble downward to the water there are reed beds, patches of marsh, sandbanks, fronds of weed, water meadow, gravel beaches, rocks and root-strewn cliffs. The water works its way around all, crammed with fishes and a whole array of invertebrates and water life. Catch the scent of meadow-sweet, invasive Himalayan balsam and, in the spaces between, purple loosestrife pushing its spectacular spires skyward. Patches of scrub and small trees create shade and shelter, shale lies in banks and, in the shallows, weed and watercress grow in harmony like a wild, watery herb garden.

Move quietly; wear clothes that don’t rustle; slip out at night.

See where the otter came out of the water, its sinuous pathway through the undergrowth cutting off a bend in the river. Has the dew in the grass been disturbed here, a tumble of mud in the bank been smoothed by webs or a water-darkened skin?

How well do you know your patch, this land in all its wrinkles and dips and phases? How is your intimacy with it, how would you deal with its loss?

An unfamiliar bird calls from the summit of an alder, the air limpid and the sky paling, feel the sonority moving through your ribcage. Bear witness. As the light fades listen; you may hear something which makes your hair prickle. A strange crunching sound coming from the direction of the water, and at your footsteps a subtle-soft ribbon of puffball-brown fur sliding into a whorl of bubbles.

Whenever we encounter wild creatures, it takes a few moments to adjust. Our senses register a strangeness for a split second. Then we might feel a prickle of recognition through our body. The sensation is redoubled when we can name this experience as salmon, vole, otter or eel. The alien movement of a wild animal is like nothing we have seen in pictures or screens, and perhaps at these moments of recognition we are at our most alert, our most animal. Encroaching more and more into the wildscapes of those tribes who were here long before we arrived, we can be forced into new contact. In the spaces outside time, they can remind us, by their appearance, that the divide between urban and rural, wild and civilised, between us and them, is not what we might think.

Miriam Darlington is the author of Otter Country. She teaches Literature and Creative Writing at Plymouth University.