Psychedelia and Other Colours

by Rob Chapman

Faber hardback, 656 pages. out now

Review by Emma Warren.

Influential eras are often reduced down to the point of total remove from the reality as it was lived, partly because reporters bring their assumptions to the telling and also because stories have an in-built tendency to become simplified with each repetition. A casual observer of history might assume that DJs at acid house clubs only played acid house music when in reality they also played industrial records by Nitzer Ebb and repurposed pop songs. If you wanted a nuanced understanding of psychedelia’s full impact you’d have to live in about five interlocking parallel universes – or you could just read all 592 pages of Rob Chapman’s epic evocation of acid, music and 1960s culture in America and England.

It’s not really a drug book, though. In Chapman’s hand lysergic acid diethylamide becomes a nano-camera, swooping from 1939 Bauhaus to an unspecified point in 1971, always tuning in to the lesser-swept corners of those worlds.

These lesser-swept corners throw up the dust motes of some very unusual suspects: there’s a great section on Victorian typefaces; another on the influence of Bauhaus light painter Moholy-Nagy; and a great aside about Ravi Shankar’s big brother popularising dance before his kid brother shortened ancient ragas for a reduced Western attention span. Characters usually shoe-horned into other cultural stories are ushered into the acid room, like Steve Reich or Don Buchla, who helped invent modular synthesis with his Buchla Box.

The book even makes The Beatles interesting again. Acid opened up what he calls their ‘inner Scouser’, and that interior turns out to be feminine. Their narrative, he says, ‘carries echoes of their girl group surrogacy. It’s a woman’s voice, a working class woman’s voice at that, gossipy, domestic, matter-of-fact when it wants to be but prone to wandering off the subject and making a short story long where circumstances permit.”

Chapman’s ability to see outside of the usual psychedelic perspective makes for dazzling reading, no more so than when he’s talking about the flip side of the acid-born garage bands of ‘60s America: girl groups. ‘The girl groups and garage groups reflect mirror images of pain and neurosis back at each other over a chasm littered with heartache and regret…. The girl groups and the garage bands were pop’s great unrequited double act.’

One of my favourite observations comes a page or two later: “There is one crucial difference in the gender dynamics: the girls have their group support system, their union, their choirs of call and response; the boys howl along through a barrage of fuzz.”

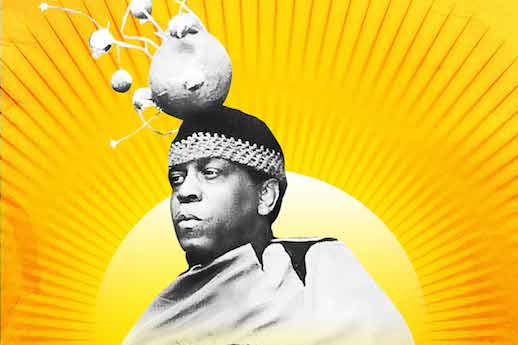

He’s pretty fearless, Chapman. As well as regularly pulling up psychedelic proponents for sexist lyrics, he goes full-pelt into the shifting sands of American racism, a place white writers generally fear to tread. The chapter titled I Am The Black Gold Of The Sun brings a mischievous verve to the subject – Bessie Smith, he relishes reminding us, is telling listeners to ‘kiss her black ass’. He makes plain his distain for the differences in the way that psych-tinged soul and R&B musicians were treated in comparison with the reverence shown to the blues musicians who were being rediscovered by the shack-load in the 1960s. An increasing number of voices, he says, consider the ‘authentic’ blues to be a twentieth century invention derived not from ‘the mists of mystic time or the post-diasporic consciousness of slavery, but in minstrelsy, the medicine shows and vaudeville’. It’s a dynamic that persists, with black music of the past safely lauded for authenticity and soul whilst contemporary artists are more easily seen as base, disposable or just plain ol’ commercial.

In this part of the book, psychedelia is less Grateful Dead and more Sun Ra’s interstellar invitations, Albert Ayler’s ‘Spirits Rejoice’ and Coltrane’s bridge building between LSD, jazz and sub-continental Indian spiritualism. If, like me, you like to step off the page to hear the music he’s talking about, then this book will take a while to read.

Chapman’s got an intimate knowledge of the music he’s writing about, allowing him to use a tiny Procol Harum cymbal tap or Soft Machine fade as a way of reflecting both the time it was made in, and LSD’s magnifying, fractal effects. It’s one of the most impressive things about the book, the sheer degree of note-by-note, riff-by-riff, beat-by-beat knowledge that underpins his narrative.

What else? There’s a fantastically readable chapter on the musical hall roots of British psychedelia, linking music hall tropes to The Small Face, The Kinks and David Bowie. It’s a bridging of the years, where character songs and tales of debt-filled drudgery exist simultaneously on rowdy 19th century stages and in Soho coffee spots a century later. There’s a nice detour into the ‘lion comique’, a music hall archetype made possible by the invention of cheap tailoring who is introduced as the forefather of sharply turned out, acid-tapped mods (and I’d suggest, their kid casual cousins in Sergio Tacchini a decade later).

It’s an incredibly detailed read, alternately funny and serious, and spiralling with lucid and colourful observations and insights.

‘The source of English arcadia,’ he says, towards the end of the book, ‘is the residual group memory of things, themes and places: fairgrounds and fairy tales, children’s comics and Saturday-morning pictures, Ovaltine commercials and Radio London, jingles, penny liquorish sticks, Bazooka Joe bubblegum cards and the corner shops that sold them.’

Rob Chapman will be talking psychedelia on the Caught by the River stage at The Good Life Experience in September. Info here.