Words and pictures: Cally Callomon

Words and pictures: Cally Callomon

My booted foot hits the soaking grass and the water droplets perch on my toe cap like transparent pearls. They do not soak the leather – discolouring it as they usually seep into its tiny pores – they are apart, solitary beads of winter rain.

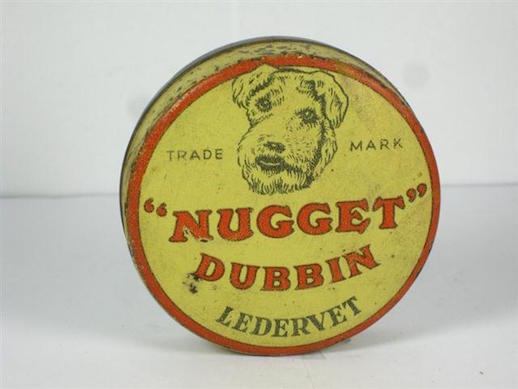

Now is the time of year where the wardrobe changes, where pullovers emerge from summer slumber, where the boots come out and the dubbin goes on.

Like all good things; dubbin comes in tins as a concoction of wax, oil and tallow, rendering this unsuitable for most vegetarians other than I. When challenged as to why I don’t eat meat I’m often asked why I wear leather boots. “I don’t eat my boots” is the only answer I can give, and my boots, built especially for me by William Lennons in Derbyshire, like the cows that created them, need feeding. We feed cows to cows: beef fat (tallow) to fat beefy boots.

I took a pair of worn out cracked 1930s Buckinghams up to Lennons and they used them as a model to build me new boots, perfect in every recreated detail, they even rescued and applied the cotton heel pull-on tab from the originals, like building a new Bugatti around an original radiator, the new boots were begat of the old ones.

My mother made me polish my shoes for school. Reluctantly I’d smear the pitch-black Kiwi onto my Tufs – a shoe made with a cheap dimpled leather composite that didn’t reward me with a shine, just an ungrateful mottled black dull complexion. I never saw the point and dragged them on the pavement on the way home hoping they’d wear out. No-one bought me Wayfinders with the compass in the heel and animal tracks on the sole, I come from a broken home.

To Dubbin a boot is not to covet it like a decent shoe polish. It’s the narcotic of shoecare; you need ‘works’ to gently heat the stuff, you need a separate brush with which to apply it. There is no smug final brush-off so that the leather gleams back at you, no, there’s just the dense heady oily matt finish of a boot prepared to repel moisture, sacrificing the vanity of the shine for the comfort of dry feet. All with a dense vapour like meths and petrol and tar.

Sometime in the olden days, man realised that this valuable oily spew, when applied to leather, kept the best side dry, and so dubbin was invented, the word derived from the gerund describing the action of the dub: applying the stuff to leather, just as sound is dubbed onto film, so we dub leather to make it work better.

Dubbined boots stop squeaking, but the very gum that saves any decent boot also heralds their demise, as the oil destroys the stitching that binds the uppers to the lowers: feet get wet one way or the other. Yet today I welcome the wet season; I can march through puddles, I can marvel at the coffee-rich mud spatters that sit on top of the boot, the rich fecal detritus of road, track and field, my feetal attire pressed into another year’s service, one that may well outlive me and become models for new boots to be made, new boots to then be coated in fresh dubbin.