The Kindred Of The Kibbo Kift: Intellectual Barbarians by Annebella Pollen

(Donlon Books, £35)

Review by Ben Myers

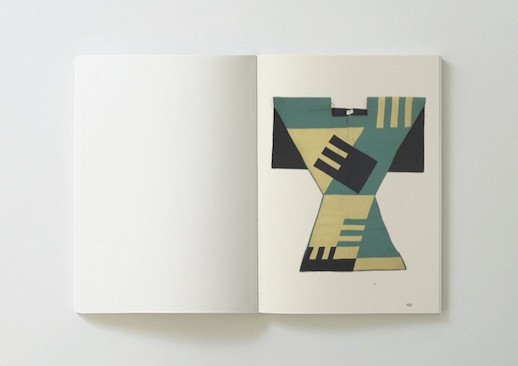

As with any youth subculture or movement worth its salt, it’s the clothes you notice first: a visually arresting array of ritualistic robes and austere smocks that suggest an earthen practicality. Here is a symbolically-loaded sartorial aesthetic with a clear message of purity in both presentation and purpose, one that recalls a wealth of disparate styles through the ages – Masonic robes, the sinister hoods and cowls of another KKK, the pastel-toned regimentation of Baden-Powell’s nascent scouting movement, the burgeoning Hitler Youth, the folk horror symbolism of The Wicker Man et al, plus a nod towards all manner of secret Victorian exponents of the dark magickal arts.

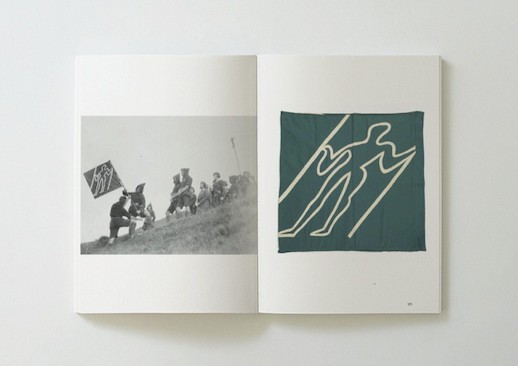

Then there are the activities that these lean, clear-skinned youths are photographed doing in their uniforms: from practising woodcraft skills and striding joyously through the countryside and striking ersatz poses on ancient landmarks of Wiltshire and Dorset, to conducting outdoor ceremonies that evoke long-buried memories of Britain’s pagan past.

This is The Kindred of the Kibbo Kift, a movement formed by charismatic founder John Hargreave in the shadow of WW1, with the express intention of developing a group of individuals of any age who were healthy, skilled, creative, progressively-minded and in-tune with the environment around them. Hargreave wanted nothing less than a master-race from which a better society could develop.

If this vision sounds sinister, then it needs to judged in context: Hargreave, a keen designer, accomplished writer and early member of the Scouting movement, had seen some of the strongest and most intelligent people of his generation blown to smithereens in foreign fields. From the ashes of war he hoped to raise a new consciousness and shape civilisation in such a way that the psychic damage of the recent past could be repaired and the tragedy never to be repeated. His and his co-founders’ aims were worldwide unity, harmony and understanding. To do this he proposed a return to spiritual values in an increasingly materialistic world, through the pursuit of simple activities such as camping, hiking, fraternity, fresh air and an appreciation of the sublime power of the English countryside.

The Kibbo Kift’s story is lavishly represented here via sourced photographs that depict not only the groups meetings, rituals and communal exercises such as rambling, tree-climbing or parading, but also in their ephemera – a strange and wonderful collection of hand-carved items, flags, patches and symbols whose bold imagery and clean designs recall two art movements of a similar era, Futurism and Vorticism. The impressively researched accompanying text by Annebella Pollen, an academic specialising in the History Of Art & Design, elevates this study from being far more than an art book and places The Kibbo Kift in a broader social context.

To contemporary eyes, Hargreave and his keen acolytes present something of a dichotomy: on the one hand they appear mystical, secretive and – initially at least – as malevolent as anything that falls into the folk horror category (and their interest in eugenics sinister given what we now know happened in WWII), yet on the other they had an appreciation for what author Pollen describes as a profound and “deep-rooted interest in comparative religion, their pantheistic belief in the spiritual immanence of all thing – not least in the ancient rural English landscape – and a modern world infused with the myths and mysteries of an earlier, more primitive age.” Their membership was comprised of “more than usually conscious individuals comprised of a range of seekers of spiritual as well a social solutions to contemporary problems”.

They were no crack-pot outsiders, then. Eugenics theories deemed suspect by today’s standards were widely discussed during the confused, innocence-shattered years that followed WWI, and Hargreave believed that the Kibbo Kift and their ideas that called for change could work in tangent rather than opposition to a number of already existing groups – from Montessori educational organisations and the English Folk Dance Society through to political parties including the Labour Party, Socialist Party and the Fabian Society.

The Kibbo Kift were gentle radicals – pacifist and inclusive, and merely the latest in a long line of organisations combining the physical with the philosophical. One example from the early 1900s was the Nature Boys, a collective of young proto-hippies, many of them German immigrants, who lived in and around the canyons of LA and practiced Lebensreform – a “life-reform” lifestyle of nature worship, raw foods, nudity and crafts. (Side-note: one of their members, Eden Ahbez, later penned a hit single called ‘Nature Boy’ for Nat King Cole, which brought the group to wider attention).

Though their projected image was one of Nietzschean strength and purity, The Kindred Of The Kibbo Kift were more National Trust than National Socialist; closer to Carry On Camping than Mein Kampf. They were thoroughly, brilliantly English. They were John Betjeman and British Sea Power, Ray Mears and the Romantics. Annebella Pollen and publisher Donlon Books have curated a real treasure trove from the Kibbo Kift’s widespread artefacts, adding one more chapter to an ongoing archive of eccentric and inspiring English stories.