Review by Roy Wilkinson

Avian archetypes have regularly featured in folk songs – in songs such as ‘There Were Three Ravens Sat On A Tree’, or ‘I Was A Blackbird’, or ‘Grey Goose’, the latter as sung by Leadbelly and reprised by Nirvana. With this 1978 album, now reissued in beautiful style by Earth Records, British folk-guitar master Bert Jansch took the title from a more obscure creature – the elegant black-and-white, bent-billed wading bird. In Britain the avocet had been shotgun-ed to extinction by the mid 19th century. In 1947 it returned to the East Anglian coast, its re-emergence inadvertently aided by the miles of shoreline that had been flooded to thwart a possible Nazi invasion. The avocet’s precarious foothold combined with the bird’s distinctive profile to make it a striking choice for the RSPB logo. Today there are over 400 breeding pairs of avocet in Britain, but in 1978 there were less than 100. The bird’s physical presence and its back-from-the-dead backstory made it an alluring, tantalising thing.

The avocet’s behaviour doesn’t always square with its photogenic finery. It’s sometimes known to birdwatchers as ‘Exocet’, after the French anti-shipping missile that brought such death and destruction to the Royal Navy during the Falklands War. During the breeding season, avocets launch themselves with neurotic urgency at other birds. These attacks are triggered if interlopers come close to the barely-there nests the avocets have fashioned at the water’s edge. This writer once watched avocets exercising their goofy guardianship at the Norfolk Wildlife Trust reserve at Cley Marshes on the north Norfolk coast. Avocets repeatedly staged buffoonish aggression toward ducks and moorhens, birds that carried no threat to the avocets’ young. While flapping away at these benign intruders they left their offspring exposed to real peril. The cute, fluffy chicks – complete with miniature versions of the adults’ decurved bills – were at the mercy of herring gulls overhead, their basilisk eyes laser-ing in on the abandoned young. Avocet nests are also prone to flooding. You wonder how the next generation ever emerges from this creature’s baffling parenting strategies.

The word avocet comes from the French avocette or the Italian avosetta. It’s a name as elegant as the creature it applies to. But the bird’s blowhard bluster is better reflected in its various British colloquial names: barker, crooked bill, yarwhelp, yelper. For the six instrumentals on Avocet, Jansch’s guitar and piano are accompanied by Martin Jenkins on violin, flute and mandocello and Danny Thompson on double bass. These men are, of course, supreme and skilled players, but their work on Avocet is often closer to the rustic what-you-see-is-what-you-get of ‘yelper’ than the Italianate daintiness of ‘avosetta’. After all, Martin Jenkins had previously played in bands named with the folk-rock thump of Dando Shaft and Hedgehog Pie – as pointed out in the album’s informative sleevenotes, written by Colin Harper, author of the Jansch biography Dazzling Stranger. The 18-minute title track of Avocet takes as its starting point the ancient English folk song ‘The Cuckoo’. There’s none of the literal link between song title and sound that’s there in, say, Fleetwood Mac’s ‘Albatross’ – a recording where cymbals mimic the susurration of the sea and guitar lines suggest seabirds calling. Avocet’s title track is a twisting, immersive, abstract journey, actually more woody than salty. Thompson’s bass twangs like taut leather and, in the piece’s final third, Jenkins’ flute has something of Jethro Tull.

The five tracks that follow ‘Avocet’ are named after other birds of water and the shore: Lapwing, Bittern, Kingfisher, Osprey and Kittiwake. When the album was released in Denmark, ‘Kittiwake’ was called ‘Goldfinch’ – underlining the somewhat random marriage of music and titles. The musical content is evocative of interiors visited after glorious hours in the exteriors, rather than the outdoors itself. It’s as if the wind has blown cold but now it’s time to sit by the fire and reflect. Imagine. It’s 1978 on the celebrated birdwatching shingle of Cley. Storms are raging. The telephone is down at the legendary ornithological epicentre that was Nancy’s Cafe – blacking out news of sightings of a rare red-breasted goose just off the esteemed East Bank. But, fear not, a juvenile dotterel has been spotted and food and wine now await in the pub. The folk-blues étude of ‘Bittern’ would be a wondrous soundtrack in such circumstances. As would the pretty guitar curlicues of ‘Kittiwake’ – even if they really are more akin to a goldfinch. The album as a whole is a sonorous delight, the lack of words-as-waymarks or drum-based punctuation making the 30-odd minutes seem vast – a lovely labyrinth of strings and occasional flute. It seems you could listen forever and often find something new.

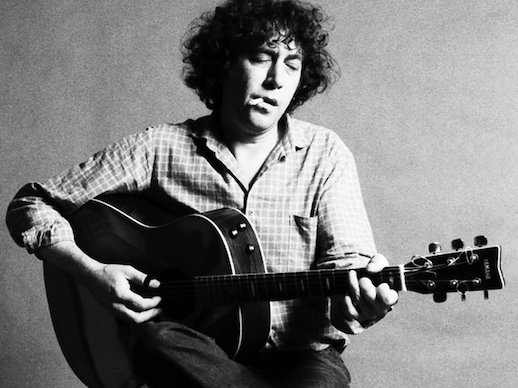

The reissue packaging is worthy of the audio content. On the album’s original release the cover image was a shoreline scene featuring the six birds of the titles – a skilfully-wrought but stylistically-anonymous image. For this reissue, the vinyl version comes with illustrator Hannah Alice’s six attractive, stylised illustrations of the title birds. The front cover features a cut-out frame, into which you can set your own favoured cover star and then swap them at will. Avocet/yarwhelp. Bittern/bog-blutter. Lapwing/peewit. The choice is yours, and it all forms a fitting forum for a lovely work from the much-missed Jansch. Here was one of the greats of the guitar, but someone whose innate tastefulness and tendency to understatement – combined with the absence of a track with the universality of ‘Albatross’ – meant he was sometimes as hidden from sight as the bittern in the reeds. The album is also reissued as CD, where the bird illustrations and sleeve text are contained within a tall-format book.

All formats of Avocet are available to buy direct from Earth.