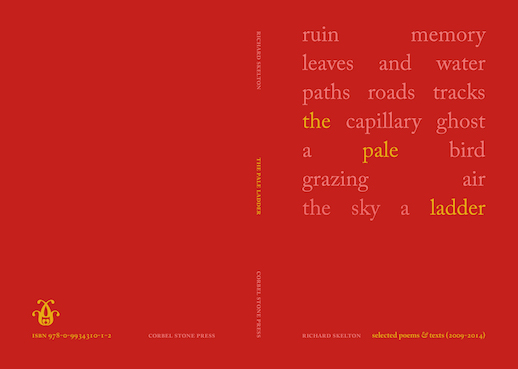

The Pale Ladder: selected poems & texts by Richard Skelton

The Pale Ladder: selected poems & texts by Richard Skelton

(Corbel Stone Press, 262 pages, softcover. Out now.)

Words: Alice Tarbuck

Richard Skelton’s The Pale Ladder is quite extraordinary. It is as strikingly beautiful a book as one would expect from Corbel Stone Press, the micro-press that he and artist Autumn Richardson founded together . Corbel Stone Press takes it aesthetic cues from fellow small-print presses such as Peter Foolen Editions and Tom and Laurie Clark’s Moschatel Press. Colour, paper-weight, font and sizing are all given scrupulous attention. It is also a fascinating testament to Skelton’s evolution as a poet and writer. The Pale Ladder anthologises Skelton’s writings from 2009-2014, and over this half decade the focus, form and flow of his work alters considerably.

The book opens with a selection from his 2009 Landings, Valley of the Small River, in which Skelton begins to frame some of the significant questions that run like strands throughout The Pale Ladder. In Inventory, he asks: ‘How to begin writing this down? Shall it be a simple inventory? A list of parts. Names. Dates.’ This vexed question of representation is familiar to all nature writers. How might anybody writing in the anthropocene frame human encounters with natural spaces? There are always political, ethical and ecological pressures at work. Skelton seeks to move beyond field notes and first-person narrative, to find an ethical way of recording the history, geography, and allure of the landscapes he closely inhabits.

His 2009 selections are certainly ‘Landings’ – they are fresh with the sense of arrival and promise. Picking his way amongst nature writing traditions, these early works are often close critical encounters with the Romantic tradition. ‘Scar Tissue’, which documents the examination of a photograph, closes with an image of ‘collapse, decay, and gradual surrender’ – an emotive evocation of a golden age that only ever half-existed. Works like ‘Something More than Proximity’, which uses found text to create poetry in the tradition of Thomas A. Clark’s early works, evoke the realities of landscape (in this case, hills and their heights) without sentimentality. Skelton is often at his best in works that gesture toward the natural world, rather than describing it directly. It is here that he can best demonstrate his formally innovative tendencies.

Some pieces of text, such as ‘Firmament’, engage with post-industrial land use. Throughout The Pale Ladder, technology, industry and man-made objects play an uneasy role – sometimes indispensable, never exactly welcome. In, ‘Firmament’ the sky is suddenly filled with something – ‘Hundreds, it seemed, high, high up in the firmament. They seemed to multiply before our eyes. The sky, sick with hem. Metal, burning’. The reader is left unsure as to what the walkers have encountered. It might be aeroplanes – it might simply be a vast flock of starlings, their movements strange and mechanistic. The interplay between the natural world and man-made objects offers a fascinating strain throughout the collection. There is more than a hint of Richard Jeffries’ desire that ‘the mist eats away the sharpness of […] iron angles’, naturalising machinery into the landscape, albeit partially.

The ‘unnatural’ is joined by the ‘supernatural’ in parts of Skelton’s collection. Whilst he is not deeply embedded in the mythology of wild places, he also shies away from the naturalist’s role. In ‘The River Beneath’ he describes a ‘dark/cascade. A black/and ceaseless torrent. […] a line/that you can/ never cross’. This underground river conjures images of the Styx, offers a sudden strangeness in the landscape. Indeed, in inclusions from 2010 collection Wolf Notes, Skelton explores the place of wolves in British consciousness, culture, and terrain: ‘Ulpha Fell, a reproach;/ the hill silenced by wolves’. Wolves haunt these poems, as absences, echoes, moments of memory. In ‘Formless’, there walks:

a form less

clothes than air

tirelessly stitching-unstitching

hill side, moor and fell

It may be benign – a walker, or growing dusk – but there is space left for a more uncanny explanation.

As the collection reaches 2012-2014 there is an increase in Skelton’s use of innovative and unusual form. ‘An Immense Morass Shut In Between the Sea On One Side and Mountains On the Other’ is a poem that uses a long title to contextualise a minimalist poem. The poem itself is fragmented: ‘a sector/of/vastness’, revealed to the reader only briefly and partially. Skelton’s innovation places him amongst those in Harriet Tarlo’s 2011 collection The Ground Aslant, writers who she grouped as being ‘Radical Landscape poets’ – Frances Presley, Peter Riley, Tarlo herself. Skelton is arguably at his best when, like those poets, he is experimenting with form. In ‘Moor Glisk’ we encounter language as wild as unknown landscape:

þryne holegn elm alor wice

These are linguistic evolutions – historic names for trees or features in landscape. Their beauty is in their strangeness – the unusual feel of them over the tongue. Skelton’s approach throughout the selected works is one that speaks to collecting, observing, recording – and whilst his poetry is evocative and beautiful, it does not shy away from difficulty. Indeed, Skelton is invested in the phenomenology of landscape, what happens when the viewer can ‘dismantle transform become’ the land that surrounds them. The freedom that this approach grants is one of selection – it allows the view to rest on the ‘threads of a warp/ a shred/ a fragment’ rather than being governed by a desire for a complete landscape or vista. Certainly, toward the end of the collection, Skelton has shed any remaining Romantic vocabulary in exchange for formal innovation and language that balances evocation and exploration. This is an extraordinarily rich collection, and one that reveals Skelton to be a major voice in landscape writing.