A new series of posts following Tom Bolton – author of ‘London’s Lost Rivers’ and ‘London’s Lost Neighbourhoods’ – as he travels the coastline of the British Isles.

At the late August Bank Holiday arrived, Jo and I headed back out to the Essex coast for the next instalment of our summer mission to walk its tangle of flats, estuaries and saltings. At home in South London everything was on hold as we waited for the Mastic Man, a demanding and mysterious figure who would perform specialist tasks in our bathroom. His arrival might be unannounced: we were told he sometimes liked to surprise. In the meantime, we had to keep things “bone-dry for the Mastic Man”, and the damp Essex expanses offered respite.

Marking the shifting edge of eastern England was a convoluted process. This time we planned a circumnavigation of Mersea Island, the third largest in Essex after Canvey and Foulness and home to the nation’s prime oyster beds. We returned to Colchester, a fortified hilltop town commanding the marshy coast. Outside the station a billboard that proclaimed “The Truth. Legal Name Fraud.” These posters had appeared that summer all over England, a material world spillover of a bizarre internet conspiracy theory about identity. Attempts to identify those behind the campaign had failed, and the trail ended with a Canadian woman known as ‘Kate of Gaia’. The appearance of these posters had been, in retrospect, an omen of a summer in which fringe politics had veered suddenly into the mainstream.

A heavily timbered, 15th century coaching inn did a good deal on bed and breakfast. It seemed deserted, but the receptionist told us in a matter-of-fact tone that she was bothered by three ghosts: a basement monk, a boy in the breakfast room and Alice, the obligatory victim of thwarted love. A troop of ghost hunters had hired the place the night before, we were informed. One man had left early, upset by something he had seen. “You’d have thought he’d be happy”, the receptionist suggested, “That’s what he came for”.

The bus to Mersea Island took a suburban route, tracing a slow loop around the suggestively named Lethe Grove where the south Colchester estates were snared in an enchanted oblivion. The enormous pub at the centre of Abberton was comprehensively boarded up. Out of sight of the village centre lay the expanse of Abberton Reservoir, used in 1943 by the RAF to practise bombing runs for Operation Chastise, the Dambusters’ raid. ‘Danger! Troops Training’ signs indicated the continued presence of the military, housed at Colchester Garrison and dispatched to train on woodland and marsh between the town and the sea. The MoD, under pressure to dispose of assets, had just announced the sale of Middlewick Ranges on the edge of town for housing.

Mersea Island had a single access point, The Strood, a bridge over the tidal channel that separated it from the mainland. The road became submerged at high tide, when cars were obliged to wait it out on Mersea for the ebb tide. Successfully making the crossing on a single-decker, we paced out along a sea wall which formed the most permanent feature of the shifting north shore. Signs warned of diversions and collapse, but the path was clearly visible retreating into the distance, the highest point in a flat, watery vista. The tall marsh grass had scorched to a dry yellow during the hottest East Anglian summer for a decade. We crossed a farm where the turf had been grazed short by sheep, cropped to the line of the causeway. The path seemed to pass along an illusory South Downs ridge, the valley below flooded during a sudden coastal influx.

We turned the eastern corner of the island, opening up views across the Colne estuary to the small harbour at Brightlingsea. At Mersea Stone Point, the easternmost point of the island, the reported remains of a Tudor fort had vanished under the sea and the Stone could not be detected. A scout camp on Essex County Council land pitched heavy green canvas tents, the same model we both remembered from the 1980s. Touch the sides in wet weather and the seal would break, letting in the rain.

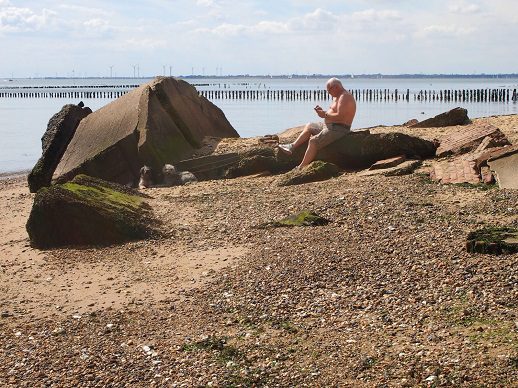

Uninhabited East Mersea began to give way to well-visited beaches. At Cudmore Grove Country Park, where elephant and hippopotamus bones had been found, the cliffs were low. Coastal defences, built to fight an invasion that never came, had fallen as the friable, ochre soil gave way. The beach below was strewn with tumbled concrete lozenges, pill boxes spilled towards the North Sea.

The coast here was retreating fast, trees falling in slow motion as the subsoil washed steadily away. To keep Mersea intact, polders had been laid offshore. These low fence lines marking out fields in the sea were a Dutch invention to trap sediment and keep the sea back. The Dutch had been reclaiming Essex for centuries, since 1622 when Cornelius Vermuyden arrived to build a sea wall around Canvey. These polders seemed to be struggling, but the dogs and bank holiday families were taking no notice. The isolation and desertion of the Essex marshlands was evaporating, and the narrow road to Coopers Beach Holiday Park soon became congested with brand new white Land Rovers and the odd Porsche. For the first time on the Essex coast, we found ourselves following the money.

Our lunch stop was a small pub with a car park full of high end transport, drawn by the seafood. Mersea’s not-so-secret weapons were the native oysters fattened in its channels since Roman times. Mehalah’s, a foodie stop in the middle of nowhere, was named after Mersea’s one-and-only novel. It was written by the polymath parson at nearby East Mersea church, Sabine Baring-Gould, composer of hymns such as ‘Onward Christian Soldiers’, collector of West Country folk songs and author of all sixteen volumes of ‘The Lives of the Saints’. He had spent 10 years as Rector of East Mersea in the 1870s, exiled for his troublesome criticisms of the Church. Mehalah: A Story of the Salt Marshes was a sensation, a dark, elemental, family tragedy compared favourably by contemporaries with Wuthering Heights.

Back on the south shore, the coast path was fenced and diverted. Climbing over we discovered a stretch of concrete-topped sea wall strewn like dominos by the crumbled cliffs. The Mersea coast seemed to be melting away before our eyes, but the twin cement boxes of Bradwell Nuclear Power Station appeared on the horizon, the only visible structures remaining intact.

Oyster shells had collected in vast quantities on the beach. Found on Thames beaches only as a reminder of 19th century diets, the oyster shells of Mersea were displacing the shingle, forming a protective bulwark around a fragile island. The Romans, arriving in Essex to deal with the Iceni, stayed to fortify Colchester and had laid oyster beds at Mersea, where they liked to come on holiday. Oyster farming rights on Mersea dated back to Edward the Confessor, and shellfish were the fabric of the island.

The beach huts of West Mersea inched into view, lined up along a mile of sand in uncompromising pastels. The heat was suddenly intense, searing the bathers but pursued by a weather system stacking tall, dark clouds over the Blackwater Estuary. As we hit town, the sun disappeared and a line seemed to be drawn under the long, dry summer. The narrow pavements of West Mersea were full and its pubs and oyster restaurants booked up, the Range Rovers parked up outside. The east shore was a tidal mudflat, boats lodged in low tide creeks homemade plank walks linking them precariously to dry land. The channel beyond was known as The Gut.

The town’s medieval lanes and high hedges had been festooned with union jacks. They turned out to be left over from an island-wide party the previous night, for West Mersea yachtswoman Saskia Clark who had just returned from the Rio Olympics with a gold medal. The connection between Mersea and wider global events came as a surprise. Although the island seemed a long way from mainland concerns, it was clearly feeling the pressure. A poster protested against Colchester Borough Council’s plans to build houses in empty East Mersea, and prophesied “The Mersea way of life, gone for ever.”

Stepping back from the edge, we made the transition to the material world via The Strood and Lethe Grove. The journey from mud and oysters to familiar, solid surfaces allowed us to acclimatise, and by the time we reached London, Mersea Island seemed an illusion, perhaps caused by heat on water.

*

Read the previous instalment of Tom’s column here.