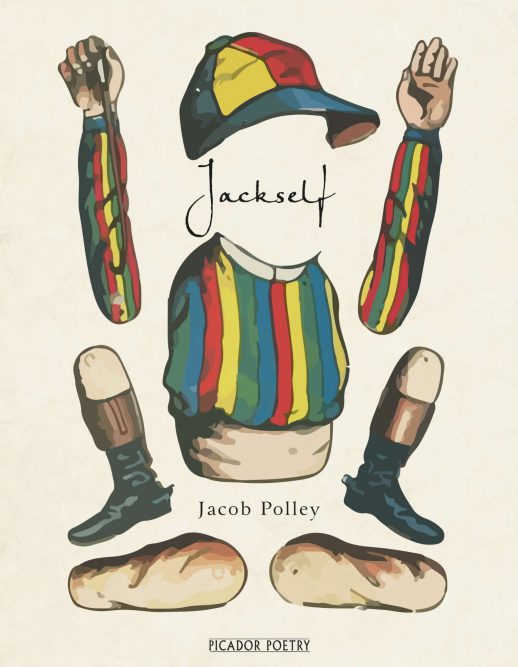

Jackself by Jacob Polley (Picador, paperback, 80 pages. Out now and available here.)

Review by Martha Sprackland

who’s at the door of the door of the door

who else but Jackself, the folktale hero of this ‘fictionalised autobiography’. In the fourth collection from Geoffrey Faber Memorial Award-winning Jacob Polley, myth and nightmare are glimpsed through the loose-held narrative of a childhood in the wild old spaces of imagined Lamanby, somewhere on the Cumbrian border, where the poet is from. This alternate universe is announced at the end of the spectacular opening poem ‘The House that Jack Built’, a rattling prologue in sped-up footage, like a zoom-through of the distant and recent past. ‘[T]he first trees were felled’, and centuries later ‘ripped up by a legion’s engineers’; in another age they were ‘half-buried, grown-over, still hot / were stumbled upon / by navigators’, are lock-gates, ship-timbers, monuments, firewood, house. This is pummelling, overwhelming – the freight train of history flashing by, evoking the million layers of time that lie over a place – until the last line comes home on that final word, like the lights-down of a Shakespearean preamble, like the last boulder after an avalanche coming to rest in a hollow at the foot of the mountain:

weren’t felled but walled in, roofed over, giving span to a farmhouse, hanging a hall from their outstretch, bracing floor after floor on their inosculating joists, which sang to a barefoot tread and were called home of shadows heart of the wind Lamanby

Jackself is a concept album, a fantasia on the rural places of the north, a charm-song closer to nightmare than lullaby. This has come under Polley’s remit before; in his last book, The Havocs, also shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize, the modern cautionary tale ‘Langley Lane’ contained – in its title, in its content and in its song-form – echoes of Long Lankin, bogeyman of the wild and dangerous places. In this poem the marsh and the moss were exchanged for the suburban lonning and the concealed knife, but no less sinister a character is it who jags out of the darkness and takes your blood. Here in Jackself we find, as the book’s blurb warns we will, other characters of lore, ‘the many ‘Jacks’ of English legend … Jack Frost and Jack-O’Lantern, Cheapjacks and Jackdaws’, though this is somewhat misleading; the dramatis personae in fact a skeleton crew of Jackself, his friend Jeremy Wren, and the just-seen parents, Mudder and Mugginshere. Where these ‘many Jacks’ play a role it’s one of costume, of disguise – these multiple Jacks shift and coalesce to form the one Jack.

Ted Hughes and his Crow are presiding spirits, perhaps, over these wintry landscapes, but slant: the force of the natural world here less towering and shamanic, more elusively threatening by being on the point of disintegration. Polley’s natural world is characterised by entropy, by potential collapse: the ‘water- / damaged sky’, ‘the rain’s turning to sleet / snakes eat their own skins’, the ‘fly-tipped / black plastic sacks’ strewn among the bracken. Brick is fungal, wood is rot, metal is rust, leaves are slime.

If things at ground-level are corroded, raddled with decay, this might explain why Jackself yearns upwards. He leaps to catch the moon, his fingers ‘scrabbling a crater-rim’, making for that high realm where his dead friend, Jeremy Wren, resides, in ‘the dark air / and up towards the unutterable thing’. The Havocs is recalled here – where last the adult climbed ‘the steep empty staircase’ to the attic room he used to sleep in as a child (‘Apples and Pears’), here Jackself makes frequent visits to ‘the lovely lofts of Lamanby’, a high-up world wreathed in the dusty, shimmering silver strands of webs, ‘the mercury lyres / of the spider’s wires’. This is a motif sewn through this collection, echoed in the nylon fishing-lines in ‘Nightlines’, and the ‘silver thread unspooling from his chin’ as the adolescent Jackself and Jeremy Wren get drunk on white cider in the hedgerows. The home-notes of these poems – the wind, the webs, the worms, the apples and the geese, the undersides of stones, the fire and snow – sound again and again like church bells through fog, to keep us always aware that the child, the adolescent and the man are all one life, lived here in Lamanby with its familiar objects.

There’s a double-page spread, Christopher Logue-style, early on in the book, when Jackself is a child:

D O N ’ T W A K E H I M

huge in bold black (a little lost to the gutter, unfortunately, at least in my copy). So when later in the book Jeremy Wren shakes the older Jackself from his dream – ‘WAKE UP / Wren yells, and Jackself starts’ – we come out of the sleep of childhood with him. This particular poem seethes with buried violence; Wren has built himself a replacement father, a nine-foot figure radiating cold,

so I can give him a smile stonier than a lip smile poke myself in the eyes on his hand sticks run clean through him and leave a me-hole hide a penny in his body so when he’s gone, I get him back (‘Snow Dad’)

This is the beginning of the loss of innocence, the awakening of the adult, the violence of Jeremy Wren’s misery before he ‘throws a dressing-gown cord / over the rafter in his bedroom’. Polley is adept at writing this darkness, the nightmarish howl of wretchedness:

Jeremy Wren, whole of heart, tell us what pains you my hole is bigger inside than out and the heart of my pain is a black bull’s heart and the tongue of my pain a black bull’s tongue that every day licks off the cream of the light (‘It’)

Later, Wren, dead and buried, whispers again his invocation as he

drifts with the chimney smoke and settles like goose-down on the water wake up, Wren says (‘The Misery’)

and brings Jackself to his own grief, his misery, the ‘gristly’, cold monster he defeats in order to cry, to come back to himself. It’s not a complete recovery, it can never be a complete healing, a wholeness – the world was damaged, and won’t be the same again, but this second awakening is definitely redemptive, and

by the time he’s under the outside light of Lamanby, Jackself’s shaken his heart clean and full of fresh night air (‘Jackself’s Boast’)

There’s so much more to say about this book, about Polley’s transfigurative skills (see ‘Peewit’, see ‘Applejack’), his perfect snowglobe-world metaphors, the meeting of the rural and the urban, the use of form. It’s a completely original collection (though with shades of Berryman’s Dream Songs, sure, in the relationship between Jackself and Jeremy Wren), a frightening, exhilarating, affecting book which rewards – demands – repeat visits. Reading Jackself is a rich, consuming experience, in which the life of one character is told through the dark, often desolate land of winter and nighttime, where the passing of time is keenly felt, where history is at hand in the rafters and floorboards of an old house, in the ‘coelecanth and dead zone’ fathoms down. Lamanby, and Jackself, are short chapters in the life of this world.

Towards the end of the collection we often find Jackself standing on the edge of a body of water, watching the night fall over the estuary or the tide turning over the rock pools. It feels just right that the adult Jackself ‘heels off / his trainers, balls up his socks, / rolls up his jeans and wades / in among the stars’, recalling the young boy years earlier, the sensitive one, the ‘soft-lad’, who, night-fishing with Jeremy Wren, does his own waking:

rolls up his jeans, takes one end of the nylon line looped to a tent peg and wades into the chuckling shallows slippery-stoned ice-cool fishpath where no one has stood for a thousand years when Wren’s not looking Jackself stamps his foot and all the carp and sticklebacks, the perch and pike and bream are shaken out of their gullible, muddy-minded dream. (‘Nightlines’)

*

Jackself is shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize for Poetry, the winner of which will be announced this evening at the awards ceremony in London.

Martha joins us at Machpelah Mill, Hebden Bridge, this Saturday, for an afternoon of poetry and prose. More info/tickets here.