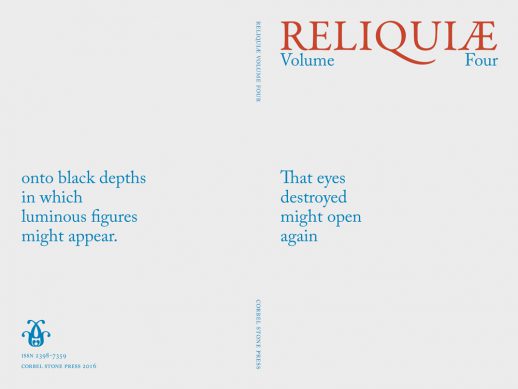

RELIQUIÆ Volume 4, edited by Autumn Richardson and Richard Skelton

(Corbel Stone Press, softcover, 180 pages. Out now and available here)

Review by Katharine Norbury

I was puzzled as I turned over the brown paper package. The word “FRAGILE” was written in large cursive script across the front. Inside, wrapped in tissue paper, was an exquisite soft-back, snow white book.

This is the 4th volume of the annually published Reliquiæ, a journal of poetry, short fiction, non-fiction, translation and visual art, compiled by Autumn Richardson and Richard Skelton. A note on one of the pre-leaves states that “each issue collects together both old and new work from a diverse range of writers and artists with common interests spanning landscape, ecology, folklore, esoteric philosophy and animism.” The contributors themselves are not described. Their work speaks for them. Although certain pieces are given a context e.g. “Excerpts from a nine day walk across Scotland”, or “A story from Povungnituk, Quebec, translated by Zebedee Nungak and Eugene Arima”, there are no biographies, no indication as to whether the contributors are living or dead, young or old. Some of the names were familiar; others were new to me. For the most part I was intrigued and, indeed, delighted by this, although I confess that I was disappointed to realise that of the thirty-three contributors, only six of the names were obviously female.

“Reliquiæ” means, essentially, things left behind. It isn’t a synonym for “reliquary” – a receptacle where sacred fragments are preserved – but rather refers to the remains themselves: the grey chip of a hermit’s elbow, a twisted braid of golden hair, seeds preserved for over 30,000 years in a forgotten Arctic hibernation burrow.

There is a thematic progression throughout the journal. It was published in the dead of winter, and ice is its first subject. But there is an implicit feeling that what we are seeing is already the remains of ice, a description of it, and that real ice was something from long ago, fragile, continually in flux and perhaps, by the time this book is read, lost. Wendy Mulford begins her Orkney poem Planticrue: A Lament with the words: “here, after the ice” and it is these five words that capture the essence of Reliquiæ 4. A concrete poem, Ice Voices by Robert Macfarlane, is a sliver of words packed between tight margins that mimics in form a 10cm by 150cm cylinder of East Greenland’s ice. “Ice cores are cylinders of ice drilled out of an ice sheet or glacier, and studied for the archive they contain,” Macfarlane tells us. “The oldest continuous ice core records from Greenland extend 123,000 years back in time.” Pressed between the ten centimetre margins are the voices of those who have inhabited the place from which this particular ice core was taken. Macfarlane’s own, wondrously, is amongst them. I was reminded of Alice Oswald’s multi-voiced poem Dart, but unlike Oswald’s scripted work, Macfarlane offers no clue as to whom these disembodied voices belong. Instead, a list of names invites the reader to disentangle and attribute the transcript for themselves; to become a part of the process of sorting, catalogue, archive and conservation.

…there’s going to be a lot of billionaires made by that new land! We have created an ocean Where there was once an ice sheet

The politics is unavoidable – how many of us have stopped to think of the vast potential for financial gain that the brand new, soon to be revealed landscape of Greenland embodies? And yet this is not an embittered polemic. Rather, Macfarlane sculpts the catastrophe of Greenland’s ice melt into a splinter of rugged beauty.

John Haines’ short story, Ice, recalls “a deep swallowed sound, as if the river had ice in its throat” thus marking the transition from ice to water. Here too there is something of the greed of mankind. Salmon are fished in the shallow streams with a gaff-hook: “If the fish happened to be a female heavy with eggs, the eggs sometimes spilled through the torn sides of the fish, to lie pink and golden in the freezing snow… There was something grand and barbaric in that essential, repeated act.”

At this point in the journal, stones appear alongside the water. In The Original Light by Mark Valentine, a boy swaps all of his football cards for a marble – “a real marble, not a glass toy: a globe of streaked colours whose peculiar hues I particularly wanted”. The boy inhabits a landscape in flux. Old houses are left abandoned, a child is raised with an uncle and a cousin, and the name “Mordecai” is the only clue as to what may have befallen the missing family members and neighbours. Peter Haynes’ Stone takes us to a dystopian future in which the once-fertile land becomes barren, after a giant rock that floats above a divided kingdom [which has something of Palestine and Israel about it] blots out the sun before splintering into shards, obliterating everything on which it falls.

Religion, religious practice, the evidence of belief and the consequences of its presence run alongside the elemental progression through the journal. In Another Light Philip Baber tells us “walking had become for me a form of contemplation”. Peter O’Leary reminds us that Aristotle saw the stars as the “celestial manifestation of creation’s bright, terrible power… At root, this manifestation must include the earth”. There is an attempt, throughout the journal, to explore what exactly it is that we are all a part of. There is a constant search for connections. Despite the totems that wander through its pages – the wolf, the salmon, the caribou – the voices preserved in Reliquiæ are inescapably human. The desire for understanding, the union that the voices seek is often expressed in the vocabulary of the mystics: Sufism, the early Christianity of the anchorites, the mountain Buddhism of Tibet. Perhaps it’s not surprising, therefore, that in the final pages of the journal, Reliquiæ shifts through water, via the process of evaporation, to clouds. I found myself thinking, more than once, of the fourteenth century anonymous guide to contemplative prayer: The Cloud of Unknowing, which stresses the importance of surrendering the self, and trusting the unknown. Don Domanski’s Bestiary of a Raindrop captures the essence of that text: “there is no self in all this movement / there is no end to this beginning.”

By the last pages of the journal, birdsong begins to appear, and although there is hope in the song of the birds, there is also the implication that the new spring might be one without a human witness. Reliquiæ ends with these words from a translated Inuit tale from Quebec: “Although we heard much from our forebears we have forgotten a lot and no longer know much. This story here is ceasing to be known; here we have heard it just poorly told”. Perhaps, in relation to this last story, that may be true, but the narrative that unfolds throughout Reliquiæ Four is exquisitely told, tenderly constructed, and lovingly made.