In the first instalment of a new column centred on the River Taff, Helia Phoenix explores Cardiff’s dockland history, and the various names for her neighbourhood

Looking on maps of Cardiff before the Industrial Revolution, my neighbourhood is a barren wasteland. Between the mercy of the sea water and the edge of Cardiff, it has no defining architectural features – it’s just labelled as “Salt Marsh”, or “Mud”.

Things have changed a lot since then. There are streets here now. The houses have numbers and postcodes and everything, but it’s often hard to explain where I live to other Cardiffians. It’s a small residential area, right next to the River Taff: a grid of streets, six in parallel, a few more adjoining them. There’s no thoroughfare, no shortcut to anywhere other than the deserted park, or the mental health day clinic. I can only successfully explain my location in relation to the orbit of local landmarks: go past the police station. A few hundred metres from the Millennium Centre. Last left before the bridge that goes over to Grangetown.

My neighbourhood actually has several names. Estate agents will tell you I live in the glossy, fabulous Cardiff Bay. My neighbour Lisa – in her late forties, born and bred in the area – calls it, simply, “the Docks” (as do most of the people in a Facebook group I recently joined called Cardiff Docks Remembered). You may have heard the place referred to as Tiger Bay: the romanticised, mythologised, and mostly long-gone home of Shirley Bassey et al during Cardiff’s Industrial Revolution-era boom, but the real Tiger Bay was actually half a mile or so from where I am. For administrative purposes, the electoral ward is Butetown, but the beating heart of Butetown really lies north east of here: in the same spot that Tiger Bay died.

My favourite name for the place is one that exists as a twinkle of detail, recalled in tales told by parents and grandparents. I love calling the place Rat Island, but in the years I’ve spent trying to find the definitive truth behind the nickname, I’ve never managed to pin it down.

As urban areas start to form around Cardiff’s docklands in the 1800s, the area where my home will eventually be built stays bare. Even when the Sea Lock is built (the ship canal that gave seagoing ships access to the Glamorganshire canal), you can still see the empty peninsula jutting out between the Sea Lock and the Taff.

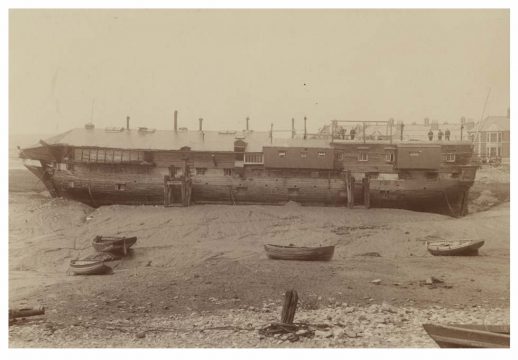

Towards the end of the 1800s, the area found purpose thanks to Dr Henry Paine, Cardiff’s Medical Officer of Health. He was responsible for controlling infectious diseases in the city (tough shout contending with thousands of sailors coming into the docks, riddled with everything from typhus to cholera and beyond). The answer was Cardiff’s Seaman’s Hospital, a frigate named HMS Hamadryad, towed up from Devonport in 1886, converted into a hospital and eventually dragged ashore to her new home: the badlands of Rat Island.

(Image courtesy of Cardiff Central Library via People’s Collection Wales)

(Image courtesy of Cardiff Central Library via People’s Collection Wales)

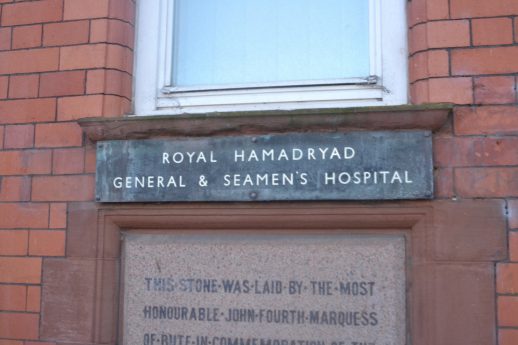

The Hamadryad Hospital Ship was funded by a levy on coal passing through the docks, and over its lifetime, this earth-bound maritime goliath treated 173,000 sailors and locals (incredible when you consider the population of Cardiff in 1901 was 164,333). Conditions on the hospital ship were cramped, so a new, bricks-and-mortar hospital was built to replace her. This opened in 1905 (remarkably, it still stands), and HMS Hamadryad was towed away to be broken up. She’d been ashore for so long, a channel had to be carved to take her back out to sea.

But where are the rats in all of this? It’s a good question. One explanation for the area’s name is that thousands of rats escaped from the ship when she was first hauled onto land; another, that they escaped when she was being dragged back out to sea for her final voyage. I also read that the rats had always lived there, in their perfect, natural habitat. Local writer Peter Finch has probably researched the city more than anyone else, and he offered me this: the island was formed following one of the periodic floods that plagued the Taff. Gulls and other birds nested there, rats invaded along a revealed at low tide causeway in order to steal their eggs. The land became infested and the name followed.

But those are all just versions. Plausible, sure, but I want truth. These days, there are no signs of the eponymous rodents. My obsessive Googling and trying to chase the little buggers around the internet is a bust. Members of Cardiff Docks Remembered can’t definitively tell me how Rat Island got its name, and historians and academics offer nothing substantial either.

For additional research, I decide to walk around the place, an area that now comprises parkland, new flats and Victorian housing, looking for some real live rats in the wild. When I set out on my walk, I’m addled. News and current affairs are keeping me up at night, and I’m cranky. £350 million a week for the NHS. 90 day immigration bans. Climate change. Islamophobia. LGBTQ rights. I’ve had to stop reading the news and spend less time in the social media echo chamber. Every new piece of information brings so much confusion or disappointment or anger that I’m having trouble sleeping.

I work my way through the park, distracted by abstract concepts that I can’t do anything to influence. Equality. Freedom of speech. What will happen to rural communities if Wales loses all its farming subsidies. I’m not in a great mood for nature spotting.

I step under the A4232, the dual carriageway that joins the south of Cardiff with the M4. It is supported by giant concrete struts, and sends commuting traffic flying high above my head, over the Taff and on to final destinations. You could hardly call the view a beautiful one, but there’s something about it that always makes me stop and look.

Hamadryad Park is full of undergrowth to hide in and there’s plenty of food and rubbish on the floor, pulled from the bins by gangs of angry seagulls. It should be the perfect ratty habitat. I slowly loop around the park from the wetlands, passing the ghost of the old Sea Lock and around where the Hamadryad used to be perched, trying to visualise the hulk of the hospital ship on muddy flats ahead of me. All I can see is a children’s play area and a basketball court. Annoyingly, it occurs that my quest for definitive truths will remain unfulfilled.

An old lady in a red coat limps slowly past me, with a tiny pug trotting alongside her. She’s pushing a pram. I do an actual double take when I realise the pram has another tiny pug sitting in it: he’s fat and hairy, and has a touch of Yoda about him.

The lady notices me staring, and smiles. I smile back. Her dogs are the closest things to rats that I’ve ever seen – and probably will ever see – in this park. That will do, I think, and head home.

*

Helia Phoenix has written for Rolling Stone, The Guardian, and Kruger Magazine, and now runs the We Are Cardiff project. Look out for further instalments of her column in the coming months, but in the meantime, why not take a peek at her website or follow her on Twitter?