Robert Macfarlane introduces a new edition of Clarence Ellis’s ‘The Pebbles on the Beach: A Spotter’s Guide’, published today by Faber & Faber.

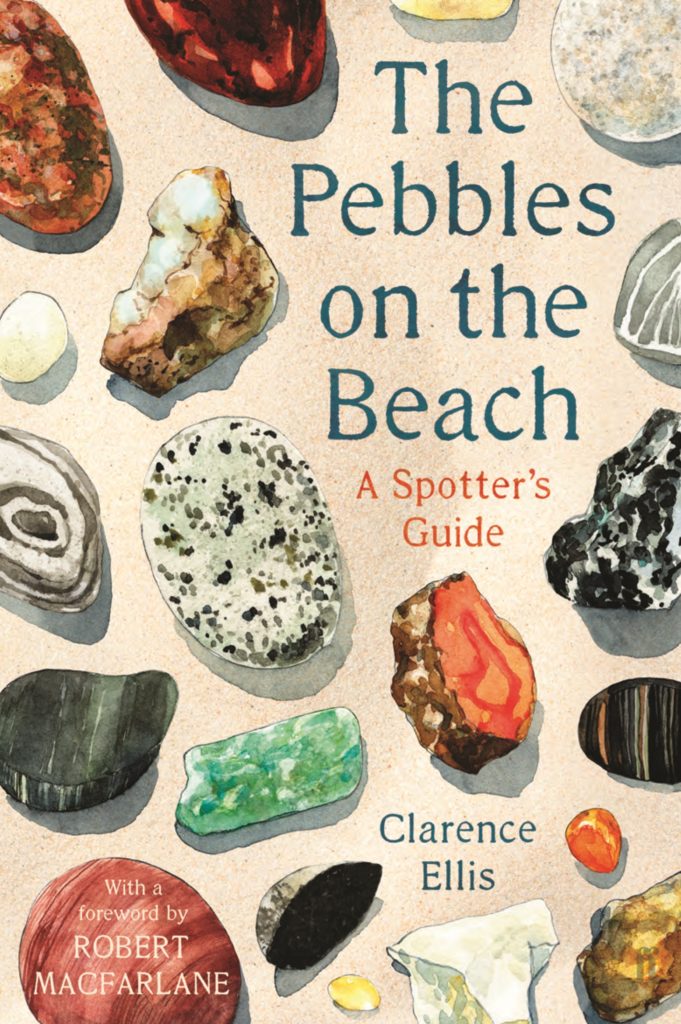

Clarence Ellis’s The Pebbles on the Beach was the stone book of my childhood. I first pulled a copy of the Faber paperback off the shelves of my grandparents’ house in north-east Scotland when I was perhaps ten or eleven, by which age I was already – like most children – a passionate lover of pebbles. So too were my grandparents. Their cold house near the Cairngorms contained hundreds of stones that they had picked up around the world, many kept in water-filled bowls in order to preserve their lustre. They even constructed a wall-mounted cabinet with tiny white-wood compartments, each of which held a different object: a pine cone, a cowrie, a rupee, a geography cone shell (once deadly, now dead), and rows of polished pebbles, the lovely names of which they tried to teach me: chalcedony, onyx, jet, moss agate . . .

In my grandfather’s garage there was a stone-polishing machine that clearly possessed, to my young mind, magical powers. Into its barrel we would heap handfuls of dull pebbles gathered from the riverbank at the bottom of the garden or the beaches of the Moray Firth. Then my grandfather would fill the barrel with water, add a measured concoction of sands, cap the barrel shut, and set it grumbling away. Days later we would return to the garage and watch as he uncapped the barrel, poured away the water, rinsed the contents of its grit – and then tipped out onto a workbench a slew of stone-jewels: glowing green serpentine, red jasper, glossy pink Cairngorm granite, glinting with mica flecks, and little white eggs of quartz. How had this transformation happened? Even the brown flints that we took from the shingled driveway of the house became miraculous after polishing: their craquelure showing clear, the cloudings and translucencies of their surfaces resembling maps or planet-atmospheres.

Ellis’s wonderful book became my guide to the finding and the making of these pebbles, and his writing was also one of my first encounters with what I now think of as ‘deep time’ – the aeons of earth history that stretch dizzingly away from the present, humbling the human instant. As Jacquetta Hawkes – the visionary author of A Land (1951), a deep-time tour of the making of the British landscape – put it in her appreciation of the book’s first edition: ‘Mr Ellis writes simply and well about the natural processes which compose, shape and transport pebbles’. Indeed he does, and that simplicity – or calm clarity – is one of this book’s durable qualities. I valued then, and still do now, the manner in which Ellis approaches his subject from first principles (‘What is a pebble?’ ‘How have raised beaches come about?’), and the hint of moral duty with which he infuses the study of geology and geomorphology (‘We paid some attention to sandstone in the last chapter, but we must examine it more closely’). I still prize the insider tips he offers: that serpentine discloses its identity by means of its ‘wax-like lustre’, or that if you break a quartzite pebble ‘into two pieces and strike one against the other in darkness’ there will be an ‘orange-coloured flash’ and a ‘not unpleasant but very difficult to describe’ smell.

So Pebbles became the book that we took as a family when we went ‘pebble-hunting’ on the coasts of Britain: wandering bent at the waist along the beach, eyes peeled for rough orbs of agate, quartz prisms, purple jasper and elusive amber (so hard to tell in its unpolished form from the flints among which it usually lies). It was also the book that accompanied thousands of other families to the beach; lodged in glove-boxes, stuffed in rucksacks. And thanks to this new edition, it should now find a fresh generation of readers, nearly sixty-five years since its first publication in 1954. ‘Mr Ellis has solved that difficult problem of what to do at the seaside when the weather is against sun-bathing: collect pebbles,’ ran the opening line of a review of the book in The Spectator that year. Well, quite.

Ellis’s popular work can be seen, I think, as a quiet addition to the surge of high-quality, British natural-history writing that followed the years after the end of the Second World War – above all the New Naturalist series, the first volume of which was published in 1945. The New Naturalist project tasked itself with interesting the general reader in the wildlife and ‘scenery’ of Britain by uniting the scientific knowledge of professional naturalists with a commitment to communication and evocation. Ellis’s prose shares its traits with the best of the New Naturalist writers. It is lucid, patient in its explanations, and hospitable to all-comers. He relishes his subject across its aspects: this is an expert speaking to amateurs, but also an enthusiast seeking to ignite enthusiasm in others. ‘Every pebble is of some interest,’ he declares, democratically, brooking no argument. Reading his book is rather like taking a lesson from a charmingly earnest, slightly awkward and impassioned geography teacher. There are some very funny Pooter-ish moments – and some bright flashes of illumination.

Ellis loves words as well as pebbles. It was he who first broke open the language of stones for me. He strikes names against roots to produce flashes and smells: ‘Gneiss (pronounced “nice”) is a word of German origin, derived from an Old High German verb gneistan, “to sparkle”. In sunshine, especially after rain, it certainly does sparkle, as it is a highly crystalline rock.’

‘Schist (pronounced “shist”) is derived from a Greek word schistos, meaning “easily split”.’ Ellis evidently admires language for its capacity to grade and sort the world – but also for the poetry it carries. As an ordinary-looking pebble can be sliced and polished to reveal dazzling patterns, so, in Ellis’s hands, can a word. Here you will learn (if you have already forgotten them from Geography GCSE) ‘swash’, ‘backwash’ and ‘fetch’ as the terms necessary to help understand ‘the rudiments of wave action . . . upon the movement, the shaping and the smoothing of pebbles’; you will meet ‘swales’ and ‘fulls’ as being respectively the ridges and hollows of shingle formation on the seaward-side of long shingle banks, and you will be given the word-gifts of ‘crinoid’ and ‘calyx’, ‘piriform’, ‘foliation’ and ‘xenoliths’: the last denoting those stones that have been transported by glacial action far from their origin, often identifiable by the striations (‘Latin: stria, “a groove”’) that show where they had been scraped along by a glacier while ‘frozen into its underside’. Yes, Ellis tumbles words as the sea tumbles pebbles, bringing them into new and surprising relations with one another. In this respect, his book stands as a shy and bespectacled cousin to Hugh MacDiarmid’s extraordinary long poem ‘On a Raised Beach’, published twenty years before Ellis, and written in a mixture of synthetic Scots and geological baroque. ‘All is lithogenesis . . .’ starts that poem, famously, fabulously, before beginning its shingle-litany: ‘Stones blacker than any in the Caaba,/Cream-coloured caenstone, chatoyant pieces,/Celadon and corbeau, bistre and beige’.

About the only sentence of Ellis’s book that puzzled me on first encounter, and still puzzles me, is its third: ‘Collectors of pebbles are rare.’ Really? For as long as I could remember, my parents and my brother and I had picked things up as we walked. Surfaces in our house were covered in shells and pebbles. We didn’t seem to be too weird, at least as far as I could tell at the time, or particularly ‘rare’. Pretty much everyone I knew, in fact, seemed to gather pebbles and line them up on window ledges and mantelpieces – performing a humdrum rite of happiness and memory-making. Spot, stoop, hold in the hand, examine, slip in the pocket to carry home. This was the way of our British beach holidays when I was growing up, and I think it is still the case now. Children are natural treasure-seekers, and pebbles – like conkers – are natural treasure.

One of my favourite words from Douglas Adams and John Lloyd’s The Meaning of Liff – their brilliant comic dictionary which takes British place names and matches them to feelings, objects or experiences ‘for which no words exist’ – is ‘Glassel’. Glassel is a village in Aberdeenshire (not far from my grandparents’ house, as it happens); it is also, at least in Adams and Lloyd’s genius definition, a noun meaning ‘A seaside pebble which was shiny and interesting when wet, and which is now a lump of rock, which children nevertheless insist on filling their suitcases with after the holiday.’ Clarence Ellis’s The Pebbles on the Beach is a praise-song to the humble ‘glassel’, which keeps them ‘shiny and interesting’ long after the holiday is over. ‘With understanding will come still greater enjoyment,’ Ellis concludes his introduction. Just so.

Cambridge, 2018

*

THE PEBBLES ON THE BEACH: A Spotter’s Guide, by Clarence Ellis, is published today by Faber & Faber (£9.99).

We have 3 copies of the book to give away on this week’s newsletter. Make sure you’re subscribed to our mailing list before 11am tomorrow.