In light of a book of photos collected by Jochen Raiβ, Lulah Ellender considers the affinity between trees and women

A woman stands on stumps of chopped branches, one knee raised and a hand behind her head, in a pose more suited to a swimwear shoot on the beach. She’s looking away from the camera, not quite in the tree but perched uncomfortably on the edges of it. It looks like some kind of pine tree, spiky and unforgiving.

A woman is slung between the fork in the branches, lying back with something behind her head and underneath her legs – a coat maybe? Her skirt is hoisted high, revealing a bare thigh and a whisper of a dimple. Her hand, planted on her thigh, reveals an engagement or wedding ring. She wears battered brogues and looks windswept.

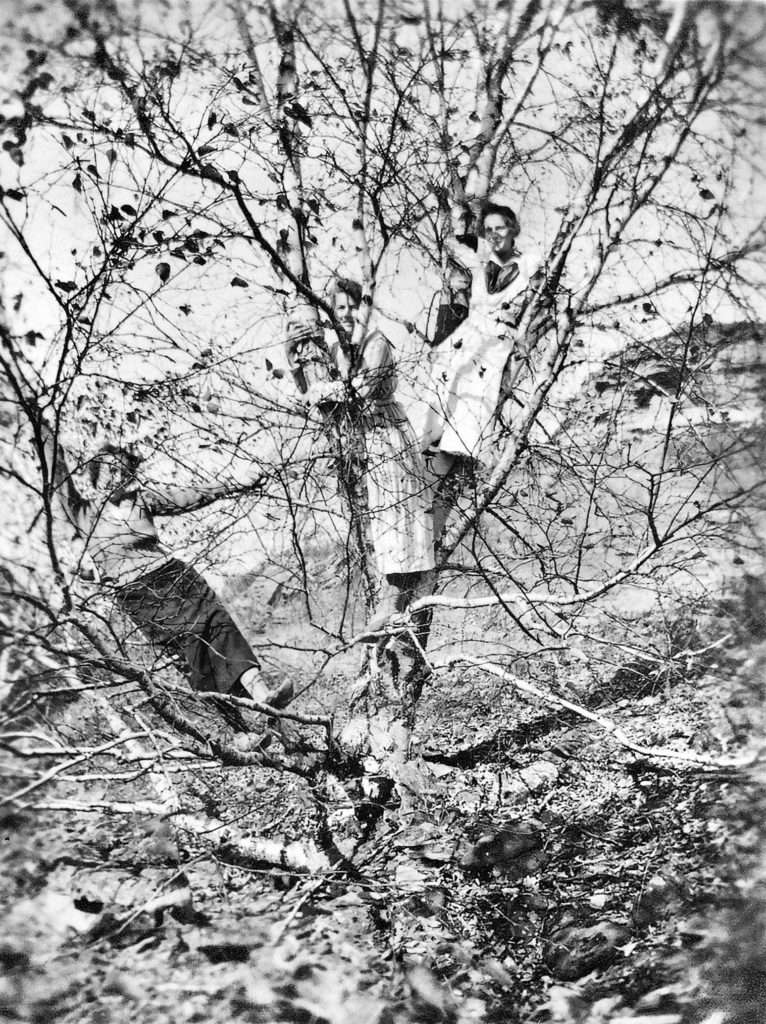

Three women, all wearing long dresses or skirts, stand in a spindly tree (birch?). The branches don’t look strong enough to hold them. The light and the scattered leaves create the impression that they are part of the canopy. Two look like they are leaning into the branches, supported and easy; the other clings to a bigger branch with a half smile.

A woman in long skirt and heels clutches awkwardly onto a branch with a secure foothold for one foot, but the other rests uneasily on the stump of an old limb, a scar. She is smiling, but it could be a grimace; her body is angled away from the tree. I can’t see how she will get down other than by jumping.

A glamourous woman reclines on a long, low branch reaching out over a river or lake. She is partly obscured by leaves. Her feet are bare and she wears a big smile, as if she is what she’s doing is thrilling and spontaneous. But there’s something odd about the angle of her elbow – a forced relaxedness, and her hand is cupping the tree as if for support.

These are all photographs from a book called, helpfully, Women in Trees. This small, wonderfully strange book contains images collected by photographer Jochen Raiβ, all discovered in Germany in flea market shoeboxes full of unknown faces and untold stories. The photographs span a timeframe roughly from the 1920s-50s, although most are not dated and have no names. We, like Raiβ, can only guess at the stories behind them. We, too, want to know what it was about that particular moment that made the women climb up into a tree. And most of all we want to know who took the shot.

The phrase ‘taking a shot’ immediately turns these women into birds, observed and hunted by an anonymous presence, taking refuge in the canopy. What seemed at first glance to be joyful reclamations of a childhood freedom and playfulness now seem to be something else entirely. What power this unknown cameraperson – probably cameraman – wields.

These women are often wearing nice dresses and heels. Not obvious tree-climbing gear. Did they want to be up a tree? Were they out for a picnic with friends when one of them dared another to see how high they could go? At a time when the space women took up was tightly controlled, perhaps they wanted to perch in another dimension for a moment.

Like the girls who took part in a 2018 research project at Dalhouse University exploring gender and health through taking photographs of their experiences of exercise posing in non-stereotypical natural surroundings, maybe they were playfully subverting gender-normative expectations of female behaviour. I find a video of a 97 year-old woman climbing barefoot up a tree, as nimble as a monkey, joyful, at home in the space. I remember my mother showing us the tree where she would sit as a child with a book and an apple, reading alone for hours. Writer and gardener Alys Fowler describes the importance of trees in helping her deal with life: ‘I’d climb trees to hide among their boughs. I’d be so quiet and hidden that nature flooded over me and I’d find extraordinary peace as all the molecules in my body sighed back to the places they’d come from.’

Our ape ancestors also sought refuge up in the trees, and analysis of the arm sockets of a 3 year-old girl’s fossilised skeleton from 3.3million years ago showed that we were still climbing trees whilst also walking upright. Yet, what defines us as a species was coming down from the canopy. Although humans no longer live in trees, our history (and our future) is entwined with theirs. We know that trees communicate through underground mycorrhizal networks. We also know that they can differentiate between types of saliva if they are bitten or attacked, and that they can group around an ailing tree and provide it with sustenance. These characteristics – nurture, talking, sharing, creating community – are also traits often assigned to women. Is there an affinity between trees and women?

For thousands of years we have depended on trees for safety, tools, parchment and fuel. We turn to forests and woodlands as a retreat from modern life. Yet these places are also full of fear and darkness. Forests are liminal spaces where we also go to hunt, to cruise, to fuck, to lie in wait. This duality of safety/danger mirrors the conflicting feelings I have when looking at the photos in Women in Trees: maybe the women are joyfully communing with Nature; but maybe they are trying to keep themselves safe from an unseen menace that lies beyond the frame.

Katherine Mansfield also saw a potential malignancy in trees, describing them as mysterious forms that ‘might have claws instead of roots.’ This contrasts with Virginia Woolf’s description of Septimus Smith’s rapturous oneness with the trees in Regent’s Park: ‘…the leaves were alive; trees were alive. And the leaves being connected by millions of fibres with his own body, there on the seat…’ This Modernist implication of ourselves in the perceived object echoes much earlier representations of women and trees in mythology and folklore. Many of these stories contain a transformation, blurring the distinctions between gods, humans and trees.

Turning from photographs to paintings, we can explore these ancient entanglements and transformations through representations of myths. Take Santi di Tito’s The Sisters of Phaeton Transformed into Poplars. This painting shows the naked Heliades, sisters of Phaeton, who have just discovered their brother’s death. These nymphs turn into poplar trees and their tears become amber. They are shown covering their eyes in sorrow, hands and hair sprouting leaves and branches, all blown in the same direction as the clouds, creating a sense that they are becoming part of the natural world. In Franceschini’s The Birth of Adonis we see Myrrha, who has been impregnated by her father and metamorphosed into a tree either as punishment or as protection. Her agonised face is raised skywards and there is a violence to the upward movement of her arms and hair, which have become branches and leaves. Two women point to her pubic area, now covered in bark, from where the baby Adonis has just emerged. Bernini’s extraordinary sculpture of Apollo pursuing Daphne depicts another transformation of a woman into a tree. He has captured the moment Apollo catches Daphne, whom he has pursued in unrequited lust since being struck by cupid’s arrow (itself made of wood?), his hand touching her side. The marble is full of momentum and energy as the bodies twist and flow, Daphne’s fingers and hair now delicate leaves, her flesh beneath his hand hardening into bark.

Consider also the sinister origins of the swing – an everyday object that symbolises carefree childhood games, but which apparently comes from the story of Erigone, who hanged herself in the pine tree under which her murdered father, Icarius, was buried. She cursed many young girls to be hanged in the tree until justice for her father was done. Her story was celebrated in the ‘Vintage Festival’, with offerings to Erigone and her Icarius, masks hanging from trees and girls on swings beneath the branches. In this story the tree becomes a weapon rather than another state of being. This story reminded me of writer Sue Townsend recounting how as an 8-year old girl she witnessed the brutal murder of a young girl whilst she was high up in the branches of a tree. She had hidden up there watching the girl die against the tree trunk, frozen with fear, before trying to alert an adult.

Other narratives similarly portray women’s complex relationships with trees. The Christian creation story centres around an apple, grown on a tree in the Garden of Eden. It is Eve who persuades Adam to eat the apple, and precipitates the Fall. In the Indian Flowering Tree story a girl switches between human and tree forms in a tale that speaks of the disorder and violation, but ultimate cyclical regeneration, of Nature. The European folktale The Three Oranges has three beautiful maidens hidden inside three oranges, and the Japanese Green Willow describes how a man tends three stumps of trees that had been the other-states of his wife and her parents. I’m reminded of that photo of the three women in a tree, a triplet ripple from these stories. An African San tale, The Woman Who Was Turned into a Tree, tells of twenty naked women swimming in a river. A man, who has eyes in his feet, arrives and sits on a dress belonging to one of the women. To get the dress back she must bring him thorns, but when she follows his instructions he throws the thorns into her skin. She becomes a thorn bush until she is discovered and transformed back by the god Heiseb.

Contemporary performance artist Joan Jonas recently interpreted the Grimm fairy tale The Juniper Tree using red and white images of contorted faces to represent the story’s central character’s wish for a child as white as snow and as red as blood. A kimono hung from a wooden frame depicts the stepmother and tree. In the story the woman gorges on junipers and has a baby before dying. She is buried under the juniper tree and witnesses the violent murder of her child by his stepmother. The juniper tree is the embodiment of the dead mother and represents righteous redemption. In Merce Rodoreda’s Death in Spring dying citizens are buried alive in trees, their throats filled with cement. These disturbing connections between trees and people reflect what Sara Maitland describes as a ‘profound sense that violence, beauty, risk and joy are inextricably tangled together; and the roots lie in the forests.’ Trees contain a deep magic. Perhaps our women in trees knew this, felt it on an ancestral level, as they perched amongst the branches.

As well as these ancient connections there’s also something sexual about women and trees. Could this be due to the phallic thrusting of a tree heavenwards, out of the earth? I remember the raped and subjugated women in post-war Germany and wonder if perhaps the photographer found it erotic seeing them straddling the branches. I read an article about a woman called Emma McCabe who apparently wants to marry a poplar tree she’s named Tim. In a possible manifestation of ‘dendrophilia’ (sexual attraction to trees) she is quoted as saying it’s ‘the best sex she’s ever had.’ Another woman flies to England from Canada every year to visit one particular tree she believes is her soul mate and that she feels she has an energetic connection with. Women have long protected trees, though not usually for romantic or sexual reasons. In the 1730s in India the Bishnoi women surrounded a group of trees to stop them being felled. Around 353 women were killed as a result of the protest. Women in Oaxaca, Mexico are ‘marrying’ trees as a symbolic gesture of mutual protection and to prevent illegal logging.

Mary Vidya Porselvi writes that, ‘When women are in trouble they find refuge in trees. When trees are in trouble, women form a group and protect them.’ I think this might be at the heart of the photos of these women: both women and trees have at times been exploited and objectified; both offer mutual solace and protection. With the recent UN warning that we have less than 12 years to prevent a climate catastrophe, spending time with trees – time in Nature – is increasingly important. To want to save it we need to experience it. Our own knotty roots are tangled with those of the trees. Perhaps there will come a time when humankind has long disappeared and the planet has rewilded. The trees will hold our stories.

*

Lulah Ellender’s book Elisabeth’s Lists: A Life Between the Lines is published by Granta and is available to purchase here. You can keep up with her work via Twitter or her website.