In Vienna, Adam Scovell visits a café haunt of the novelist, playwright and poet Thomas Bernhard — and heads off the beaten track in search of his grave

“I prefer to be alone. That’s my ideal condition,” the writer Thomas Bernhard once suggested. “My house is really a great prison. I like bare walls. Bare and cold. That’s best for my work.” He was discussing the complicated relationship he had with his country house in Obernathal near Gmunden in Austria, a retreat away from general Austrian society which he famously loathed. It was a loathing that dripped regularly onto his pages. Just like the narrators of his novels, such as in Correction (1975) or Extinction (1986), Bernhard is an enjoyably contradictory persona, annihilating the things he seemed to enjoy as much as things he hated. In spite of inhabiting the isolated house since 1965, the writer’s relationship with the country’s bustling capital of Vienna is equally as intriguing, equally as complex and equally as contradictory. Both of these extremes of place – the isolated rural and the bustling cosmopolitan – inhabit the same prose, the same mania.

Far from locking him in solitude, Vienna was another kind of prison; one built on the damning mixture of bourgeois sentiment, conservative Catholicism and the still persistent remnants of the country’s association with National Socialism, especially in the upper echelons. But understanding Bernhard’s work is equally about understanding Vienna, its coffee culture, its hang-ups and ticks. Even if regularly isolating himself in his own “memorial dungeons” in the country, Bernhard was a writer who reacted to the city as much as to the country.

Café Bräunerhof

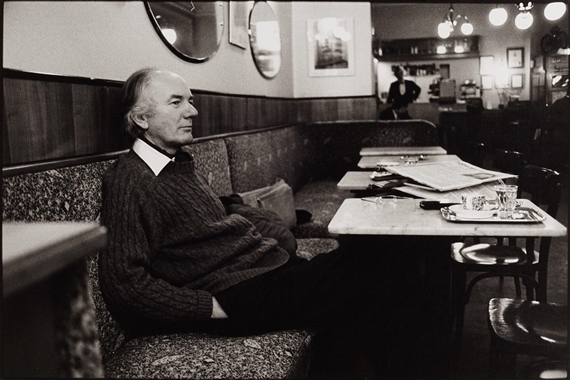

Bernhard’s array of novels glistens with a very particular vitriol. He smuggles in veiled attacks of his own in the form of character monologues, though they are only partly hidden, such is their aggression and rage. Vienna is still famed for its literary café culture and Bernhard was a large part of its image in the post-war years, even if he seemed to rally against it every turn. A number of cafés in the city have a string of literary associations but it was Café Bräunerhof that drew Bernhard. Search for images of Bernhard online and one of the first that appears, outside of those taken in his country house, is one taken in the historic café, relaxing on the corner seat with a coffee and an array of newspapers. Yet what did he write about his favourite café in his works? A segment from his novel Wittgenstein’s Nephew (1982) illustrates Bernhard’s biting contradictions perfectly:

“The literary coffeehouses have a foul atmosphere, irritating to the nerves and deadening to the mind. I have never learned anything new there but only been annoyed and irritated and pointlessly depressed… At the Bräunerhof, above which my friend had lived for years before we met, I am still put off by the foul aim and the poor lighting, which is kept down to a minimum — doubtless from perverse considerations of economy — and in which I have never been able to read a single line without effort. I also disliked the seating, which is inevitably damaging to the spinal column, however briefly one sits there — to say nothing of the pungent smell that emanates from the kitchen and very soon get into one’s clothes. Yet at the same time the Bräunerhof has great merits, though these do not suffice for my peculiar purposes. These consist of the extreme attentiveness of the waiters and the unfailing courtesy of the proprietor, which is neither exaggerated nor perfunctory.”

As typical for Bernhard, it’s difficult to tell whether he actually liked things or not. His manic rage dominates all. The negatives induce a burning hatred; the positives elicit an almost transcendental respect. Nothing is safe from his critical eye, not even himself or the world of literature he inhabited. Yet neither is anything safe from his heart, his overriding joy at the strangest of pleasures. His is a writing that is warmed by the friction between this rage and joy. Bernhard is unsparing in his adorations and his hatreds which makes him refreshing like strong coffee on an early spring morning. Nothing is done by half.

Visiting the Café Bräunerhof, it was difficult to know what to expect. The Trip Advisor comments displayed as equally a dismissive attitude as Bernhard’s narrator. If some were to be believed, the waiters – with their black suits, bow ties and silver platters – were Bernhard-esque characters themselves, cold shouldering and ambivalent, almost insulting even. It would have been positively Bernhard-esque to be insulted by a waiter at the Café Bräunerhof. They were all, of course, wrong. Café Bräunerhof is a time-capsule like many Viennese cafes. There is no music – except live at weekends when quartets gather to play a brief classical repertoire – no Wi-Fi, and very little light. The furniture is exactly as in the photographs of Bernhard sat there and the newspaper holders are even the same battered type.

I sat down in a seat nearest to the door and below a photograph of Magda Schneider (mother of Romy Schneider), the seat in fact which Bernhard is slouched on in the picture. I ordered a coffee, soon arriving on a silver platter with the famously extravagant Viennese foam bubbling atop, and watched the other drinkers idling around. A girl sat next to me reading a novel by Robert Musil, a pair of older men were debating in German about a story in one of the newspapers whilst sipping water mixed with spirits, and an American academic chastised her fellow drinker about how her research on Gustav Klimt had been appropriated without her consent for an exhibition booklet. It was, in other words, exactly like sitting in a novel by Thomas Bernhard. “Yet for many years it was at the Bräunerhof that I felt at home,” Bernhard’s narrator later admits again in Wittgenstein’s Nephew. It is a telling admission.

Grinzing

Bernhard was a writer full of surprises. He infamously stated in his will that his huge backlog of plays and novels were to not be published or performed in Austria after his death, since rescinded by his estate’s executor in the 1990s. Equally surprising is to find that he was buried not somewhere near his retreat in Gmunden but in Grinzing Cemetery just outside of central Vienna. After a morning spent in Bernhard’s favourite café, it only felt right to make the pilgrimage to his place of resting. Taking the U-Bahn to the end of the line to Heiligenstadt, I went in search of the graveyard.

Grinzing is an unusual place, a mixture of imposing housing blocks and then an array of affluent streets and the suburbs as the incline of Lower Austria and its dark forests begins. Walking out of the station and along, I was surprisingly greeted by the housing block used by Liliana Cavini in her controversial film,The Night Porter (1974). The flats were in fact the home of Dirk Bogarde’s ex-concentration camp officer. But soon these buildings faded into hills with much older, more lavish buildings and houses. People disappeared as if kept away by the vertical sway of the roads. I followed a bin lorry all of the way up the final road to Grinzing Cemetery, itself camouflaged by a minor housing estate. Bernhard’s grave, in spite of being there since 1989, was not on the map unlike most of the other notable company he shared, including that of Gustav Mahler.

I walked and walked until finding what I knew to be his grave, drenched in green ivy with intricate metalwork growing out of the greenery. There were only a handful of totems left by other devotees of his writing, nowhere near as many of other writers’ graves I had visited. Marguerite Duras, Marcel Proust, J.G. Ballard: even the darkest of writers had an array of pens, coins and debris left by their admirers. Bernhard’s prose defends his grave from such sentimental ephemera; his life was one long toying with death until his assisted suicide. Leaving objects of affection feels trite and almost contrary to what the writer would have wished. “Everything is ridiculous when one thinks of death,” as he once suggested when winning the Austrian national prize for literature in 1968; of all the times to choose to admit such a philosophy.

Instead of leaving a memento, I took a Polaroid of his grave, the leaves shining in the sunlight. The view back towards Vienna was in sight above the buildings and it felt just the right distance away for a writer who wrote such biting criticisms of the city. I sat for a while in the surprising warmth of early spring, listening to the hooded crows argue and content with their company alongside the dead writer. “You are never truly together with one you love until the person in question is dead and actually inside you,” wrote Bernhard in his novel, Gargoyles (1967). Never was a truer word written. Bernhard died the day before I was born, his mania dissipating into the atmosphere. But it lives on, I hope, whether in those seeking the mathematical perfection of buildings in forests, in those desperate for the Gouldian transcendence in performances of Bach, or in those trekking for miles on lonely visits to the gravesides of writers long since crumbled into the ground.