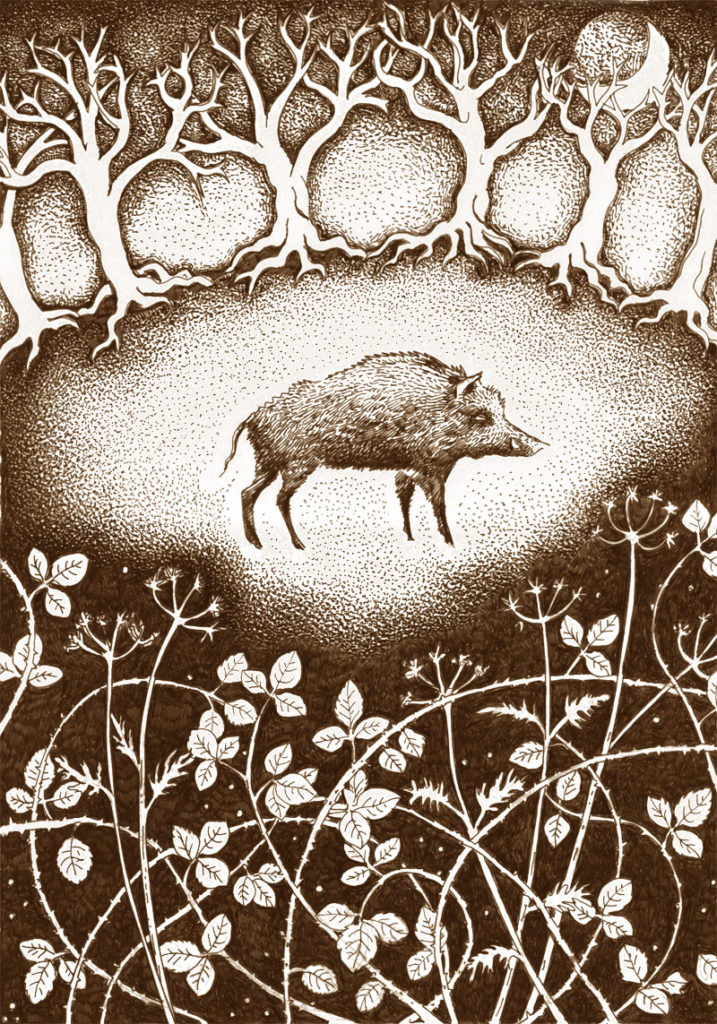

Writer and illustrator Alexi Francis heads to the Forest of Dean, in hope of crossing paths with some of its notorious thatch-coated residents

It doesn’t take long to walk from the cottage up through the Turkey oaks and larch into Flaxley Wood. On the way I linger, and catch the papercut silhouette of a roe buck between the trees. Stock still, I wait and watch, hardly daring to breathe. He browses on leaves, strips some bark then moves slowly between the trunks. I can see his finely tined antlers, his slender head and neck, and can just about make out the dark oval of his right eye in the evergreen shadow. Then he looks in my direction. Unsure whether I am there or not, he hesitates, shifts his head a little, but he doesn’t flee. He just turns and gently makes off into the tangle of undergrowth.

Reaching Flaxley Wood I stride uphill as quietly as I can, periodically inspecting the mud beside the track for animal prints. My main hope is to see wild boar.

The wood is located on the edge of the Forest of Dean, well-known for its large wild boar population; estimated to be over a thousand. They were driven to extinction in the UK back in the middle ages. There followed various attempts at reintroducing them. Then, in the 1980s, a few boar escaped from boar farms. Some were deliberately introduced back into the wild and small populations became established in the south east and south west of the country.

My first introduction to wild boar was reading Asterix books as a child. Asterix and Obelix always seemed to be spit-roasting the ubiquitous boar of the forests of Gaul. It was much later, while on holiday in Portugal, that I had my first, brief, sighting of a boar – the back of a large rufous animal slinking off through the cane grass.

Where the track forks I find fresh boar prints in the mud – two bean-shaped cleaves about two inches long with dewclaw marks just visible. They have been here, but I don’t see any this evening. Tomorrow I will visit the main forest to see if I have any luck there.

*

It’s the following day and I’m with my partner Kevin in the Forest of Dean. We’re following a vague trail through an area of young birch, well away from the main tracks. There are signs of boar everywhere – churned up earth, scattered bluebells and wood spurge in disarray. Boar rummage in the earth looking for roots and worms in a similar way to badgers. They also eat young leaves, nuts, fruits and whatever they can find. In the Forest of Dean their presence is not always appreciated. Not everyone likes to find their lawn uprooted, their crops raided, the playing fields disturbed. Occasionally it happens.

The trail undulates and meanders through the trees. I notice heaps of brown scat, larger and lighter in colour than sheep or deer droppings. It looks fresh and I guess it belongs to boar. We tread carefully.

Up ahead is a lookout tower, a shooting platform. I ignore the unease I feel about this and we continue walking. Beyond the open birch woodland the terrain slopes down to the muddy trickle of a stream. We negotiate the stream and make our way up through a stand of stunted beech, deeper into the forest.

Dry bracken, bramble, gorse and scrub now surround us. It is quiet; no sound of people or the road. I enjoy feeling a little lost among the chaos of last year’s bracken. The scrub thickens as we proceed further, fresh scat and prints on the bare earth. Some of the vegetation has been fashioned into boar-shaped tunnels or flattened into boar ‘couches’. I’ve learned that they’re largely nocturnal, lying low during the day, and they could be anywhere.

I have often noticed, usually in retrospect, a hush, a subtle change in atmosphere, when a wild animal is close by. It’s the sudden quiet when a sparrowhawk is on the wing and the rest of the birds fall silent. Perhaps I catch a scent that I don’t immediately register as a scent. Or feel a sound almost below the threshold of hearing, like the ominous moment before a storm when the wind dips and there is a faint murmur of thunder. I need to become conscious of these subliminal signs to get into the mind of the tracker.

Suddenly there’s a crash, a scuffle from the gorse and a large boar explodes into the clearing. An image of a stocky build, head, shoulders and earthy thatch of coat – a rush of primal energy. Away it thunders into the trees. Kevin, quiet and alert just ahead of me, declines to continue; we should back off, not follow the boar. We pause, senses heightened, awestruck. Then a second adult boar violently erupts from the bushes and, like the first, charges off into the trees. It is powerful and unnerving; they could have rushed straight into us. Boars have good hearing and an acute sense of smell, but poor eyesight.

We double back, a little startled, away from the thick scrub. After a minute or so, two more boar decide to break cover and rush off out of sight; we realise we were in their midst. I don’t feel in any real danger, but they are wild animals, strong and unpredictable. I can’t help but feel a little euphoric.

It is far from ideal disturbing the boar in this way – in fact it is really quite clumsy. However, I am pleased to have seen them. Sightings are generally quite common, but not so common during the day. We retrace our steps, cross the stream again and find a forest track. A nonchalant family of cyclists passes us by, followed by a dog walker enjoying the warm spring afternoon.

There is a legend of an animal, The Beast of Dean, that lives or once lived in the Forest of Dean. The legend arose after boar became extinct in the UK, becoming better known in the early 19th century. The animal was supposed to resemble a very large wild boar – one capable of bringing down trees and wrecking havoc. Back in 1802, farmers set out to capture the beast, but found nothing. Large animal sightings have always been prevalent; we like to nourish our imaginations with tales of unidentified creatures and monsters. I believe the reason for this is our fear of the wild, the wild dark edge of things – or maybe our love of it. Boar are powerful animals, not to be messed with. Having now encountered them, I think it is no surprise that their presence and power has spurned all sorts of folklore and, perhaps, other, less fabricated stories.

Next time, we’ll go looking for boar at dusk, just when they are likely to emerge. It would feel better to observe them from distant cover, simply going about their business undisturbed – perhaps from that lookout tower.

*

You can read Alexi’s previous Caught by the River pieces here. Follow her on Twitter here.