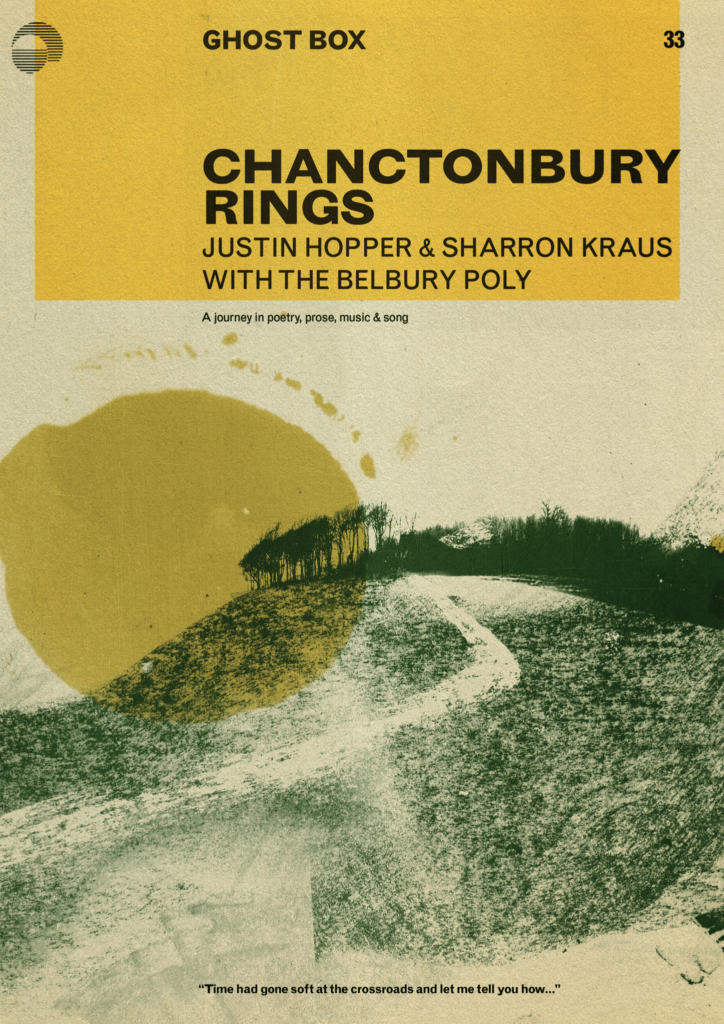

‘Chanctonbury Rings’ is an album of sensual spellcraft, narrated by Justin Hopper, with music from Sharron Kraus and The Belbury Poly. Gareth Thompson delves into the mystic.

With promotional events looming for his 2017 book, The Old Weird Albion, the writer Justin Hopper was feeling edgy. Bored with going to author readings where nothing happened in terms of a performance, Hopper asked the psych-folk musician Sharron Kraus to compose some backing music for him. He sent Kraus the ‘Levitations’ section of his book which deals with cryptic events at Chanctonbury Ring, a darksome copse on the Sussex Downs. Hopper recalls that things soon changed from ten minutes of music, to a full show based on that chapter: ‘Sharron made it so she could perform the various parts alone, with just herself and a guitar, alongside synth, dulcimer, loop pedals; the whole set up.’

At this point, enter Jim Jupp and Julian House of Ghost Box Records, who attended a recital of the show in Steyning, close to Chanctonbury. Jupp says, ‘The live performance had a very emotional impact that’s hard to describe. It’s about a haunting, but it’s not a ghost story. It’s about the landscape, but it’s not the world of nature writing that’s currently popular. It’s more to do with memory and the circularity of things. Even though it builds on an eerie atmosphere, it’s very uplifting and moving.’

A big fan of Ghost Box as an artistic and holistic project, Hopper grasped their offer to record his new venture. The label’s involvement also meant that Kraus had a musical foil in Jupp, aka folk-tronica artist Belbury Poly. ‘My role,’ says Jupp, ‘was to turn a live performance work, with no strict timings and cues, into an album. Starting from a rough guide track recorded on Justin’s phone, alongside Sharron’s early demos, we built a skeleton for the music and sound effects. This was gradually re-recorded in the studio.’

Kraus describes her writing process for the project as very instinctive: ‘Justin initially sent me the text and I felt the stirrings of my musical imagination. I recorded a handful of sound sketches and sent them to Justin who liked how they were going. By the time of the first performance we’d spent a day together, making sure the music sections fitted the text.’

The full dose of Chanctonbury Ringsinduces a kind of sacred tipsiness. As if freed from inhibition the listener feels active in this album’s rituals, not just observant. Hymnal synths, pagan piping and hushed chorals act like a series of mantras to highlight the narrative. Hopper venerates each word, his voice like an instrument itself ranging from breathy to bright. As the sonic atmospheres build, you sense a thickening of the world where fact and reason vanish.

Hopper’s prose is so evocative that any backing might seem surplus, but the soundtrack here is sensitive not invasive. American by birth, Hopper admits he gets choked up over the composition that’s named after his grandmother, Winnie, a key figure in his relationship to England. ‘Sharron really dug in and wrote this profound music to not just accompany my words, but to reinforce and reinterpret them’ he says.

‘Chanctonbury Rings (Intro)’ opens the record with Hopper’s enticing line, ‘Time had gone soft at the crossroads… and let me tell you how’. This heralds a synth swirl and tingle that’s almost apparitional, whilst elsewhere much fun lies in detecting the various implements used. Kraus explains there’s actually no guitar on the album, except for Nick Jonah Davis playing electric and slide on ‘Wanderer’. The hallowed chords on ‘Layers’ and ‘Wanderer’ come from an open-tuned dulcimer, wherein Kraus strikes the instrument’s body like someone rapping a coffin lid.

Ghostly exhales and buzzy drones on ‘Breath’ were created by Kraus layering bamboo flute, vocal noises and percussion, with Jupp adding extra elements. The close-mic’d crackling from a box of dried leaves adds a hair-raising creepiness. ‘Bonny Breast Knot’ then conjures an impish galliard that high steps into a full country dance. It’s one of several pieces to feature Kraus on recorder, an instrument she disliked playing at school, until early music helped her ‘fall in love with the recorder’s sweet woody tone. It sounds so birdlike. I mostly play an alto, but there’s some descant on the album too.’

Jupp describes the microKORG used by Kraus as a ‘wonderful and massively underrated little synth’. It conjures bestial riffs on ‘The Devil And St. Dunstan’ where Jupp adds Mellotron and tape echo feedback. ‘Outside The Ring’ has electronics and woodwind together, with Jupp’s input being a woozy degraded sample of a Mellotron bell. Jupp says this number follows a common theme in his work, where time seems out of joint and archaic notions are re-framed in a modern way. (He adds that this may be a dated modernism in itself).

Further insight into Jupp’s ethos comes on ‘Chanctonbury Rings (End Title)’. A piece of courtly pomp with triumphal notes, Jupp says he wanted to capture an instant sense of English pastoralism, with a slow rise and fall to echo the Downs landscape. ‘Hopefully it’s slightly sinister, but lilting into the joyful,’ he says. ‘But like a radio theme I wanted it to be anthemic and plain old catchy too.’

The drama closes with Kraus performing the festive song ‘Hal-an-Tow’ in traditional style, her voice aglow like a woodland spirit’s. The tune reflects a May morning ritual attended by Hopper, but like an outsider within Chanctonbury’s symbolic rings, he then departs quietly: ‘I slipped away – no one knew me, no one noticed me leave. I skipped down the hillside, along tapering tracks. And like that, the calendar had turned. It was summer.’

*

Chanctonbury Rings is out on Ghost Box on 21 June. You can order a copy here.