Notes on Roger Ackling’s Work: an edited extract from Ben Tufnell’s In Land: Writings around Land Art and its Legacies, published yesterday by Zero Books.

Weybourne, 1989

Sunlight on wood

13.2 x 5.5 x 1.9 cms

© Estate of Roger Ackling and Annely Juda Fine Art, London

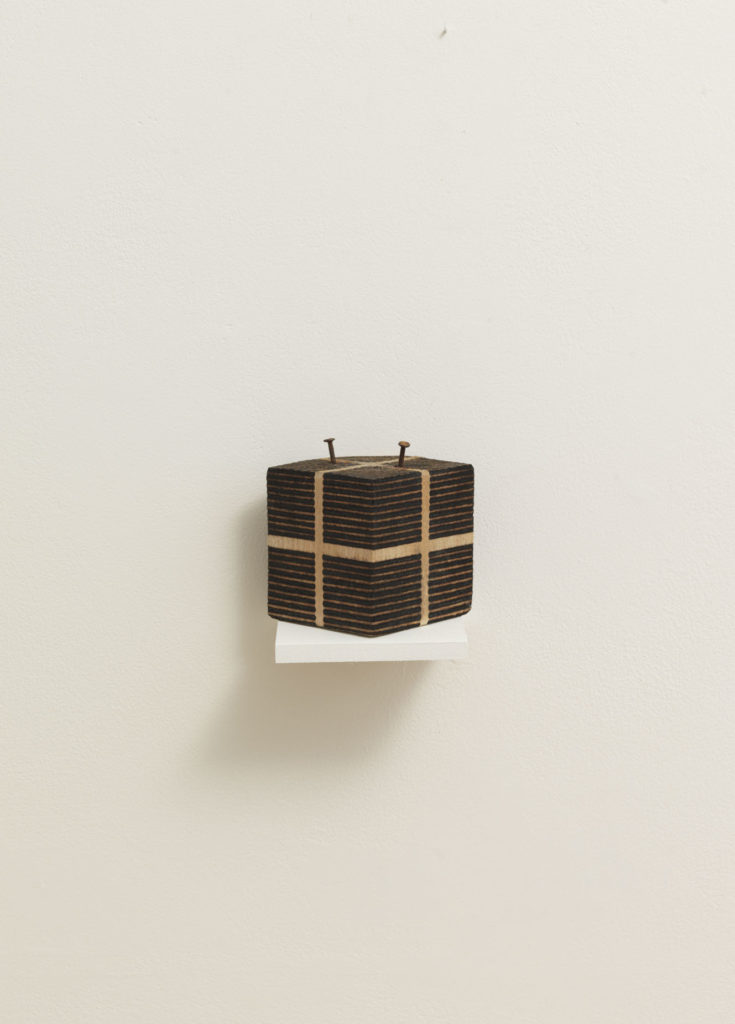

It is a small wooden object, small enough to be held in the palm of a hand. Its squarish shape denotes that it is, or was, man-made, but its angles have been beaten away by time and weather, smoothing out corners and edges. It is impossible to say what it might once have been, precisely, what its purpose or role was. Perhaps a piece of furniture, part of a boat, the remains of shed or crate, some kind of utensil. It is driftwood, evidently. Something given up by the sea. The head of a nail protrudes from one side, now rendered a deep burnt orange by the rust which stains the wood where the nail enters; again, the angles rounded away. The title, Weybourne, which is the name of a small village at the edge of the North Sea, tells us that this thing was gathered or made on the coast of Norfolk, a marginal place where land and sea are in a constant dance of entropic flux, where the cliffs crumble away a little bit more after every storm or high tide, where sand and shingle shift and move, and where the sea’s currents deposit flotsam and jetsam from places far away and unknown.

It has been changed by the journey that brought it to this present place. But something else has changed too. The surface of the wood has been marked with regular black lines, which on closer inspection are revealed to be scorch marks, carefully ordered burns, small dots of fire massed one by one to form lines. It has then been quite deliberately worked upon. It is a work by late Roger Ackling (1947-2014).

Ackling’s work is small scale, humble and modest. It is handheld and handmade and constitutes a form of private ritual, both in its making and, we might say, in its viewing. Ackling’s medium was light itself, or, to be more precise, sunlight. On a cloudy day he could not work.

Ackling’s work epitomises for me certain ideas about ‘Land Art’ as I understand it. While Ackling (like many of his artist friends) rejected such a label, his work has informed my thinking about an expanded notion of what something called ‘Land Art’ might be: an art made in, of, and about, a landscape, and being in a landscape. It is work that can only be made in a landscape – it simply cannot be made inside, in a studio – and it somehow seems to encode an aspect of being present in the landscape, even if what that is is only something as simple as being.

Voewood 2011

sunlight on wood

9.3 x 8.5 x 8.5 cm

© Estate of Roger Ackling and Annely Juda Fine Art, London

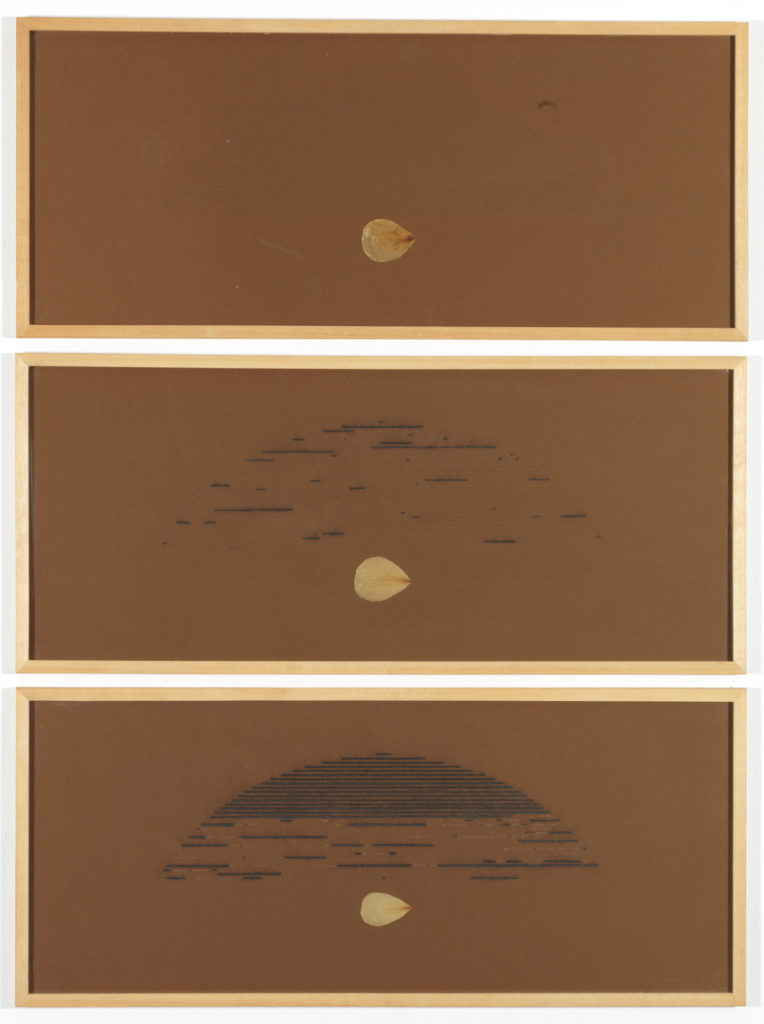

From the mid-1970s Ackling made his work on cardboard and old wooden crates, boxes and tools, but from about 1980, most characteristically, he used driftwood gathered on walking journeys or on the North Sea beaches near his home in Norfolk. Using a small lens he burnt the wood with sunlight, creating series of tiny dots or points, which formed lines, which in turn formed abstract motifs such as squares, grids or circles. Sometimes these seem to respond to the traces of use on the wood – bounding or isolating a rusted nail head or a patch of flaking paint, for example – and sometimes they appear to overwrite such marks. Ackling always worked from left to right, the lens held in his right hand, the sun over his right shoulder, as if writing. He described his process:

I’m watching a spot, a black spot on the surface of the wood. A rather over-exposed photograph of the sun. One dot joins up to the other one. One over-exposed photograph of the sun falls onto another one. That dot makes a line and that line makes a surface, and that surface makes my work.

This is disarmingly simple. The work is not intended to reveal anything other than the activity of the artist; it does not track cosmic events (although it does record the passage of time and the conditions of light during that passage). It is an art of small, repetitive acts, seemingly pointless and containing the thrilling possibility of meaninglessness. However, in making this work, Ackling is engaged in the moment, at one with his surroundings, sitting in the landscape, on a beach in Japan, the Outer Hebrides or in his garden in Norfolk. The form of the burns is planned in advance, so that he can empty his mind, ‘freeing it from any logical thought process so he can be wholly receptive to the air around him’.We might then understand his actions as a form of meditation, and that does feel about right. However, this was not Ackling’s own conception of his project:

People used to say to me ‘your work is some form of meditation’. Well, it’s not. I now let my mind do whatever it wants to do and the enjoyable thing is that it doesn’t want to do very much. Of course, one of the things that is often not discussed in relationship to landscape is that the outside world in some ways is an outer reflection of an inner state. When they come together seems an ideal moment.

Winter 1982

sunlight, pencil and petal on card, 3 part

23 x 54.5 cm each (9.06 x 21.46 in. each)

© Estate of Roger Ackling. Courtesy Annely Juda Fine Art, London

Through his intervention, time and place are encoded into the wooden objects with which he works. By means of the steady and painstaking pavement of the glass – which must surely entail Zen-like concentration and great stillness – a record of time and light is inscribed, and inner and outer realities are brought into alignment. Ackling once suggested that the smoke – the ephemeral product of the burn, quickly dispersed into the air –might actually be the work, which is a beautiful notion.

*

The debate around Roger Ackling’s work often revolves around a dialectic of meaning and meaninglessness. It is easy to say what the work is, how it was made, where it came from, but it is not so easy to say what it means. Meaning here seems elusive. Describing the physical qualities of the objects gets nowhere near the numinous aura of mystery that surrounds them. Something of place but also of the artist’s experience of enacting this ritualistic process, perhaps perched at the very edge of the ocean, seems to imbricate the resulting object. We know the process and can perhaps imagine Ackling at work, but it nonetheless remains remote. However, for this viewer, somewhere between the object and the process meaning does coalesce.

The work is a private ritual, at once seemingly empty and at the same time magically full and rich and moving. In his words:

rituals performed in private

change the face of the world.

At the same time, Ackling has asserted that, ‘I’m not sure I know what I’m doing. I’m not trying to communicate anything. I don’t have an objective.’ Nonetheless, ‘The quality of experience while making the work is important. I choose to make my work in silence and sitting still.’ Ackling then has it both ways, and strikes me as akin to the Zen master who asks the adept, what is the sound of one hand clapping? The paradox here, of course, is that in this context even meaninglessness is meaningful if it is deliberate. In silence and sitting still is perhaps the best way to consider this conundrum.

Voewood 2006

sunlight on wood with nails and paint

2 parts, each: 19.8 x 4.1 x 2.5 cm

© Estate of Roger Ackling. Courtesy Annely Juda Fine Art, London

And beyond this there is something else, something personal and perhaps, poetic. For me the idea of the artist at work, in his garden or on a beach, engaged in making what is essentially the same work over and over again, taking his modest and mundane materials and transforming them (without actually touching them), is profoundly moving. Somehow, knowing that Ackling’s work exists does change the world.

*

In Land: Writings around Land Art and its Legacies is out now and available here.

You can watch Ben Tufnell discussing the concept of Land Art here.