In Part 4 of her Alice Oswald-inspired walk along the Dart, Katherine Venn enjoys stained glass, a physic garden, a steam train, and a dip in the river

The miracle of next-day delivery works and after breakfast here are my shoes, with grateful thanks to my colleague Emily back in London. Even better, they fit, if snugly – I have to wear them barefoot, my wool socks far too thick for such lightweight beauties. I’m still pinching myself for my good luck, even if it’s good luck that’s mitigated against the bad. But my boots were ancient, and perhaps it was the soaking yesterday that finally did for them.

I’m back on the pub’s terrace, studying my map on one of the wooden tables that look out over the Dart, alive with little birds skimming the water. Much of the river isn’t public access at this point, but a steam train runs right next to it, so I decide that I won’t walk much today, despite now actually having the means to do so. Instead I head back into Buckfast and the Abbey.

I’m intrigued by the enclosed life of monasteries, and especially those in this country that have resolved themselves back into being after centuries of nothing. But (forgive me) this place feels a little too cleanly new, a little Disneyfied, and entirely too full of coach trips. I’m being unfair as well as a snob, of course: I too am a visitor, and I’m not Catholic. But there’s little by way of quiet and more than once I’m pushed out of someone’s way, and not by a child. The gardens are sweet to walk around but don’t have the rambling peace of other abbeys I’ve visited that are also home to religious communities. Wandering round the part of the physic garden where all the poisonous plants are safely kept away from fingers and mouths by a surrounding trench of water, I think fondly of my mum, and how, in the physic garden at Villandry on a family holiday over a decade ago, she startled everyone within hearing when she sharply called out ‘stop!’ as I reached to touch a plant that would have burned my skin.

I find the quiet that perhaps I was hoping for in the chapel of the Abbey church. One whole wall is an enormous stained-glass window: a modern representation of Christ, his arms out in welcome. At home I learn that the window is made with a technique called dalle de verre, which produces much more intense colours than traditional stained glass. There is no chatter, no bustle. A few people sit silently. I join them and sit in the glow of the stained glass for a while, allowing myself to be embraced by the colour, the deep deliberate hush, what the glass is portraying. Afterwards I realise it had reminded me of the modern stained glass of my grandparents’ evangelical church – ironically, at the opposite end of the spectrum to the tradition here – which I’d stare at during long services as a child.

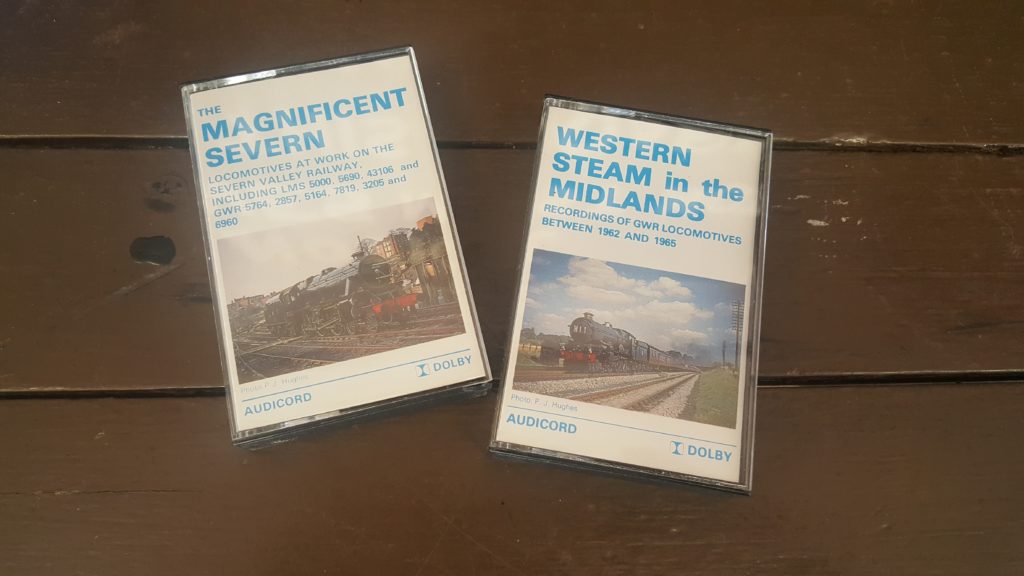

I leave the Abbey and head back down to Buckfastleigh where I pick up the steam train. This is the South Devon Railway, which runs the seven miles between here and Totnes. It’s not just the engine that’s vintage, but the rolling stock too: wooden floors and old-fashioned sliding windows. I tuck into a seat at a table by the window so that I’m right on the river, which we hug for one stop and twenty minutes, though it feels like five, till I get off at Staverton. The whole thing seems to be run by retired men, happy in their high-vis and station uniform. I have a sandwich in their parked-up buffet carriage and leave my rucksack in the stationmaster’s office to head down to the Dart for a swim.

I’ve been reading Dart slowly downstream, matching the places it mentions to my route, so that I’m reading just a page or two at a time. It’s the poem that alerts me to the fact that there’s a swimming spot here:

We jump from a tree into a pool, we change ourselves

into the fish dimension. Everybody swims here

under Still Pool Copse, on a Saturday,

slapping the water with bare hands, it’s fine once you’re in.(‘swimmer’)

Still Pool Copse is marked on my map so I cross the river, into a plantation wood and amble down to a spot that’s surprisingly busy with a few families and lots of kids, splashing down into the water from a rope swing: some confident, some needing to be persuaded. I wander around a bit to find somewhere to change before giving up and stripping off in the half-screen of a large tree, its leaves kissing the stones that hurt my feet, where a woman comes over to change too, along with her gorgeous black lab. We swim up the river together, talking about the pull of the water and leaving London.

He dives, he shuts himself in a deep soft-bottomed silence

which underwater is all nectarine, nacreous. He lifts

the lid and shuts and lifts the lid and shuts and the sky

jumps in and out of the world he loafs in.

Debbie lives close by and swims in the Dart most days. I’m envious. We dry off and I watch a gang of ducklings take the rapids past a little gravel island, then ford the river, knee high, holding up my dress, shoes in my hands, joining Debbie to walk back up to Staverton where I board the train again for the last stretch to Totnes Riverside.

It’s hot. The oaks reach out across the river. A group of kayaks are paddling upstream, waving to us. Bump bump of the train. And too soon we’re at Totnes Riverside where I’m reluctant to leave this time capsule of heritage nostalgia and the charming men selling ice creams and old copies of railway magazines. I’m also feeling restless: I’ve swum, but the lack of walking makes me itch, and I’ve got time to kill before meeting my cousin, who I’m staying with tonight. I wander downstream along the river, where I sit on a bench with an industrial estate behind me and a main road on the other side of the Dart in front, brown and turbid here.

All of a sudden I feel hemmed in by time and the tension between wanting to plan and wanting to drift, and what can and what can’t be done. I should have walked upstream, I fret, it would have been prettier. Motorbikes pop loudly, herring gulls call, cars swoosh, crows caw and I sit here making little insect noises with my pen on the page and the swoosh of my palm’s skin as it skooshes across the page too – like the scoosh swoosh of the beech leaves above as if they are trying to hush the wind.

Exhausted almost to a sitstill,

letting the watergnats gather, for I am no longer

able to walk except on a slope,I inch into the weir’s workplace,

pace volume light dayshift nightshift

water being spooled over, nowmy head is about to slide – furl up my eyes,

give in to the crash of

surrendering riverflesh falling …(‘the river meets the Sea at the foot of Totnes Weir’)

And then I walk to my cousin’s house, who I meet on the way with her daughters, and am wrapped back again in the company of people I know, who know me, including their cat who graces me with his heavy company on the sofa-bed.